Private Rights of Action in US Privacy Legislation

This article analyzes private rights of action in US state and federal privacy legislation.

Published: 10 June 2024

Additional Insights

The discussion draft of the American Privacy Rights Act has set the privacy community abuzz. At the heart of the draft is one of the most politically charged topics in privacy legislation: the inclusion of a private right of action. In the press release introducing the draft bipartisan, bicameral bill, U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Wash., and Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., were adamant that robust enforcement mechanisms that "give consumers the ability to enforce (privacy rights)" are necessary in a federal data privacy law. However, another stakeholder, Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, publicly wrote he "cannot support any data privacy bill that empowers trial lawyers" in a post on X. PRAs have a rich history in legislation and regulations. Although now considered more controversial, they have been employed in federal legislation in the U.S. for over a century. The more recent political debates concerning PRA inclusion in privacy, data and technology legislation sparked an uptick in research that seeks to examine their history and opine on their effectiveness. This article examines the enforcement provisions contained in the revised discussion draft of the APRA, as released 9 April.

What are PRAs?

Broadly, U.S. legislation is primarily focused on after-the-fact, or ex-post, enforcement. Compared to regulatory schemes that aim to regulate before a harm occurs, after-the-fact enforcement regulates by placing repercussions on a violator for failure to comply with an applicable law or regulation after a violation or harm occurs. The main enforcement mechanisms under this ex-post regulatory structure are public enforcement, private enforcement or a hybrid of both.

Public enforcement empowers governments or their agents to enforce violations of substantive laws. For example, a prosecutor may bring a criminal complaint on behalf of the state against a person for a violation of the criminal code. Private enforcement allows individuals to hold a violator responsible by imposing consequences for harms that the individual has suffered. These individuals are statutorily empowered to bring private lawsuits in specific jurisdictions for specified remedies to mitigate or cure the harms caused by violators. PRAs can be both implied or explicit depending on the language employed by the statute and the court's interpretations. PRAs can, therefore, spawn litigation by providing a direct avenue for harmed individuals to seek redress of their injuries.

Any statute that creates a PRA must define, at a minimum, the characteristics and categories of individuals that have standing to bring an action and what remedies are available. For example, the original text of the Communications Act of 1934 provides a PRA against common carriers who violate it, allowing an injured person to recover the full amount of their damages and their attorney fees. While some PRAs are intentionally broad to allow for the evolution of an industry, PRAs can also be narrow depending on how much private enforcement the legislature desires.

PRAs can be limited in scope to certain violations, such as smaller violations that may not be a priority of public enforcers, or conversely, restricted to only allowing actions against companies of a certain size with the ability and resources to defend the claims adequately. The statute could also clarify the factual findings required for certain remedies, the burden of proof, who the fact finder is, if a specific party bears the cost of litigation and other procedural aspects impacting the amount of litigation that would feasibly result from the right. In nearly every legislation with a hybrid enforcement structure, the recovery of damages from a public enforcement action is deducted from a private action brought for the same offense.

In the context of antitrust laws, the U.S. Supreme Court commented in dicta that including a PRA as an enforcement mechanism "was not merely to provide private relief, but was to serve as well the high purpose of enforcing the antitrust laws." Political administrative conflicts and the privatizing of enforcement costs are just two of the many reasons why only 3% of lawsuits enforcing federal laws were prosecuted by the federal government.

The controversy

Many in favor of PRA provisions in privacy legislation argue that the inherently personal nature of privacy rights to consumers lends itself to PRAs. Because privacy rights are so entwined with one's dignity, an avenue for an individual to contest privacy violations personally is a recognition of a privacy right. Additionally, harmed individuals are uniquely situated as the most likely to discover a violation has occurred and are similarly motivated to seek redress for the consequences of that violation.

Some argue the current American administrative state cannot manage the potential magnitude of privacy enforcement without the aid of private enforcement models. Agency funding, capacity or even political will could change and leave individuals harmed by violations without an avenue for recourse. Even with full funding and staffing, public agencies like the Federal Trade Commission cannot and do not take action against every violator but rather seek to set norms and encourage every actor to improve compliance with the most effective number of actions. This means under a hybrid model, private actions would supplement public enforcement, allowing public agencies to devote more time and resources to large-scale issues.

Meanwhile, private enforcement actions would provide ongoing incentives for companies to comply with relevant laws in every interaction with every consumer, not just the ones a public entity elects to prioritize or enforce. PRAs allow enforcement in a manner that avoids blame on an administration for an unpopular decision, whether they decide to prosecute or not. The private bar also has a history of establishing precedents through novel arguments and legal theory that enforcement agencies can then adopt and utilize. Proponents of PRAs emphasize that even unsuccessful claims by individuals can draw a public agency's attention to industry problems and the discovery process can unearth corporate misconduct.

Opponents of PRAs in privacy legislation have just as encompassing arguments. Some believe private lawsuits lead to excessive and inefficiently high levels of enforcement for violations, wasting the resources of both the court systems and the alleged violators. The argument assumes individuals may not have the public interest in mind when choosing how to resolve their own privacy violations, preferring to seek a resolution that only benefits them and ignores a larger good or business activities that are good for society. Private lawsuits and the resulting monetary settlements or damages take away funds that could be used to promote better practices and benefit more than one individual. Additionally, settlements, which are how many legal actions are resolved, usually require nondisclosure agreements that inhibit the transparency of bad conduct or behavior rather than promoting transparency to deter future wrongful conduct. Still, others see PRAs as benefiting only plaintiff attorneys, who can be incentivized to pursue unworthy claims to generate more business for themselves.

Yet others suggest a fundamental function of government is the state's responsibility to ensure compliance with enacted legislation and regulation on behalf of individuals. A government agent, including those governed at its highest level in a bipartisan capacity, is uniquely situated to respond to the priorities of the public. Legal actions are expensive, and leaving enforcement areas to individuals may result in no enforcement in areas that affect people who cannot pay legal costs.

PRAs in federal legislation

Balances and compromises have been found many times by different Congresses and by various administrations. The following sections explore enacted and proposed legislation that employ PRAs as an enforcement mechanism across industries.

Enacted legislation

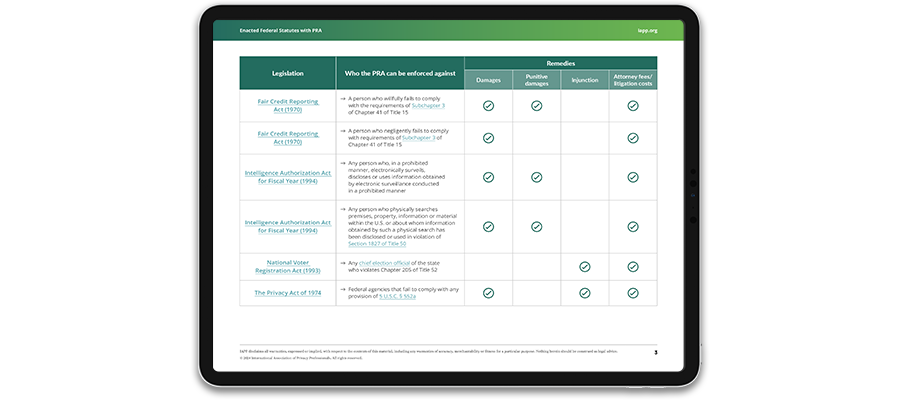

As already stated, PRAs have been employed by Congress for over a century in many areas of law. The following chart depicts enacted legislation in the areas of privacy, data, digital, technology and telecommunications that explicitly create PRAs as an enforcement mechanism, as well as their scopes and available remedies.

Chart: Enacted Federal Statutes with PRA

(Click to view as PDF)

Proposed federal legislation

PRAs remain a feature in many proposed federal privacy bills, and continue to be one of the most divisive provisions in the current federal privacy law debate. Although typically found in bills sponsored by Democrats, PRAs are not limited to bills sponsored by one party. Republican and bipartisan bills across nearly every category of law have sought to utilize private enforcement mechanisms. For instance, in 2022, Sens. Mike Lee, R-Utah, Ted Cruz, R-Texas, Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., and Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., introduced the Competition and Transparency in Digital Advertising Act, which would have provided a private right of action for individuals against violators of its requirements, including transparency, retention limits and user privacy. Recovery would have been available against violators with more than USD20 billion in digital advertising revenue in a calendar year, although in some circumstances prevailing plaintiffs would recover damages of either USD1 million for every month in which a violation occurred or actual damages, whichever was greater, plus attorney fees. This bill was later co-sponsored by Sens. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., Steve Danies, R-Mont., and Josh Hawley, R-Mo., but never advanced out of committee.

State privacy laws and PRAs

PRAs are hotly debated at the state level during the drafting and hearing process for state comprehensive privacy laws. In Washington state, efforts to pass comprehensive privacy legislation failed during multiple sessions with the most divisive issue being the inclusion of a private right for enforcement. Extensive compromises were sought to persuade House Speaker Laurie Jinkins, D-Wash., a staunch supporter of the inclusion of PRA provisions, to even allow a bill to be heard on the House floor.

Following those failed efforts, in 2023, Washington state's My Health My Data Act was signed into law. The law aims to provide data privacy protections for health data that falls outside the scope of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in a consent-driven manner and includes incredibly broad definitions of data. Section 11 of the MHMDA makes a violation of the act enforceable under the state's consumer protection laws, which includes a PRA for consumers. Additionally, it establishes a joint committee to review enforcement actions brought under the act within the first few years, measure the legislation's impact, author a report on the impact and effectiveness of the hybrid provisions and make recommendations for potential changes to existing enforcement provisions by September 2030. The joint committee's report and recommendations could be insightful for the survival of the MHMDA's PRA if the law is not preempted.

Similar to Washington state's effort to pass comprehensive privacy legislation, in 2021 the proposed Florida Privacy Protection Act failed despite the near unanimous support of the Florida House and Gov. Ron DeSantis. The original bill proposed a broad and comprehensive privacy law that would require companies conducting business in Florida and making USD50 million annually to disclose what personal information they collect and how it is used, in addition to consumer rights such as correction, opt outs and deletion. The private enforcement provision of the Republican-sponsored bill was removed by the Senate's amendment, and the dispute about the inclusion of the PRA desired by DeSantis and the Florida House was identified as the key provision that led to a stalemate.

Since that attempt, Florida enacted a Digital Bill of Rights, which affords new privacy rights to Florida residents by codifying fair information practice principles and requirements on businesses, albeit applying those rights and requirements to narrowly defined controllers. Unlike Washington's MHMDA, Florida's Digital Bill of Rights explicitly excluded the once mandatory PRA and instead designated enforcement to the attorney general.

As of the date of publishing, California still serves as the only example of enacted U.S. comprehensive privacy legislation that employs PRAs, though Vermont is on the verge of joining it. The California Consumer Privacy Act and California Privacy Rights Act both employ a hybrid enforcement model with PRAs limited to data breaches. The CCPA provided a PRA to consumers whose nonencrypted or nonredacted personal information is subject to data breaches as a result of a business's violation of their "duty to implement and maintain reasonable security procedures and practices." The CPRA added additional categories of personal information, such as email addresses in combination with a password or security question and answer that would permit access to the consumer's account, to the list of actionable data types under the law in the event of a breach. Although California is the only state to have enacted a comprehensive law containing PRAs, another attempt on the federal level is awaiting introduction to Congress.

The APRA and the ADPPA: a PRA comparison

The discussion draft of the APRA employs a hybrid enforcement mechanism of public enforcement through the FTC and state officers, as well as a PRA for individuals harmed by certain violations. In addition to government actors, individuals may bring a civil action against an entity for specific violations concerning:

- Sensitive covered data.

- Biometric and genetic information.

- Transparency for material changes.

- Individual control of covered data.

- Consent and opt-out mechanisms.

- Interference with or retaliation for exercising consumer rights.

- Denial of services or providing different levels or quality of services.

- Data security practices.

- Due diligence in service provider selection and decisions to transfer covered data to third parties.

- Data broker registrations.

- Civil rights.

- Opt-out rights for consequential decisions made by covered algorithms.

The relief available to successful plaintiffs in any action under the APRA is the sum of actual damages, injunctive relief, including a court order that the entity retrieve any covered data shared in violation of the act, declaratory relief, and reasonable attorney fees and litigation costs. Additional relief is available if a violation involving biometric data or genetic information occurred in Illinois, or if California residents bring claims alleging a data breach arose from violations of an entity's obligations of data security practices.

Any damages awarded to an individual are offset by damages received from an action against the same entity for the same violation brought by a public enforcement agency. The current APRA also includes procedural notice requirements and a time frame in which an entity may cure the harm before a complaint can be filed unless the violation resulted in a substantial privacy harm.

Prior to the APRA, the most recent comprehensive federal privacy legislation was the proposed American Data Privacy and Protection Act in 2022. While the drafts of the ADPPA and APRA both include hybrid enforcement models, their PRA provisions are distinct from each other, especially in terms of scope. The 20 July 2022 ADPPA draft out of the Energy and Commerce Committee applied broadly to organizations operating in the U.S., imposed different requirements and exemptions depending on their size and processing capacity, and prescribed substantive requirements that differed depending on the role of an entity with covered data. It also provided a right of action to any person or class of persons for violations under the ADPPA or a regulation promulgated thereunder. The ADPPA's PRA would not have come into effect until two years after the effective date of the bill, compared with six months in the current APRA draft.

More work to do

The still unintroduced APRA is at the first of many hurdles it must clear before it reaches enactment. Future discussions and hearings in Congress will undoubtably focus on the inclusion and scope of a contentious PRA provision in addition to other amendments. The only certainty from this juncture is that if a PRA does form part of a future federal privacy legislation, it will be one of many important features that will drive compliance in conjunction with public enforcement. The IAPP will closely track PRA inclusion, as well as all other updates, in the APRA amendments and other privacy bills to come.

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Private Rights of Action in US Privacy Legislation

This article analyzes private rights of action in US state and federal privacy legislation.

Published: 10 June 2024

Contributors:

Cheryl Saniuk-Heinig

CIPP/E, CIPP/US, CIPM

Former research and insights analyst, IAPP

Additional Insights

The discussion draft of the American Privacy Rights Act has set the privacy community abuzz. At the heart of the draft is one of the most politically charged topics in privacy legislation: the inclusion of a private right of action. In the press release introducing the draft bipartisan, bicameral bill, U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Wash., and Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., were adamant that robust enforcement mechanisms that "give consumers the ability to enforce (privacy rights)" are necessary in a federal data privacy law. However, another stakeholder, Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, publicly wrote he "cannot support any data privacy bill that empowers trial lawyers" in a post on X. PRAs have a rich history in legislation and regulations. Although now considered more controversial, they have been employed in federal legislation in the U.S. for over a century. The more recent political debates concerning PRA inclusion in privacy, data and technology legislation sparked an uptick in research that seeks to examine their history and opine on their effectiveness. This article examines the enforcement provisions contained in the revised discussion draft of the APRA, as released 9 April.

What are PRAs?

Broadly, U.S. legislation is primarily focused on after-the-fact, or ex-post, enforcement. Compared to regulatory schemes that aim to regulate before a harm occurs, after-the-fact enforcement regulates by placing repercussions on a violator for failure to comply with an applicable law or regulation after a violation or harm occurs. The main enforcement mechanisms under this ex-post regulatory structure are public enforcement, private enforcement or a hybrid of both.

Public enforcement empowers governments or their agents to enforce violations of substantive laws. For example, a prosecutor may bring a criminal complaint on behalf of the state against a person for a violation of the criminal code. Private enforcement allows individuals to hold a violator responsible by imposing consequences for harms that the individual has suffered. These individuals are statutorily empowered to bring private lawsuits in specific jurisdictions for specified remedies to mitigate or cure the harms caused by violators. PRAs can be both implied or explicit depending on the language employed by the statute and the court's interpretations. PRAs can, therefore, spawn litigation by providing a direct avenue for harmed individuals to seek redress of their injuries.

Any statute that creates a PRA must define, at a minimum, the characteristics and categories of individuals that have standing to bring an action and what remedies are available. For example, the original text of the Communications Act of 1934 provides a PRA against common carriers who violate it, allowing an injured person to recover the full amount of their damages and their attorney fees. While some PRAs are intentionally broad to allow for the evolution of an industry, PRAs can also be narrow depending on how much private enforcement the legislature desires.

PRAs can be limited in scope to certain violations, such as smaller violations that may not be a priority of public enforcers, or conversely, restricted to only allowing actions against companies of a certain size with the ability and resources to defend the claims adequately. The statute could also clarify the factual findings required for certain remedies, the burden of proof, who the fact finder is, if a specific party bears the cost of litigation and other procedural aspects impacting the amount of litigation that would feasibly result from the right. In nearly every legislation with a hybrid enforcement structure, the recovery of damages from a public enforcement action is deducted from a private action brought for the same offense.

In the context of antitrust laws, the U.S. Supreme Court commented in dicta that including a PRA as an enforcement mechanism "was not merely to provide private relief, but was to serve as well the high purpose of enforcing the antitrust laws." Political administrative conflicts and the privatizing of enforcement costs are just two of the many reasons why only 3% of lawsuits enforcing federal laws were prosecuted by the federal government.

The controversy

Many in favor of PRA provisions in privacy legislation argue that the inherently personal nature of privacy rights to consumers lends itself to PRAs. Because privacy rights are so entwined with one's dignity, an avenue for an individual to contest privacy violations personally is a recognition of a privacy right. Additionally, harmed individuals are uniquely situated as the most likely to discover a violation has occurred and are similarly motivated to seek redress for the consequences of that violation.

Some argue the current American administrative state cannot manage the potential magnitude of privacy enforcement without the aid of private enforcement models. Agency funding, capacity or even political will could change and leave individuals harmed by violations without an avenue for recourse. Even with full funding and staffing, public agencies like the Federal Trade Commission cannot and do not take action against every violator but rather seek to set norms and encourage every actor to improve compliance with the most effective number of actions. This means under a hybrid model, private actions would supplement public enforcement, allowing public agencies to devote more time and resources to large-scale issues.

Meanwhile, private enforcement actions would provide ongoing incentives for companies to comply with relevant laws in every interaction with every consumer, not just the ones a public entity elects to prioritize or enforce. PRAs allow enforcement in a manner that avoids blame on an administration for an unpopular decision, whether they decide to prosecute or not. The private bar also has a history of establishing precedents through novel arguments and legal theory that enforcement agencies can then adopt and utilize. Proponents of PRAs emphasize that even unsuccessful claims by individuals can draw a public agency's attention to industry problems and the discovery process can unearth corporate misconduct.

Opponents of PRAs in privacy legislation have just as encompassing arguments. Some believe private lawsuits lead to excessive and inefficiently high levels of enforcement for violations, wasting the resources of both the court systems and the alleged violators. The argument assumes individuals may not have the public interest in mind when choosing how to resolve their own privacy violations, preferring to seek a resolution that only benefits them and ignores a larger good or business activities that are good for society. Private lawsuits and the resulting monetary settlements or damages take away funds that could be used to promote better practices and benefit more than one individual. Additionally, settlements, which are how many legal actions are resolved, usually require nondisclosure agreements that inhibit the transparency of bad conduct or behavior rather than promoting transparency to deter future wrongful conduct. Still, others see PRAs as benefiting only plaintiff attorneys, who can be incentivized to pursue unworthy claims to generate more business for themselves.

Yet others suggest a fundamental function of government is the state's responsibility to ensure compliance with enacted legislation and regulation on behalf of individuals. A government agent, including those governed at its highest level in a bipartisan capacity, is uniquely situated to respond to the priorities of the public. Legal actions are expensive, and leaving enforcement areas to individuals may result in no enforcement in areas that affect people who cannot pay legal costs.

PRAs in federal legislation

Balances and compromises have been found many times by different Congresses and by various administrations. The following sections explore enacted and proposed legislation that employ PRAs as an enforcement mechanism across industries.

Enacted legislation

As already stated, PRAs have been employed by Congress for over a century in many areas of law. The following chart depicts enacted legislation in the areas of privacy, data, digital, technology and telecommunications that explicitly create PRAs as an enforcement mechanism, as well as their scopes and available remedies.

Chart: Enacted Federal Statutes with PRA

(Click to view as PDF)

Proposed federal legislation

PRAs remain a feature in many proposed federal privacy bills, and continue to be one of the most divisive provisions in the current federal privacy law debate. Although typically found in bills sponsored by Democrats, PRAs are not limited to bills sponsored by one party. Republican and bipartisan bills across nearly every category of law have sought to utilize private enforcement mechanisms. For instance, in 2022, Sens. Mike Lee, R-Utah, Ted Cruz, R-Texas, Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., and Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., introduced the Competition and Transparency in Digital Advertising Act, which would have provided a private right of action for individuals against violators of its requirements, including transparency, retention limits and user privacy. Recovery would have been available against violators with more than USD20 billion in digital advertising revenue in a calendar year, although in some circumstances prevailing plaintiffs would recover damages of either USD1 million for every month in which a violation occurred or actual damages, whichever was greater, plus attorney fees. This bill was later co-sponsored by Sens. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., Steve Danies, R-Mont., and Josh Hawley, R-Mo., but never advanced out of committee.

State privacy laws and PRAs

PRAs are hotly debated at the state level during the drafting and hearing process for state comprehensive privacy laws. In Washington state, efforts to pass comprehensive privacy legislation failed during multiple sessions with the most divisive issue being the inclusion of a private right for enforcement. Extensive compromises were sought to persuade House Speaker Laurie Jinkins, D-Wash., a staunch supporter of the inclusion of PRA provisions, to even allow a bill to be heard on the House floor.

Following those failed efforts, in 2023, Washington state's My Health My Data Act was signed into law. The law aims to provide data privacy protections for health data that falls outside the scope of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act in a consent-driven manner and includes incredibly broad definitions of data. Section 11 of the MHMDA makes a violation of the act enforceable under the state's consumer protection laws, which includes a PRA for consumers. Additionally, it establishes a joint committee to review enforcement actions brought under the act within the first few years, measure the legislation's impact, author a report on the impact and effectiveness of the hybrid provisions and make recommendations for potential changes to existing enforcement provisions by September 2030. The joint committee's report and recommendations could be insightful for the survival of the MHMDA's PRA if the law is not preempted.

Similar to Washington state's effort to pass comprehensive privacy legislation, in 2021 the proposed Florida Privacy Protection Act failed despite the near unanimous support of the Florida House and Gov. Ron DeSantis. The original bill proposed a broad and comprehensive privacy law that would require companies conducting business in Florida and making USD50 million annually to disclose what personal information they collect and how it is used, in addition to consumer rights such as correction, opt outs and deletion. The private enforcement provision of the Republican-sponsored bill was removed by the Senate's amendment, and the dispute about the inclusion of the PRA desired by DeSantis and the Florida House was identified as the key provision that led to a stalemate.

Since that attempt, Florida enacted a Digital Bill of Rights, which affords new privacy rights to Florida residents by codifying fair information practice principles and requirements on businesses, albeit applying those rights and requirements to narrowly defined controllers. Unlike Washington's MHMDA, Florida's Digital Bill of Rights explicitly excluded the once mandatory PRA and instead designated enforcement to the attorney general.

As of the date of publishing, California still serves as the only example of enacted U.S. comprehensive privacy legislation that employs PRAs, though Vermont is on the verge of joining it. The California Consumer Privacy Act and California Privacy Rights Act both employ a hybrid enforcement model with PRAs limited to data breaches. The CCPA provided a PRA to consumers whose nonencrypted or nonredacted personal information is subject to data breaches as a result of a business's violation of their "duty to implement and maintain reasonable security procedures and practices." The CPRA added additional categories of personal information, such as email addresses in combination with a password or security question and answer that would permit access to the consumer's account, to the list of actionable data types under the law in the event of a breach. Although California is the only state to have enacted a comprehensive law containing PRAs, another attempt on the federal level is awaiting introduction to Congress.

The APRA and the ADPPA: a PRA comparison

The discussion draft of the APRA employs a hybrid enforcement mechanism of public enforcement through the FTC and state officers, as well as a PRA for individuals harmed by certain violations. In addition to government actors, individuals may bring a civil action against an entity for specific violations concerning:

- Sensitive covered data.

- Biometric and genetic information.

- Transparency for material changes.

- Individual control of covered data.

- Consent and opt-out mechanisms.

- Interference with or retaliation for exercising consumer rights.

- Denial of services or providing different levels or quality of services.

- Data security practices.

- Due diligence in service provider selection and decisions to transfer covered data to third parties.

- Data broker registrations.

- Civil rights.

- Opt-out rights for consequential decisions made by covered algorithms.

The relief available to successful plaintiffs in any action under the APRA is the sum of actual damages, injunctive relief, including a court order that the entity retrieve any covered data shared in violation of the act, declaratory relief, and reasonable attorney fees and litigation costs. Additional relief is available if a violation involving biometric data or genetic information occurred in Illinois, or if California residents bring claims alleging a data breach arose from violations of an entity's obligations of data security practices.

Any damages awarded to an individual are offset by damages received from an action against the same entity for the same violation brought by a public enforcement agency. The current APRA also includes procedural notice requirements and a time frame in which an entity may cure the harm before a complaint can be filed unless the violation resulted in a substantial privacy harm.

Prior to the APRA, the most recent comprehensive federal privacy legislation was the proposed American Data Privacy and Protection Act in 2022. While the drafts of the ADPPA and APRA both include hybrid enforcement models, their PRA provisions are distinct from each other, especially in terms of scope. The 20 July 2022 ADPPA draft out of the Energy and Commerce Committee applied broadly to organizations operating in the U.S., imposed different requirements and exemptions depending on their size and processing capacity, and prescribed substantive requirements that differed depending on the role of an entity with covered data. It also provided a right of action to any person or class of persons for violations under the ADPPA or a regulation promulgated thereunder. The ADPPA's PRA would not have come into effect until two years after the effective date of the bill, compared with six months in the current APRA draft.

More work to do

The still unintroduced APRA is at the first of many hurdles it must clear before it reaches enactment. Future discussions and hearings in Congress will undoubtably focus on the inclusion and scope of a contentious PRA provision in addition to other amendments. The only certainty from this juncture is that if a PRA does form part of a future federal privacy legislation, it will be one of many important features that will drive compliance in conjunction with public enforcement. The IAPP will closely track PRA inclusion, as well as all other updates, in the APRA amendments and other privacy bills to come.

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Tags: