Brexit — love it or hate it, there is a significant chance it will happen.

If the United Kingdom leaves the European Union without a deal Nov. 1, it will automatically cease to be a member of the EU. U.K.-based companies will no longer be regulated under the EU General Data Protection Regulation Article 3(1), and U.K.-based individuals will no longer benefit from the protections offered to EU-based individuals by the GDPR.

However, as with most Brexit issues, that isn’t even half the story. The U.K. has already incorporated the GDPR directly into their own laws in the Data Protection Act 2018, so GDPR-equivalent regulation — the “U.K. GDPR” — exists in the U.K., which is largely identical to the EU, although the debate continues as to the extent these laws will diverge as court decisions in each jurisdiction are reached; neither of which will be considered binding precedent for the other. This law will change with the U.K.’s departure from the EU by The Data Protection, Privacy and Electronic Communications (Amendment etc.) (EU Exit) Regulations 2019, and references in the U.K. GDPR will change from the EU to the U.K. so that the law applies in an enforceable and U.K.-relevant manner.

The two most significant effects of this are that data transfers between the U.K. and the EU will be affected, and companies may need to appoint an extra EU representative.

There is plenty of material on the first point, for which the biggest issue is that while the U.K. will declare the EU “adequate” on day one, the EU will require the U.K. to enter into the full adequacy process in order for this to be reciprocal; meaning, U.K. personal data can flow to the EU unhindered under Article 45, but EU data flowing to the U.K. will require appropriate safeguards in line with Article 46. I will focus here on the second point, about the effect on the representative obligation.

The representative obligation — now and post-Brexit

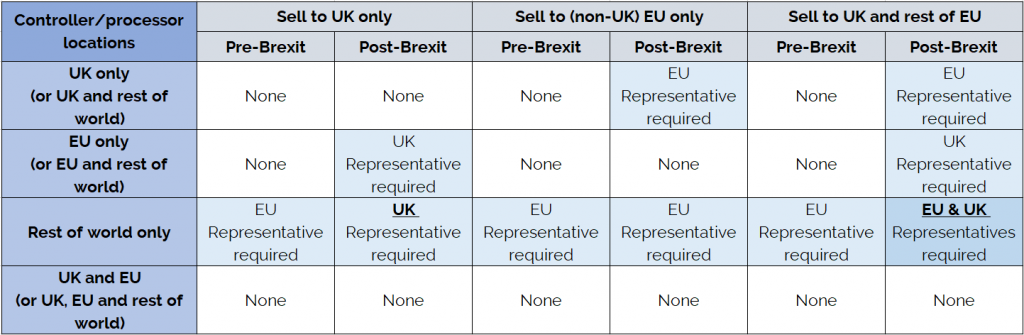

A quick refresher: Under GDPR Article 27, an EU representative must be appointed by a company (data controller or data processor) without an EU establishment if they sell to the EU or monitor people there. You can see more detail in my previous article.

Under the U.K. GDPR, there will also be an obligation to appoint a U.K. representative if a company without a U.K. establishment sells to the U.K. or monitors businesses there. The result is that companies without an office in either the EU or the U.K. will need to appoint both; they should already have an EU representative but, unless that representative has an establishment in the U.K., they will now need to seek out an additional provider to act in this role. U.K.-based companies selling into the EU without an EU office will need to appoint an EU representative, and vice versa.

Also, there are the non-European-headquartered companies that haven’t had the need for a representative until now because of a single EU outpost. Depending on the locations of their data subjects, they may find that — if their only EU office is in the U.K. — they will need to appoint an EU representative now, and likewise they may need a U.K. representative if their EU office(s) is not in the U.K.

A summary of the position now and post-Brexit is set out in the table below:

What should a data controller or processor do?

Knowing that Brexit is probably coming, but not being 100% certain, means that planning is difficult. This is unfortunately the case with all matters Brexit-related, and there remains a significant lack of clarity as to what will happen, if anything. As I prepare this article in early September 2019, the U.K. government has lost its majority in Parliament, meaning that a general election looks likely, although far from certain. The process of undertaking such an election would likely prevent any meaningful executive/legislative action until very close to the Brexit deadline. The default position under U.K. law is that the U.K. will leave the EU Nov. 1, whether a deal has been agreed or not — although opponents of a no-deal Brexit are seeking to change that default.

Matters on the EU side are no clearer: They do not want this to drag on any longer as it is taking up a large portion of their capacity (as well as providing fuel to EU opponents in other countries), but the financial damage forecast for many EU nations in the event of a no-deal Brexit means that they may be willing to provide another extension, kicking the can down the road a little longer, if they are asked by the U.K. and they believe that there is a chance that the delay would result in a deal. For context, prior to the previous extension, I had been telling people that there was no way an extension would be granted; I have since given up predicting anything Brexit-related!

If there is an extension or a deal is agreed between the U.K. and EU, the changing requirements mentioned above will not happen, at least not immediately; the originally proposed transition period in the current draft of the deal would run until the end of 2020, during which time the EU GDPR would continue to apply in the U.K.

I’d therefore suggest considering the following elements when planning to appoint an EU or U.K. representative:

- Can you agree to a conditional contract with them so there will be nothing to pay if Brexit doesn’t occur, the appointment is delayed during any extension period, or a deal is agreed between the EU and U.K. (a “No Brexit, No Fee” contract)?

- Will you need to appoint more than one representative (U.K. and EU) if you don’t currently have one? Alternately, can you appoint a representative with establishments in both jurisdictions?

- If you already have an EU representative, do they have a U.K. establishment? If so, will the U.K. representative role be automatically included with their existing appointment?

- The usual considerations for the appointment of an EU representative:

- Are they established in the EU member state where the controller/processor has the largest number of data subjects (a best-practice expectation set out in European Data Protection Board guidance note 03/2018, section 4)?

- Will data subjects in other EU member states have easy access to the representative (also set out in the guidance)?

- Is the representative already acting as your data protection officer (please be aware that, in line with the guidance, this is not permitted due to the potential conflict of interest between the roles)?

- How responsive are they, i.e. do they have a service level for acknowledging and forwarding communications they receive to ensure you have the maximum remaining time in the one-month timetable to respond to the request?

- Have they protected themselves against the risk of being required to pay GDPR fines and compensation awarded against their other clients, something that the EU authorities can ask the representative to do (if their client has not met those payments)?

There are more twists and turns to come before Brexit is done and dusted — until then, all anyone can do is prepare and hope for the best.

Photo by King's Church International on Unsplash

![Default Article Featured Image_laptop-newspaper-global-article-090623[95].jpg](https://images.contentstack.io/v3/assets/bltd4dd5b2d705252bc/blt61f52659e86e1227/64ff207a8606a815d1c86182/laptop-newspaper-global-article-090623[95].jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=pjpg&auto=webp)