Retrospective: 2024 in comprehensive state data privacy law

Published:

Contributors:

Keir Lamont

CIPP/US

Senior Director

Future of Privacy Forum

David Stauss

CIPP/E, CIPP/US, CIPT, FIP

Partner

Troutman Pepper Locke

Editor's note: This article is one of a two-part series exploring the state data privacy and sectoral laws and AI bills in the 2024 U.S. state legislative session. The authors also discussed the year in state privacy with IAPP Editorial Director Jedidiah Bracy.

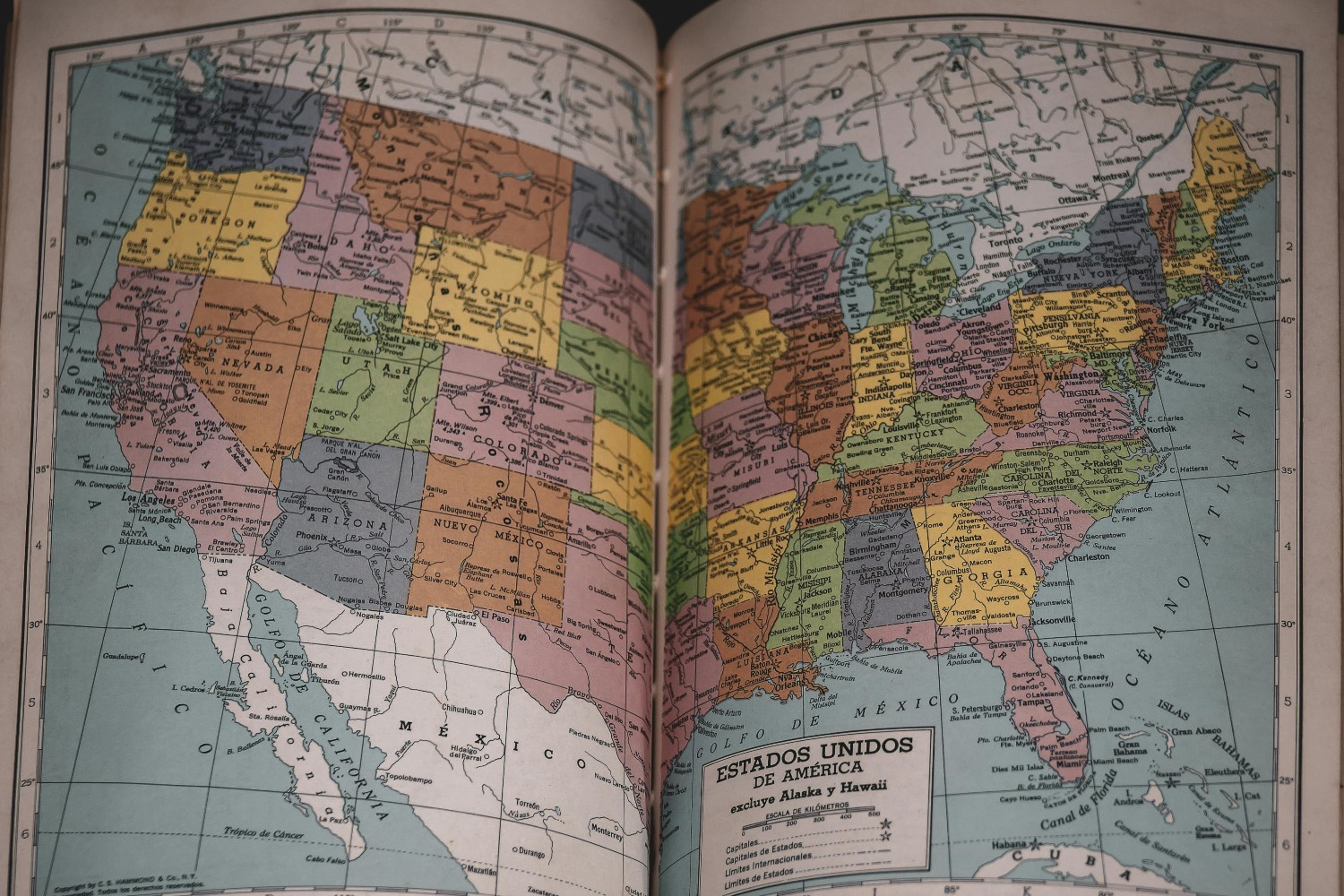

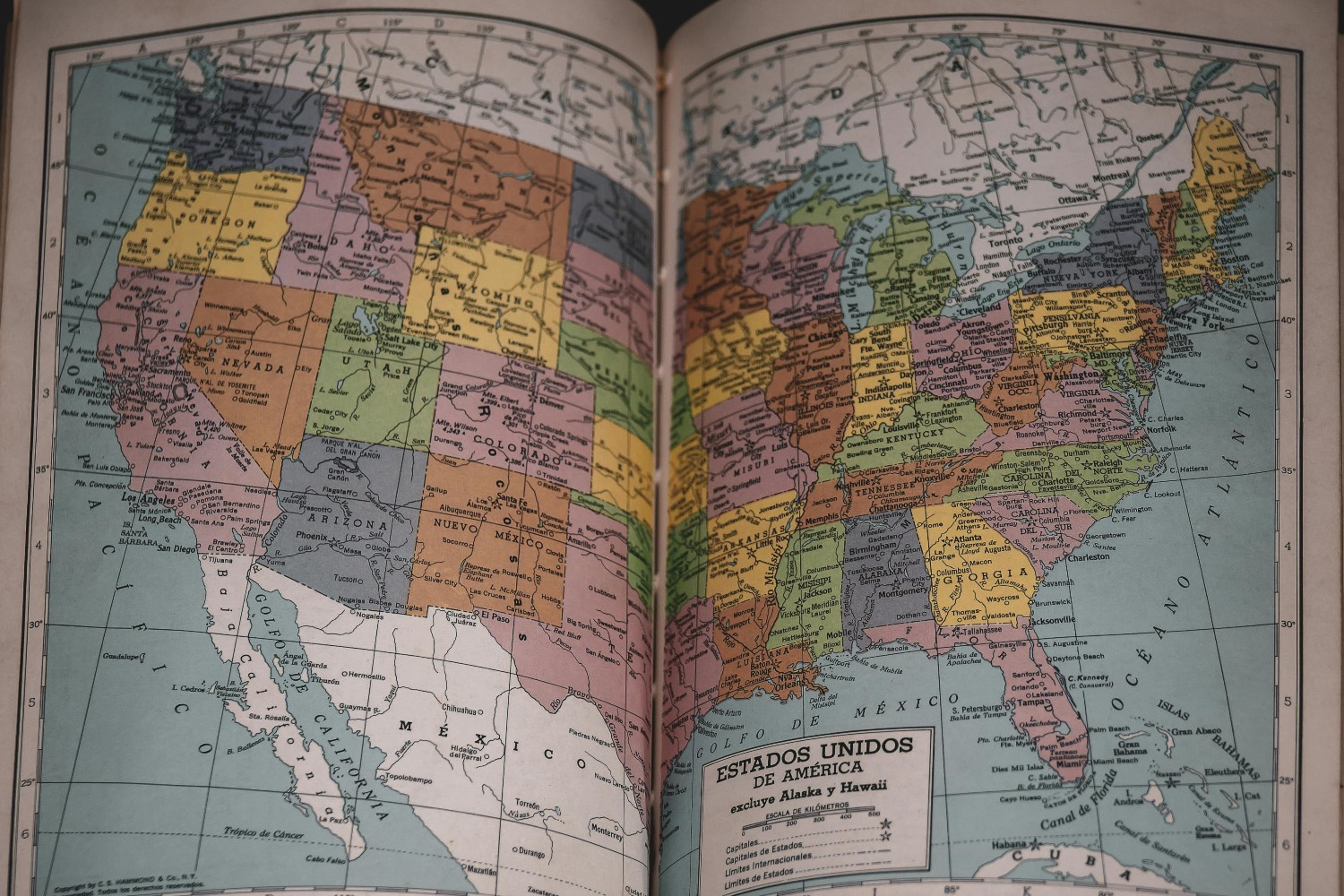

By the numbers, 2024 experienced a comparable level of activity to 2023 with seven new states passing comprehensive privacy laws, bringing the total number of state laws to 19 — or 20 depending on whether you count the controversial Florida Digital Bill of Rights.

However, 2024 saw much more variation in the data privacy bills considered and passed than prior years. Several states that adopted or came close to enacting privacy legislation did so with bills that differed significantly from the influential — though never enacted — Washington State Privacy Act, which served as the foundation for state data privacy laws enacted between 2021 and 2023.

In short, privacy professionals may come to look back on 2024 as marking the end of the "Pax-Washingtonia" era for U.S. state data privacy law.

A paradigm shift? Maryland, Vermont and Maine

Perhaps the most notable developments in state data privacy law this year came as Maryland finally enacted a state data privacy law, and Vermont and Maine failed to enact their bills.

Maryland's long road to enacting a state data privacy law is a microcosm for the development of state data privacy laws in the past few years. At least as far back as 2020, Maryland lawmakers were running on data privacy bills.

However, the 2020 bill focused on allowing Maryland residents to opt out of certain types of personal data transfers and stopped far short of the type of comprehensive bills states now routinely pass. Maryland lawmakers returned in 2021, 2022 and 2023 with bills that continually grew broader and more restrictive. Finally, Maryland passed the Maryland Online Data Privacy Act of 2024 — a law that many have argued is the most consumer-friendly law enacted to date.

Maryland's law departs from the WPA framework in numerous ways, including its approach to data minimization, sensitive data, minor's data privacy and unlawful discrimination. Its data minimization provisions in particular usher in a new paradigm, or what one article referred to as a "significant milestone in the rise of data minimization."

Maryland's law creates different data minimization rules based on whether the data at issue is personal or sensitive. For personal data, controllers must limit their collection "to what is reasonably necessary and proportionate to provide or maintain a product or service requested by the consumer to whom the data pertains."

For sensitive data, controllers may not collect, process or share sensitive data unless it is "strictly necessary to provide or maintain a specific product or service requested by the consumer to whom the personal data pertains." That provision diverts from other WPA variants, which require controllers to obtain consumer consent to process sensitive data or, in the case of Iowa and Utah, provide notice and offer an opt out. Maryland's law also prohibits the selling of sensitive data.

Following in Maryland's footsteps, lawmakers in Maine and Vermont also attempted to pass data privacy legislation with more restrictive data minimization provisions. Both bills were the products of multiyear work groups and eventually failed, with the Maine bill failing in the Senate and the Vermont bill being vetoed by the state's governor.

Ultimately, however, the message from these lawmakers is clear. They believe existing laws have not done enough to rein in what they view as unacceptable data collection and use practices. On the other hand, these novel data minimization provisions have proven controversial with some arguing they are impractical. For example, MODPA's provisions raise numerous questions, such as how controllers should define a product or service and what role, if any, consumer consent plays in driving compliance.

Although it ultimately did not become law, Vermont's data privacy bill also prompted considerable controversy, resulting in the bill becoming the first state consumer data privacy bill to be vetoed. The primary point of contention was the bill's inclusion of a limited private right of action focused on the processing of sensitive data by large data holders. After the bill passed the legislature, business advocates launched an aggressive veto campaign, including running advertisements on various social media platforms. The bill sponsors pushed back with an op-ed but, in the end, they could not secure the necessary votes in the Senate to override the veto.

The bill's primary sponsor, Rep. Monique Priestley, D-Vt., has already vowed to return in 2025 with another version of the bill.

Taking a step back, these three bills are not only a sign of a growing paradigm shift, they also reflect a shift in the framing of the state privacy law debate. For example, during committee hearings on the Maryland bill, one privacy advocate derided the Connecticut Data Privacy Act as an industry-sponsored bill. In an op-ed, legal scholars Neil Richards and Woodrow Hartzog argued the Connecticut Data Privacy Act is a "mockery of the rule of law" and that lawmakers who pass Connecticut-like laws "ought to be ashamed."

This stands in stark contrast to how the Connecticut law was viewed when it was passed just two years ago. In an August 2022 article, David Stauss characterized the Connecticut and Colorado laws as "unquestionably the most consumer-friendly of the four" WPA-model laws passed to date.

At the time it cleared the legislature, the IAPP reported its passage was "no small feat," and Consumer Reports applauded "Connecticut lawmakers for advancing meaningful privacy legislation that will help protect the personal information of their constituents."

The recasting of the Connecticut law from a leading consumer protection law to a "mockery of the rule of law" in just two short years demonstrates how rapidly the state privacy law debate has changed. It also shows how concepts that were once accepted as settled are susceptible to rapid change as new voices enter the debate

In the end, the carefully constructed interoperability between state laws that has hitherto allowed a state-led approach to U.S. privacy protections to function could be giving way to a patchwork of incompatible and diverging requirements.

New laws iterating on existing models: Minnesota, New Jersey and Rhode Island

While some 2024 laws and bills sought to break new ground for state data privacy rights and protections, the bills passed in Minnesota, New Jersey and Rhode Island more or less sought to build upon the existing model.

The most notable of these new laws is perhaps Rep. Steve Elkins Minnesota Consumer Data Privacy Act. After years of dedicated work on comprehensive data privacy legislation, Elkins, D-Minn., finally found success with passage of his bill this year. Minnesota's new law is based on the WPA model but contains several unique requirements and provisions, including a novel right to question the result of an adverse profiling decision, a new definition of precise geolocation data and new privacy program requirements including an obligation for controllers to maintain a data inventory.

New Jersey's law is also built on the WPA model but contains a few notable variations such as a broader definition of sensitive data that includes financial information. It also is the third state — after California and Colorado — to mandate rulemaking.

Finally, the Rhode Island law diverges from the WPA format by including a unique privacy notice provision that requires entities to disclose the third parties to whom they sell or "may sell" personally identifiable information and by omitting some provisions that have become commonplace in recently passed laws, such as data minimization language and an obligation to recognize universal opt-out mechanisms.

The rest: Kentucky, Nebraska and New Hampshire

Not every law that passed in 2024 contained unique provisions. Rather, Kentucky, Nebraska and New Hampshire passed bills that are near copycats of existing laws.

In Kentucky, after years of Sen. Whitney Westerfield, R-Ky., proposing bills that would have gone further than existing state laws — one of Westerfield's bills even passed the Kentucky Senate in 2023 — the legislature adopted a competing Virginia copycat bill primarily based on the argument that Kentucky did not want to adopt a law that was not in line with existing laws passed in other states.

Nebraska lawmakers chose to model their law after last year's Texas data privacy law. Finally, New Hampshire lawmakers looked to an earlier version of the Connecticut law — before it was amended in 2023 — as their model.

Updates to existing privacy laws

Privacy pros must be aware not only of new states joining the comprehensive privacy law club, but also how the requirements under existing laws are changing over time. This year, four existing data privacy laws received amendments: Colorado, California, Virginia and New Hampshire, with lawmakers most commonly focusing on expanding protections for children's and teens' data.

These amendments reflect an accelerating trend of lawmakers returning to update and iterate upon their privacy statutes year after year, frequently informed by new privacy requirements in other jurisdictions.

California led the way with updates this year, passing six total amendments to the California Consumer Privacy Act, many of which are still awaiting final approval from Gov. Gavin Newsom, D-Calif., at time of writing.

The most significant amendment is AB 1949 which requires affirmative authorization, an undefined term, for the collection, use and sharing of the personal information of minors under 18 years old. It also provides that individuals may communicate their age to companies through not-yet-developed device signals. AB 3048 will require browsers and mobile operating systems to offer settings that allow consumers to exercise their rights to opt out of the sharing of personal information and to limit the use and disclosure of their sensitive information on a default basis. AB 1884 will require businesses that acquire other companies to honor prior opt-out requests.

California lawmakers also tinkered with the scope of covered data through a pair of CCPA amendments: SB 1223 and AB 1008. Together, these bills will explicitly include neural data as a category of sensitive information under the CCPA and provide that personal information can exist in a variety of formats, including artificial intelligence systems capable of outputting personal information. The latter change sets up a potential divergence between American and European privacy law, as Hamburg's data protection authority, the Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information, recently released a discussion paper arguing large language models do not store personal data. Finally, California has enacted AB 3286, which ties the CCPA's applicability thresholds to the consumer price index.

The Colorado legislature was also active on privacy this year, adopting three amendments to the Colorado Privacy Act.

First, lawmakers enacted a children's privacy amendment modeled very closely on changes to Connecticut's privacy law that passed last year. The centerpiece of this emerging legislative approach is a duty of care for companies to avoid heightened risk of harm to minors caused by using an online service, product or feature.

Next, the legislature passed an amendment that creates new rights and obligations with respect to the processing of biometric data and biometric identifiers. Significantly, this bill covers the biometric information of employees, making Colorado the second state after California to extend privacy rights to individuals acting in an employment context through a comprehensive consumer privacy statute.

Finally, Colorado adopted an amendment to explicitly include neural data used for identification purposes as a category of sensitive data under the Colorado Privacy Act. However, in the rush to crown a "first neural privacy" law in the United States, this #bill has been widely misunderstood and its practical impact will likely be largely symbolic.

Lawmakers in Virginia introduced almost a dozen proposed amendments to the Commonwealth's data privacy law this year, but ultimately only one was enacted. The successful bill is a narrow amendment focused on children's data, which expands data minimization provisions and risk assessment requirements for the personal data of children under 13 years of age.

However, this amendment was only adopted following a tense back and forth between Gov. Glenn Youngkin, R-Va., and the Democrat-controlled legislature. The governor sought to raise the age threshold for child data under the landmark Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act from 13 to 18 years of age. While this arguably would have expanded privacy protections, it also could have triggered constitutional vulnerabilities.

Finally, New Hampshire's comprehensive privacy law, enacted in March, received a minor amendment in August to remove a mandate that the secretary of state conduct rulemaking regarding privacy policies and the exercise of consumer rights, instead making these self-executing provisions.

Rulemaking activity

It was a relatively quiet year on the rulemaking front as the majority of state comprehensive privacy laws continue to decline to direct state regulators to promulgate implementing rules for new privacy laws.

This year's primary exception was Florida, where the Department of State completed an under-the-radar, but potentially significant, rulemaking process under the Florida Digital Bill of Rights, a substantively broad privacy statute that only applies to a handful of very large companies in particular lines of business. The final rules include several controversial provisions, including tying the common "actual knowledge or willfully disregards" standard to age verification in certain circumstances, and requiring regulated industries to comply with the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology's risk management framework SP 800-37 to satisfy cybersecurity requirements.

On the horizon, California represents an impending storm for privacy rulemaking. Following years of prerulemaking activity, the California Privacy Protection Agency Board intends to soon enter formal rulemaking on regulations governing opt-out rights for automated decision-making technologies, risk assessments, cybersecurity audits, insurance and updates to existing regulations.

The rulemaking process is likely to be hotly contested as the proposed regulations include various novel and far-reaching provisions for a U.S. legal context, and the agency estimates they will cost California businesses more than USD4 billion in the first year of adoption. Notable provisions include a requirement that businesses affirmatively send reports about completed risk assessments to the agency. Members of the business community have also repeatedly expressed concerns that the proposed cybersecurity audit rules would function as a "backdoor" for new substantive security standards.

Numerous influential Californians, including CPPA Board Member Alastair Mactaggart, have also raised concerns about the breadth of the proposed opt-out rights for automated decision-making technology. Other observers have argued these provisions risk stymying California's leadership in AI and would inappropriately leapfrog the state legislature in establishing new guardrails for these technologies.

Finally, while the agency has yet to move forward with these regulations, it initiated formal rulemaking on rules for data broker registration.

Looking further ahead, New Jersey is expected to initiate a rulemaking pursuant to its new privacy law, scheduled to take effect in January 2025, and Colorado may also consider adopting new rules to implement its new children's and biometric privacy amendments. But in many states, attorney general guidance, advisory opinions and, ultimately, enforcement activities will likely be the main avenues to provide legal clarity on obligations under new privacy laws.

Enforcement continues to ramp up … slowly

Though there are 19 comprehensive state privacy laws on the books, the U.S. is in many ways still in the opening stage of the emergence of an individual state-led regime for protecting consumer privacy. New state privacy laws took effect in Oregon and Texas this year, with Montana on the way, which will bring the total number of states with privacy laws in effect to eight.

However, most of these states remain in "right to cure" periods, meaning most of the ongoing enforcement activity will likely take place out of the public eye. In fact, 2024 saw only two new final public enforcement actions of a state comprehensive privacy law, both carried out by the California attorney general. The first action involved DoorDash's alleged participation in a data sharing cooperative for the purposes of targeted advertising. The second action against Tilting Point Media, creator of the popular game Spongebob's Krusty Cook Off, involved the collection and sale of children's data.

Despite the dearth of flashy settlement announcements, there are plenty of indicators state privacy enforcement is ramping up.

In February, the Connecticut attorney general issued a report detailing its enforcement activity, which included more than a dozen violation notices and the office's areas of focus, including privacy policies, sensitive data and information of teens. California's privacy regulators also announced a number of enforcement sweeps, including in perhaps unexpected sectors such as streaming apps and devices and connected vehicles. States with upcoming privacy laws have also taken steps in preparation for enforcement, such as Delaware's Personal Data Privacy Portal and New Hampshire's creation of a new Data Privacy Unit.

There also are indications that states place a renewed emphasis on carrying out privacy enforcement activities under more general authority to police unfair and deceptive acts and practices, such as under Unfair, Deceptive, and Abusive Practices laws or mini-U.S. Federal Trade Commission acts.

Texas, which is shaping up to be a major player for enforcement with the launch of a new privacy and security initiative, recently brought a lawsuit against a car manufacturer alleging deceptive practices with respect to the sale of driver data for insurance scoring. New York invoked its state UDAP law to issue guidance on online tracking technologies, even though the state lacks a consumer data privacy law.

This emerging trend adds another layer of complexity to compliance for privacy pros who are already struggling to keep up with new laws.

Ultimately, while privacy pros are drawn to characterizing laws as either strong or weak, recent activity suggests in reality regulatory capacity and interest to pursue enforcement activity is at least as important in evaluating the impact of a privacy law as its substantive requirements.

Conclusion

This year's state legislative session was the most varied and, in many ways, the most contested to date for comprehensive state privacy law activity. While privacy pros and lawmakers continue to recognize that many of these issues would ideally be addressed on a national level, the prospects of a comprehensive federal privacy law seem further away than ever, as work on the American Privacy Rights Act proposal lost momentum even quicker than its 2022 predecessor, the American Data Privacy and Protection Act.

In the absence of a federal privacy approach, state legislative activity continues to accelerate as the potential harms of mass data collection and processing become more concerning to lawmakers. This has been true not only with broad-based comprehensive privacy legislation, but also with narrower sectoral privacy laws.

Keir Lamont, CIPP/US, is senior director of the U.S. Legislation team at the Future of Privacy Forum. David Stauss, CIPP/E, CIPP/US, CIPT, FIP, PLS, is a partner at Husch Blackwell.

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Submit for CPEs