Intangible Privacy Harms Post-Spokeo

Contributors:

Calli Schroeder

Global Privacy Counsel

The Electronic Privacy Information Center

Editor's Note:

Earlier this week, counsel for the parties inSpokeo v. Robinsparticipated inoral argumentson the remanded case before for the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. At issue is whether Spokeo’s alleged procedural violations of the Fair Credit Reporting Act harmed Robins in a way that courts can redress.

The three-judge panel pressed counsel to distinguish between the legal right – the claim or cause of action – and the injury. Sometimes, counsel argued, they are one and the same such as in the case of a violation of a constitutional right like free speech, but sometimes the legal violation is insufficient and must be coupled with a demonstrated injury, even an intangible one.

As counsel for Robins argued “the intangible harm the FCRA protects has a close relationship to a harm traditionally provided as a basis for suit in American and English; and even if it does not, Congress appropriately protected by statute a modern intangible interest for which consequential harm is especially difficult to prove or measure.” Counsel admitted that the parties throughout the litigation have used the terms “interest, injury and harm” interchangeably.

Confused?

This article by Westin Research Fellow Calli Schroeder aims to shed light on the matter by examining how intangible harm cases have fared under the Supreme Court’s Spokeo standards.

The United States Supreme Court’s ruling in Spokeo v. Robins last May aimed to clarify standing requirements for privacy-related class-action lawsuits under Article III of the U.S. Constitution. Specifically, Spokeo brought to the foreground two key points: that particularization and concreteness are distinct but necessary standing requirements, and that a concrete harm may be either tangible or intangible to meet Article III standing.

Particularization and concreteness have featured in class-action rulings for decades, of course, but the notion of an intangible concrete harm raises new questions about how lawyers can successfully demonstrate such harm in court.

This article examines privacy-based cases that have addressed the intangible harm threshold in the months following the Spokeo ruling.

Establishing Article III standing

Under Article III of the U.S. Constitution, a court may issue an opinion when there is a clear “case or controversy” present in the matter. A plaintiff may not merely allege a statutory violation but must also demonstrate an “injury in fact.” This requires that the plaintiff’s injury be traceable to the defendant’s action and that the injury be something for which the court can provide redress. More specifically, the plaintiff’s injury must be both concrete and particularized and actual or imminent. The Spokeo decision emphasizes that concreteness and particularization are distinct requirements from one another and that the plaintiff must clearly assert both factors in order to maintain standing.

Particularization requires that the injury affects the plaintiff in a personal and individual way. Therefore, an injury to a general body of people is insufficient. The injury must have actually impacted the individual or individuals named as parties in the suit.

Where particularization requires that the injury affect the plaintiff, concreteness requires that the injury actually exist (be a “de facto” injury). A concrete injury may be established with either a tangible or intangible harm. Harm is the portion of the claim that is redressable by the court. Tangible harms range from physical injuries to monetary losses, while intangible harms may include invasion of privacy or denial of information. Although tangible harms tend to be easier to identify, the Spokeo decision provided guidance for determining when an intangible harm is also concrete.

What makes intangible harms concrete

In order to determine whether an intangible harm is concrete and therefore rises to the level of an injury in fact, the Supreme Court’s Spokeo ruling identified two factors to consider: 1) Is the alleged intangible harm closely related to a harm that has traditionally provided valid basis for a lawsuit, and 2) has Congress identified this intangible harm as one that meets Article III requirements.

The first factor broadly asks whether there is historical precedent for regarding the specific intangible harm as a cognizable and redressable injury. For example, a client being pestered by robocalls may successfully establish that the unwanted calls constitute an intangible harm by showing that the calls are analogous to an intrusion upon seclusion, a specific privacy tort listed in Restatement Second of Torts, 652(b). As more privacy cases allege intangible harms as the basis for standing, we will gain a clearer picture of commonly accepted intangible harms that are linked with historically established claims.

The second factor to consider when determining if an intangible harm is concrete is whether Congress has identified that harm as sufficient to establish an injury through Congressional action. The Spokeo ruling stated that “Congress is well positioned to identify intangible harms that meet minimum Article III requirements.” Congress “has the power to define injuries and articulate chains of causation that will give rise to a case or controversy where none existed before.” This will often be through passing statutes that identify a specific harm, such as prohibiting robocalling under the Telephone Consumer Protection Act or punishing the failure to provide certain debt-related information to consumers under the Federal Credit Reporting Act.

A statute’s wording offers guidance on how Congress views the severity of the harm in question and can assist courts in determining whether the harm stemming from the statutory violation is sufficient to establish concreteness. This is not to say that all statutory violations will automatically satisfy the injury in fact requirement without some further established harm – as Spokeo makes clear - but merely that there may be circumstances where the statutory violation alone is a sufficient harm.

Determining concrete intangible harms in practice

Spokeo was decided recently, so the concrete intangible harms boundaries have not yet been fully explored. However, Spokeo and two rulings since Spokeo describe and clarify the boundaries of what constitutes an intangible harm. Comparing the ruling in Mey v. Got Warranty, Inc. (Northern District of West Virginia) and the ruling in Jackson v. Abendroth & Russell, P.C. (Southern District of Iowa) helps to form a picture of how courts perceive the connection between intangible harms and concreteness.

In Spokeo, the court noted that a mere procedural violation of a statute may sometimes be sufficient to constitute injury in fact. For example, voters’ intangible harm constituted a cognizable injury in fact when they were denied information from the Federal Election Commission to which they were entitled under the Federal Election Campaign Act. The statutory violation itself – denial of the information – served as an intangible harm sufficient to establish concreteness and standing for the plaintiffs. When considering whether a statutory violation is itself sufficient to establish a concrete intangible harm, courts must look at whether the harm is closely related to a traditionally valid harm or whether Congress identified the harm as sufficient.

The court in Mey v. Got Warranty, Inc. applied Spokeo’s standards for intangible harms to telemarketing calls directed at a number registered on the National Do Not Call Registry. Such calls are in violation of the TCPA. The Mey court determined that these calls caused three types of intangible harms: 1) invasion of privacy, 2) intrusion upon and occupation of cell phone capacity, and 3) waste of time and risk of personal injury based on interruption and distraction. The court then discussed why each type of intangible harm is concrete.

The first type, invasion of privacy, is closely related to a traditionally valid harm. Not only is it recognized as a common law tort by itself in many states, it is also analogous to “intrusion upon seclusion,” a tort listed in the Restatement (Second) of Torts. Both the common law and a specific tort closely linked with the harm provide sufficient basis to consider invasion of privacy a concrete intangible harm. Additionally, Congress clearly identified invasion of privacy as a legally cognizable harm by stressing consumers’ right to privacy repeatedly throughout the TCPA. The repeated emphasis marked it as a primary concern of the TCPA and served to establish that this harm by itself is concrete.

The second type of harm, intrusion upon and occupation of cell phone capacity, closely relates to the ancient common law tort of trespass to chattels. The Mey ruling provides a litany of cases supporting this connection and, in fact, applying the tort theory to unwanted telephone calls specifically. Based on this understanding, “the TCPA can be viewed as merely applying this common law tort to a 21st-century form of personal property and a 21st-century method of intrusion.” This clear connection between the statutory violation and the historically recognized tort make this type of violation a concrete harm.

Finally, wasted time, interruption and distraction constitute the last type of harm. Other post-Spokeo decisions have recognized wasting the recipient’s time as a concrete injury that satisfies Article III. Congress repeatedly recognized the nuisance, interruptions and wasted time caused by robocalls as one of the harms that the TCPA sought to remedy.

The Mey court applied both Spokeo factors in its analysis of each type of harm recognized: 1) whether the alleged harm was linked to a traditionally recognized harm and 2) whether Congress had identified the harm as sufficient. This analysis demonstrates that courts are taking the Spokeo ruling seriously and adopting factors in its ruling when evaluating intangible harms for Article III standing.

Conversely, the court in Jackson v. Abendroth & Russell, P.C. found that a statutory violation alone was insufficient to constitute a concrete intangible harm. The plaintiff alleged that debt collection letters sent by the defendant violated the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act by failing to include separate informational disclosures required by the act. Further, he claimed that the violation itself was an intangible harm sufficient to establish Article III standing.

Applying the Spokeo court’s concrete harms analysis, the Jackson court ruled that the statutory violation was not a concrete intangible harm. The court determined that both statutory failures Jackson claimed related to his ability to dispute his debt. Because there was no indication that Jackson ever intended to dispute his debt, however, he did not suffer a redressable harm or the material risk of a harm that Congress had identified as an intangible harm through the statute.

Additionally, this violation mirrors the Supreme Court’s example in Spokeo of a statutory harm that does not rise to the level of intangible harm: “A violation of one of the FCRA's procedural requirements may result in no harm. For example, even if a consumer reporting agency fails to provide the required notice to a user of the agency's consumer information, that information regardless may be entirely accurate.” Jackson did not claim that the harm he alleged was closely connected to another recognized harm, nor could he establish that Congress had identified the harm he suffered as a valid intangible harm.

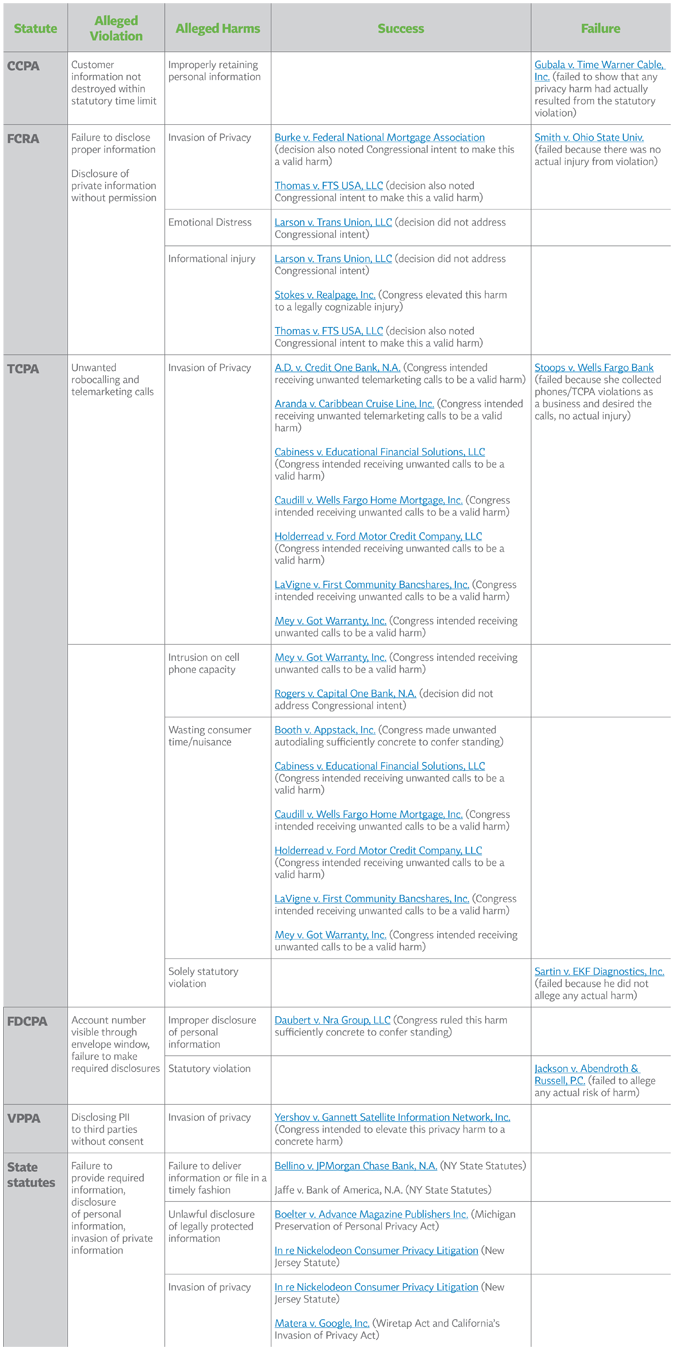

Table of Intangible Harms Established since Spokeo

The following table includes privacy law decisions since Spokeo that have referenced the ruling and specifically addressed the issue of intangible harms. It appears there have been more successes than failures to establish intangible harms. However, this may be skewed because many cases that failed to establish intangible harms were dismissed before the court brought up intangible harm criteria. Instead, those cases were often dismissed for failing to meet the concreteness requirement.

This provides a brief history of the statutes under which most cases alleging intangible harms have been brought and describes which specific harms or arguments have been successful. In establishing a concrete intangible harm, Plaintiffs must link the harm to a traditionally recognized harm, establish that Congress identified this intangible harm as meeting Article III requirements, or establish both. “Alleged harms” identify the recognized harm Plaintiffs attempted to link to the intangible harm in the case. Parentheticals after each case state whether the harm was one identified by Congress. If there was no harm at all in the case, there could be no harm that Congress identified as satisfactory.

Editor's note:

Earlier this week, counsel for the parties inSpokeo v. Robinsparticipated inoral argumentson the remanded case before for the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. At issue is whether Spokeo’s alleged procedural violations of the Fair Credit Reporting Act harmed Robins in a way that courts can redress.

The three-judge panel pressed counsel to distinguish between the legal right – the claim or cause of action – and the injury. Sometimes, counsel argued, they are one and the same such as in the case of a violation of a constitutional right like free speech, but sometimes the legal violation is insufficient and must be coupled with a demonstrated injury, even an intangible one.

As counsel for Robins argued “the intangible harm the FCRA protects has a close relationship to a harm traditionally provided as a basis for suit in American and English; and even if it does not, Congress appropriately protected by statute a modern intangible interest for which consequential harm is especially difficult to prove or measure.” Counsel admitted that the parties throughout the litigation have used the terms “interest, injury and harm” interchangeably.

Confused?

This article by Westin Research Fellow Calli Schroeder aims to shed light on the matter by examining how intangible harm cases have fared under the Supreme Court’s Spokeo standards.

Contributors:

Calli Schroeder

Global Privacy Counsel

The Electronic Privacy Information Center