Bipartisan consensus in US privacy lawmaking

Contributors:

Müge Fazlioglu

CIPP/E, CIPP/US

Principal Researcher, Privacy Law and Policy

IAPP

In 2023, U.S. Congressional activity marched toward — but ultimately never made it to — the summit of passing a comprehensive federal consumer privacy law. Indeed, the nature of progress has been affected by at least two related developments that appeared suddenly this year.

First, the number of state privacy laws on the books increased to 12, with Delaware, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, Oregon, Tennessee and Texas joining the list. Not only has 2023 seen more state privacy laws enacted than any prior year, but five states' laws — those in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Virginia and Utah — became or will become effective sometime in 2023. Collectively, residents of these states make up about 34% of the U.S. population, meaning about one in three U.S. residents is already or will soon be protected by a comprehensive state privacy law. Arguably, state legislatures stepping up to fill the privacy void reduces some of the pressure on Congress to act.

Second, the increasing uptake of artificial intelligence technologies has gripped the attention of law and policymakers around the world. AI has brought about social and economic upheaval, along what Harvard Business School postdoctoral Research Fellow Fabrizio Dell'Acqua and his coauthors named the "jagged frontier." Given this, the White House, Congress and federal agencies including the Federal Trade Commission, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and National Institute of Standards and Technology have unleashed a flurry of initiatives, programs and legal guidance to provide greater clarity for companies within the rapidly growing AI economy.

Yet, although both these developments add complexity to regulating personal data, Congress has not abandoned its efforts on passing comprehensive federal privacy legislation.

Indeed, nearing the halfway point of the 118th session of Congress, at least 50 bills related to privacy have been introduced. This means the current Congress resembles most others in recent years with regard to their privacy-lawmaking activities. For example, approximately 100 privacy-related bills were introduced throughout the entirety of the 117th Congress. As in previous years, the bills introduced vary in scope, covering the domains of consumer, financial, health information, children's and educational privacy, and impose privacy and data security-related obligations on various government agencies.

Consumer privacy bills with bipartisan support in the 118th Congress

To date, four bills that enhance privacy protections for U.S. consumers, employees or individuals introduced within the 118th Congress have received support from both Democrats and Republicans.

Perhaps the most limited in scope of all the introduced bipartisan consumer privacy bills, the Informing Consumers About Smart Devices Act requires manufacturers of smart devices equipped with a camera or microphone to disclose this fact to consumers prior to purchase. The requirements of this bill would not, however, apply to devices a consumer would reasonably expect to include a camera or microphone, such as mobile phones or laptops. Introduced in a previous session of Congress as well, the Senate version (S.90) was sponsored by Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, ranking member of the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation and received bipartisan support from chair of that committee Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., as well as committee member Sen. Raphael Warnock, D-Ga.

Another bipartisan piece of consumer privacy legislation is the Platform Accountability and Transparency Act, which empowers the National Science Foundation, in consultation with the FTC, to establish pathways for independent researchers to access data held by large internet companies. Akin to similar provisions in the EU Digital Services Act, the PATA Act provides the FTC with rulemaking authority to require social media platforms to make their data, metrics and other information available to qualified researchers. Notably, the bill was endorsed by the editorial board of the Washington Post, as well as the American Psychological Association, Mozilla and Common Sense Media, among others.

The Data Elimination and Limiting Extensive Tracking and Exchange Act, also known as the DELETE Act, establishes a centralized system allowing individuals to request deletion of their personal information from data brokers. It requires data brokers, defined as an entity that "knowingly collects or obtains the personal information of an individual with whom the entity does not have a direct relationship," to register annually with the FTC. Having been introduced in previous Congresses as well, the bill was introduced in June this year, around the same time the California Senate initially passed its own Delete Act.

Lastly, the Deceptive Experiences to Online Users Reduction Act, or DETOUR Act, prohibits large online operators from manipulating consumers into providing personal information or giving consent, while also prohibiting the design of online products that lead to compulsive usage by children. A reintroduction as well, the DETOUR Act takes aim at so-called "dark patterns" in a way that mirrors the California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act.

Partisanship with preemption and private right of action

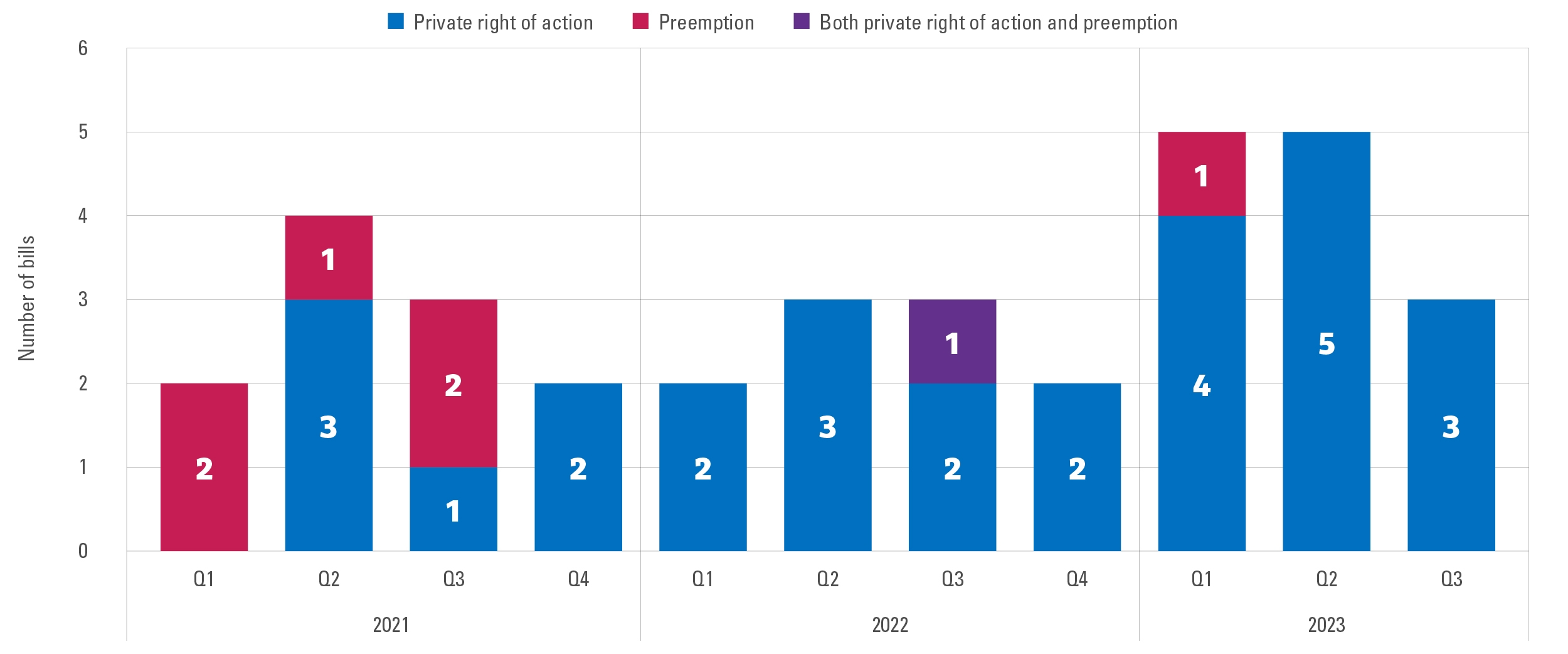

Taking a longer-term view of the U.S. federal privacy bills that have been introduced over the past few years, a couple of trends emerge regarding the two "partisan provisions" — preemption and private right of action.

Since 1 Jan. 2021, seven federal bills that would have preempted stronger privacy laws at the state level have been introduced. Importantly, five of these bills were sponsored/cosponsored only by Republicans. The American Data Privacy and Protection Act, which contained a preemption provision and had bipartisan support, and the Information Transparency and Personal Data Control Act are two exceptions. The latter, sponsored by Rep. Suzan DelBene, D-Wash., has been introduced multiple times, most recently in the 117th Congress in March 2021, and contained a preemption prevision but among its 29 cosponsors only included Democrats.

Over that same time frame, 28 federal bills containing a private right of action clause were introduced. In contrast to the bills with preemption, the bills that include a private right of action tend to be sponsored only by Democrats. This trend is also met with two notable exceptions. The Data and Algorithm Transparency Agreement Act, sponsored by Sen. Rick Scott, R-Fla., contained a private right of action clause, but was sponsored only by Republicans. As noted above, the ADPPA also contained a private right of action and had bipartisan support.

As indicated by the chart above, bills with private right of action clauses significantly outnumber bills containing preemption. In addition, as I have observed in previous studies of federal privacy bills, those supported by both Democrats and Republicans tend to contain neither of these "partisan provisions." Moreover, the bipartisan consumer privacy bills are usually narrower in scope, rather than comprehensive or omnibus, in terms of the consumer rights and business obligations they establish.

Again, the sole exception to this rule is the ADPPA, introduced in the House of Representatives in May 2022. Indeed, the ADPPA is the only federal privacy bill in recent years to contain both a private right of action and a preemption clause, making it truly an outlier. As of June, Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, R-Wash., was reportedly working to make the updated version of the bill more "business friendly" by weakening the private right of action clause.

Historical trends regarding two of the most contentious issues in the federal privacy debate — private right of action and preemption — indicate the collective preferences of Congress may have shifted over the past few years. Notably, preemption clauses, which tend to be included in bills sponsored solely by Republicans, have appeared with less frequency since 2021.

Conversely, private right of action clauses, which are only likely included when the sponsors of a bill are all Democrats, have become increasingly common over that same time period. Interestingly, when bills have bipartisan support, they tend to contain neither a private right of action nor a preemption clause. This dynamic holds true for all the bipartisan consumer privacy bills introduced so far within the 118th Congress, which contain neither private right of action nor preemption.

Federal privacy legislation as a precursor to AI regulation

In late August, Rep. DelBene, author of the Information Transparency and Personal Data Control Act, penned an op-ed in Newsweek arguing for the passage of a national data privacy law as a first step to making the U.S. "a global leader" of AI policy. Rep. McMorris Rogers, one of the cosponsors of the ADPPA, echoed the concern, saying it is "paramount" to pass comprehensive privacy legislation "before jumping into any AI legislation." Meanwhile, speaking to Roll Call in late September, Sen. John Hickenlooper, D-Colo., chairman of the Senate Commerce Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety and Data Security, expressed his support of full committee Chair Cantwell's commitment that, "at some point, perhaps not this year, but with a sense of urgency, we get a data privacy bill because that is going to underpin so much of what’s going to happen in terms of creating trust in AI."

Reaching a privacy compromise

Analyzing privacy-related legislation introduced in Congress over the past few years illustrates how the inclusion of private right of action and preemption clauses affects a bill's chance of attracting support from either side of the political aisle. Interestingly, what unites the consumer privacy bills with bipartisan support is a lack of both private right of action and preemption. For a true federal compromise on privacy legislation to occur, both sides may need to be willing to let go of their respective partisan provisions.

Despite the complex backdrop of comprehensive state privacy laws and the focus on AI governance initiatives, the pace of privacy bills introduced by Congress shows no signs of relenting. Yet, partisan differences over key issues within the federal privacy debate remain. While these dynamics will likely continue to produce protracted discussions, a bipartisan consensus — around a narrower scope of federal privacy protections, if nothing else — can still be forged.

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Submit for CPEsContributors:

Müge Fazlioglu

CIPP/E, CIPP/US

Principal Researcher, Privacy Law and Policy

IAPP

Tags: