UK data protection reform: What is in the government’s proposals?

Contributors:

Emma Drake

Partner

Bird & Bird

Ruth Boardman

Partner, Co-head, International Data Protection Practice

Bird & Bird

In September 2021, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport consulted on the future of U.K. data protection law. DCMS published its response to this consultation, and a first draft of the new bill is expected imminently.

DCMS recommends several changes to U.K. law. None represents a total overhaul in approach — the U.K. will retain “U.K. General Data Protection Regulation,” its existing Data Protection Act and its existing ePrivacy regulations, along with most of their existing provisions. Some changes are relatively minor tweaks intended to resolve perceived uncertainties. Others are more substantial, especially those to accountability requirements and the U.K. Information Commissioner's Office powers and priorities.

These proposals can broadly be grouped as changes to:

- Accountability.

- Reuse of data and research.

- Data subject rights.

- Data transfers.

- ePrivacy.

- Legitimate interests and lawful basis.

- AI and automated decisions.

- The ICO.

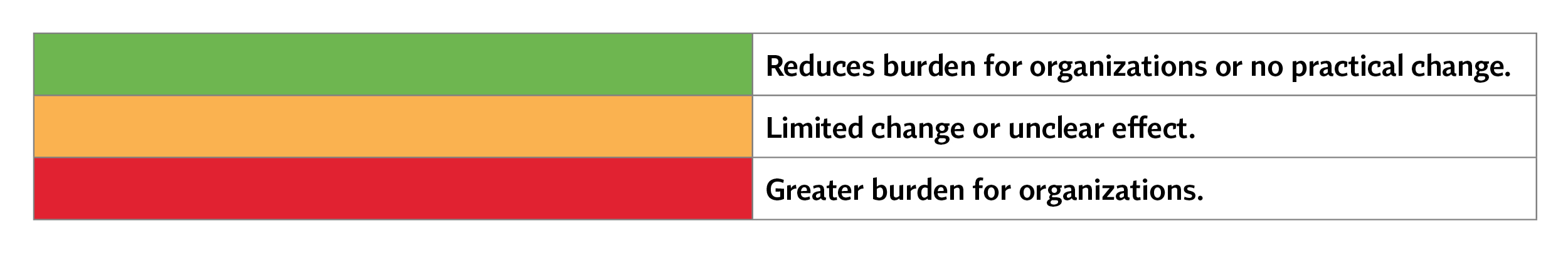

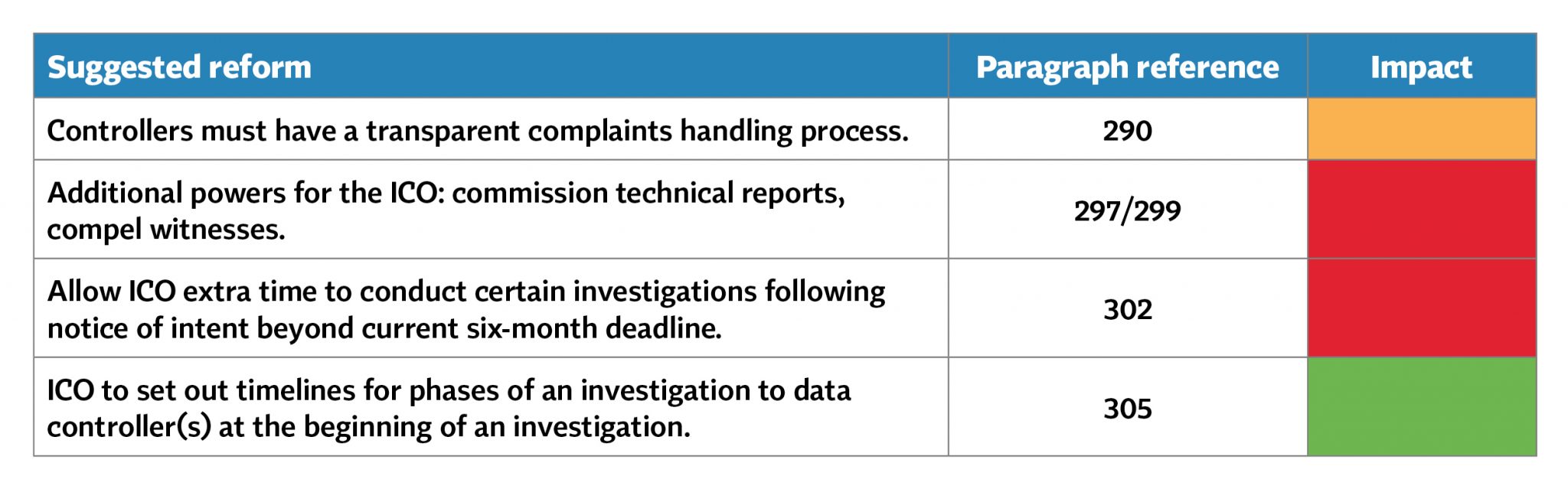

We have summarized these proposals below; color coding shows the degree of change these represent for an organization’s compliance:

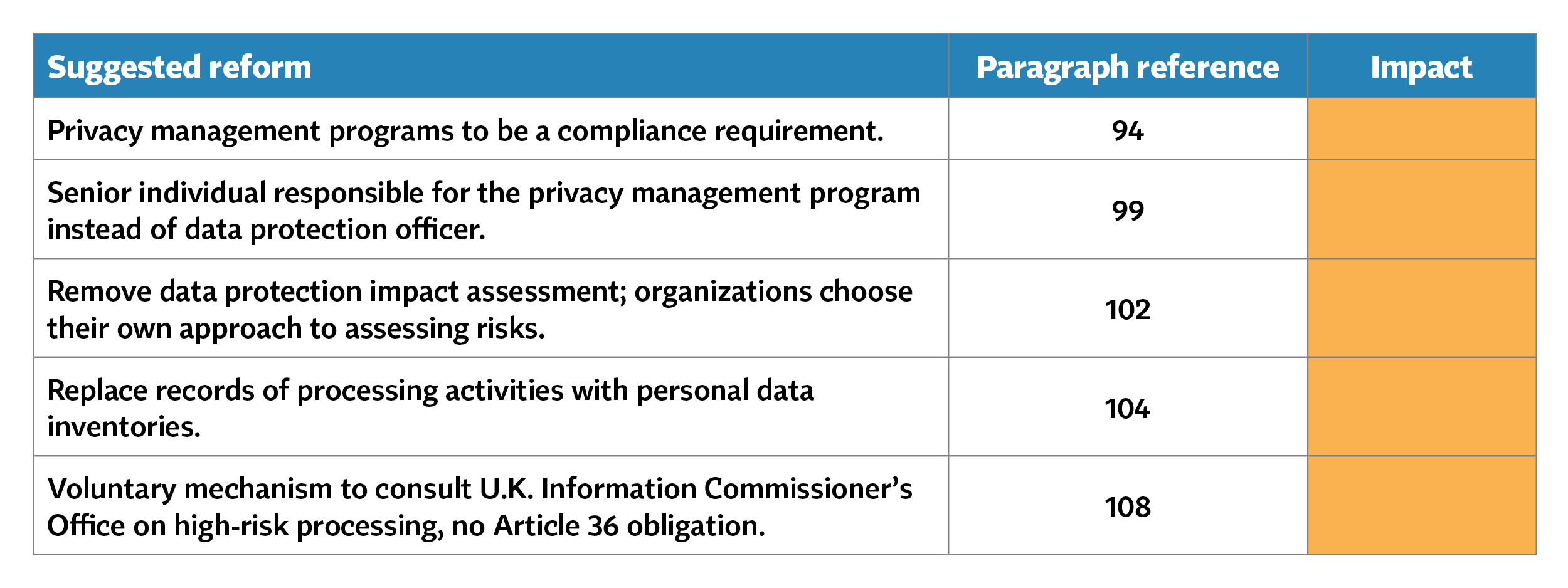

Accountability

DCMS suggests that removing specific accountability requirements will contribute to “£1 billion in costs savings” by reducing the business burden. Despite this lofty prediction, the proposals do not promise a wholesale reduction in administrative burden.

In summary, businesses must still hold inventories (but not quite the same as records of processing activities), must still assess the data protection impact of their activities (but not in the same way as a DPIA), and must appoint a responsible individual (but not quite the same person as a data protection officer).

For businesses with a U.K.-only base, these changes could prove helpful. Much will depend on how the “risk-based approach” translates to legislation and how the ICO chooses to apply it. Those caught by the EU GDPR will likely continue to look to EU requirements to try and meet their U.K. obligations. The government predicts “organisations that are currently compliant with the UK GDPR would not need to significantly change their approach to be compliant with the new requirement.” An area of apparent divergence relates to privacy personnel: The EU GDPR frequently requires a DPO, who must be independent and free from conflicts of interest; by contrast, DCMS will require a “senior responsible individual.” Based on the proposals, it seems unlikely that the same individual could realistically perform both privacy roles for organizations caught by both requirements.

The proposed higher threshold for breach reporting, which would have offered a clearer reduction in burden, is one of the few measures dropped from the original consultation.

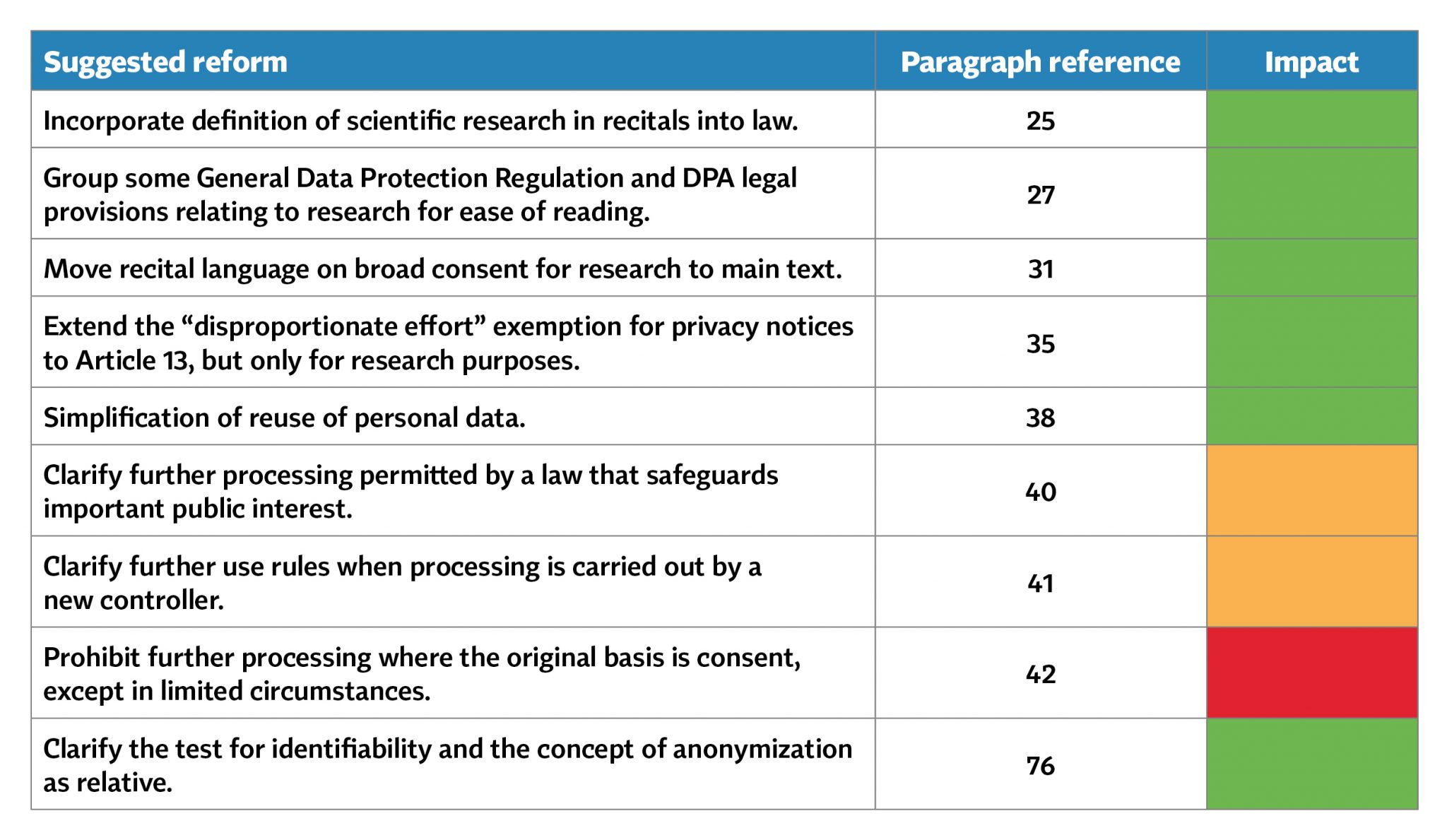

Reuse of data and research

DCMS proposes “clarifications” of the existing law: “scientific research” will be defined and provisions dealing with research reorganized to aid understanding. Rules around further use of data will also be clarified — it is not clear what this will involve. More than any other section of the proposals, the devil will be in the details of the drafting.

Where consent was the original legal basis, DCMS proposes that further processing for research should only be permitted in “very limited circumstances.” This may be restrictive for organizations reliant on consent, which cannot be refreshed — for example, where contact details are no longer held or where data is only held in pseudonymous form. This seems more likely to restrict research than offer encouragement.

More helpfully, DCMS proposes to extend the disproportionate effort exemption under Article 14 to data collected directly from data subjects. This will only be available for further processing carried out for research. A number of respondents had flagged concerns here, particularly in the area of longitudinal studies where pseudonymization and the combination of multiple data sets make it nigh impossible to re-contact data subjects.

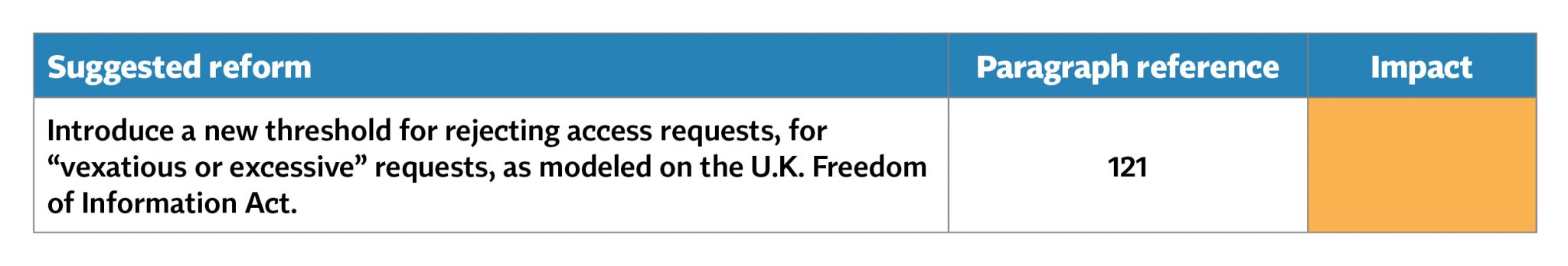

Data subject rights

The government has shied away from more radical proposals on subject access, particularly on imposing either U.K. Freedom of Information Act-style cost ceilings or nominal fees. Instead, DCMS will introduce a replacement threshold for rejecting or charging for a data subject access request, which will block “vexatious or excessive requests.” In the leading case of Information Commissioner v. Devon County Council & Dransfield in the Upper Tribunal, the judge emphasized the term "vexatious" needed to be interpreted “in the particular statutory context of FOIA, rather than in legislation generally.” Given the apparent importance of a statute’s specific context, it is not clear how importing the lengthy jurisprudence on vexatious requests for public access to public data will prove useful to controllers handling complex and expensive DSARs often brought by disgruntled employees. A lot will rest on ICO guidance and application — much like it does today.

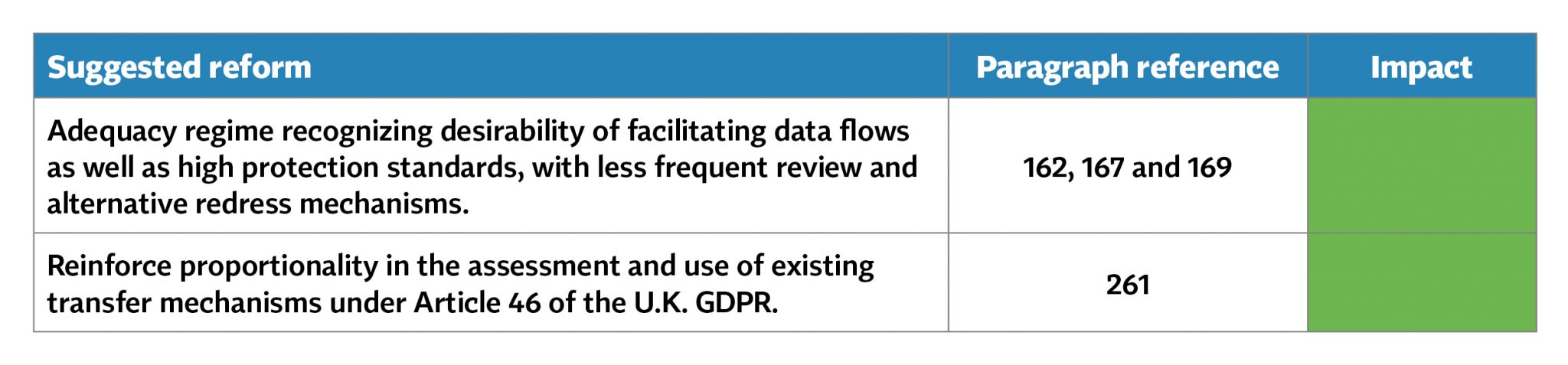

Data transfers

Proposals to widen existing exemptions under Article 49 to repetitive transfers and allow organizations to identify their transfer mechanisms outside of Article 46 have been dropped.

DCMS still proposes to amend requirements on assessment of other countries’ laws and safeguards under Article 46, to ensure these can be done more “pragmatically and proportionately” and to change the process for the U.K.’s adequacy assessment of third countries. There will be a continued insistence on high standards, but when met, the value in facilitating transfers with a particular country could be considered under DCMS’s proposals.

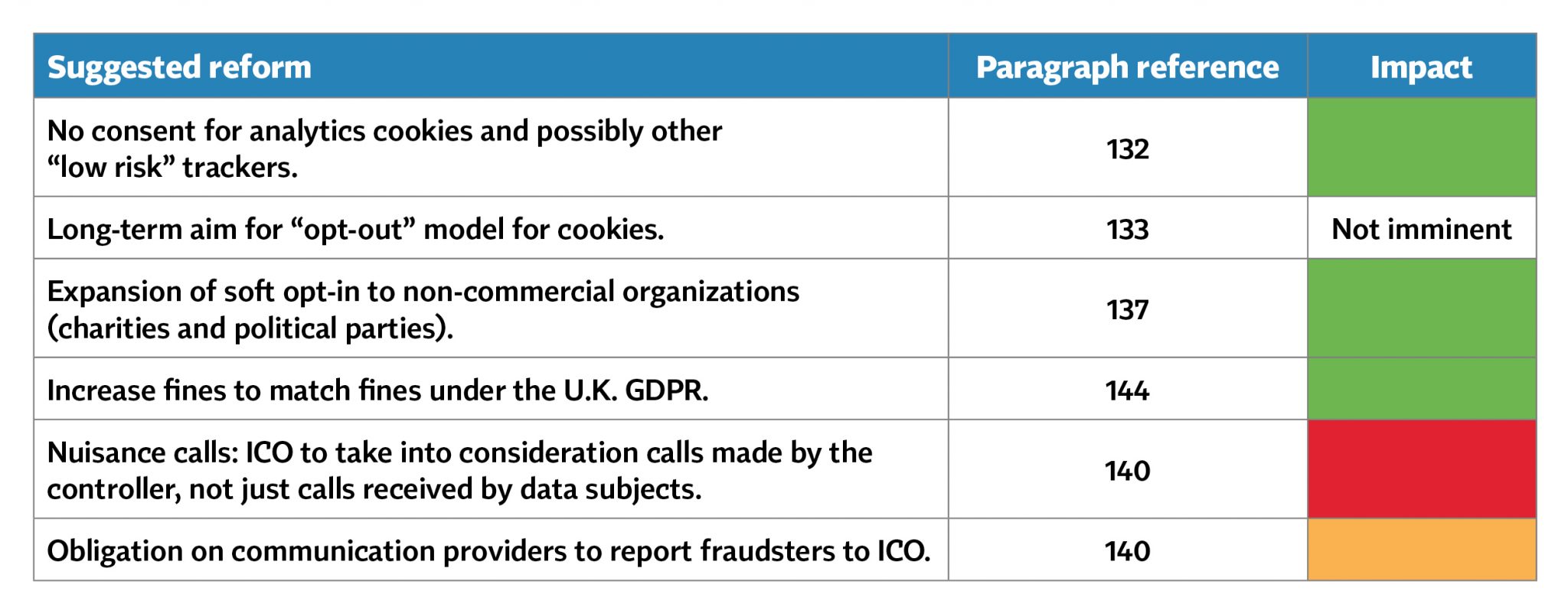

ePrivacy

Almost all of the changes proposed to the U.K.’s ePrivacy regime have survived consultation. These are mostly self-explanatory. A number of ministers and backbenchers longing for an imminent end to cookie banners, however, will need to wait and choose their websites carefully for this to become a practical reality.

A move to an “opt-out” model for cookies — trumpeted in DCMS’s press release — will only happen “when government assesses that (browser based and similar) solutions are widely available for use.” This may take longer than the expected lifespan of third-party cookies as behavioral advertising tools. In any event, this model will not be available for sites caught by the Age Appropriate Design Code. In the short term, consent will not be needed for certain “non-intrusive” purposes, such as analytics.

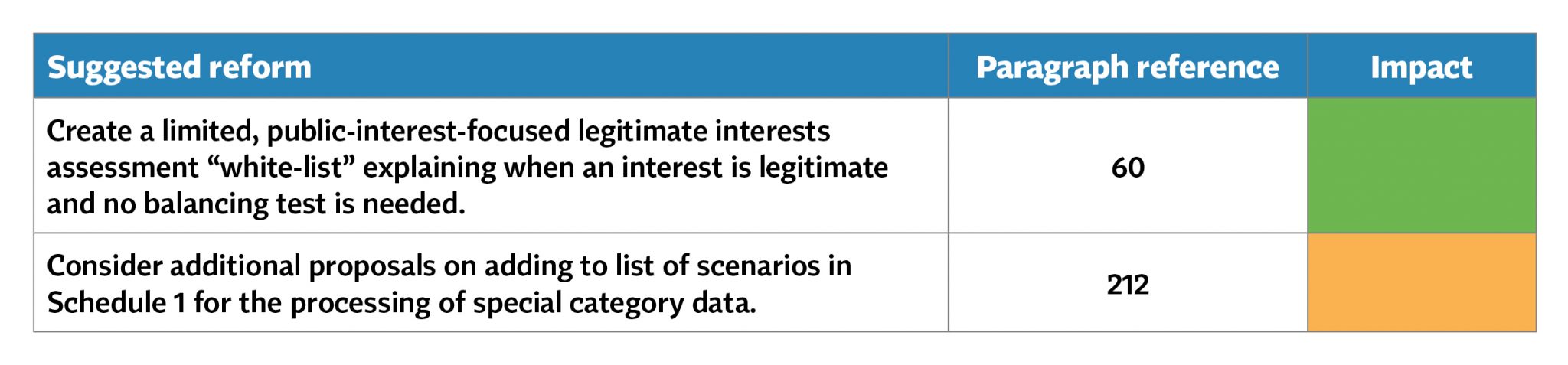

Legitimate interests and lawful basis

The government narrowed its proposal to create a list of legitimate interests for which no legitimate interest assessment would be needed. This offers the possibility to reduce the documentation burden of important processing, such as safeguarding children or preventing and detecting crime.

The government is also considering further proposals to extend or adapt existing grounds in Schedule 1; i.e., allow more processing of special category data where this is in the substantial public interest.

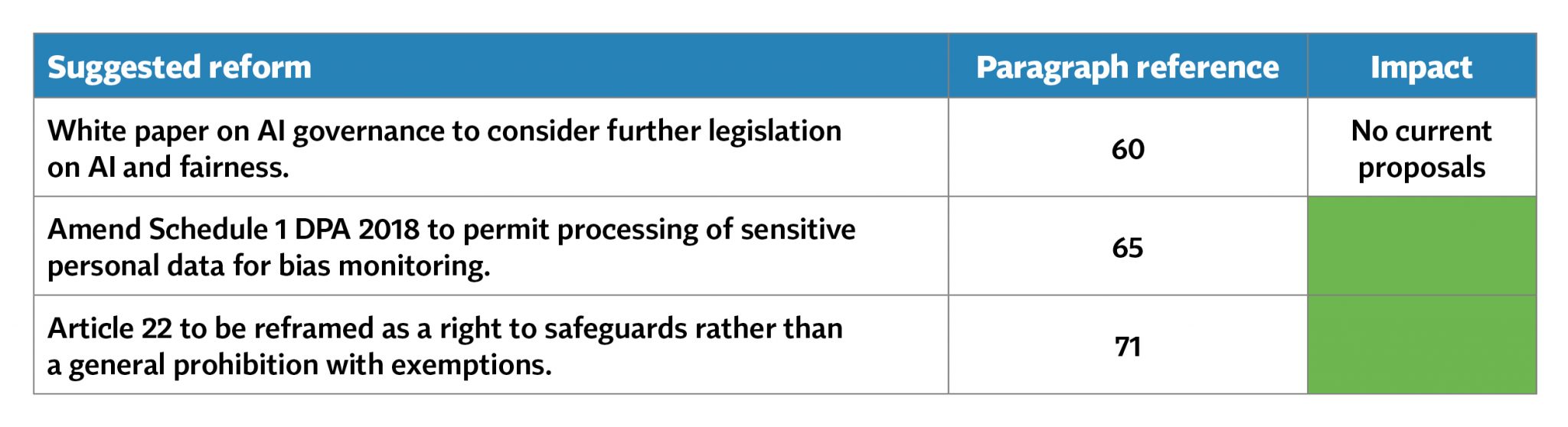

AI and automated decisions

The government’s consultation proposed reducing the burden of compliance on artificial intelligence innovation and ensuring fairness in machine learning. Many of these proposals have been dropped or moved to a proposed white paper on AI governance.

DCMS will still introduce a condition to explicitly permit the use of special category data for bias detection and correction. Article 22 will also be reframed to offer safeguards rather than its current prohibition of certain automated decisions. It is unclear from the proposal whether this amendment will be made now or wait for the envisioned white paper.

Reform of ICO

Some of the most substantial proposed changes are to the structure and priorities of the ICO. These will not necessarily lead to a big impact on the internal compliance obligations for businesses processing personal data — and so aren’t listed in our table above — but would impact the guidance and strategic focus of the ICO. In particular, the government proposes to:

- Move to a corporate model, where the current commissioner would be the chair of the ICO, with a separate CEO.

- Consider renaming the ICO.

- Put in place a statutory framework that sets out the ICO’s strategic objectives and priorities.

- Require the ICO to consider the desirability of promoting economic growth and the impact of its activities on competition and public safety.

- Require the ICO to engage and share data with some other regulators.

- Require the ICO to have a secondary regard to the DCMS Secretary of State’s “Statement of Strategic Priorities” when discharging its functions.

- Require the ICO to have DCMS approval for codes of practice and statutory guidance prior to laying them before Parliament. The rationale for approval/disapproval will need to be published by the Secretary of State.

- Reduce the need for the ICO to deal with low-level complaints and replace this with an obligation on controllers to have a transparent complaint handling process.

A majority of the consultation's respondents raised concerns with these proposals, particularly concerning the impact they might have on the ICO’s perceived independence from the government. These proposals may well be the main focus of EU adequacy concerns.

Next steps

The government is expected to move promptly to issue draft legislation in July. Once published, the passage of legislation through the Houses of Parliament leaves an opportunity for organizations to lobby for changes to the proposals and seek additional clarification and guidance on their impact.

Photo by James Giddins on Unsplash

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Submit for CPEsContributors:

Emma Drake

Partner

Bird & Bird

Ruth Boardman

Partner, Co-head, International Data Protection Practice

Bird & Bird