A recent Dutch court case has reinforced the obligation under existing EU data protection law for companies not established in the EU to appoint a representative in each member state in which they operate or else face potential penalties. Even as companies ramp up for the General Data Protection Regulation, which comes into force in May 2018, the 1995 EU Data Protection Directive remains in place and Data Protection Authorities expect compliance with the requirement for local representation.

The recent ruling by the Administrative Court in The Hague affirmed a DPA-imposed penalty against WhatsApp for its failure to appoint a representative in the Netherlands. This article explains the representative requirement under the Directive, and compares it to a similar requirement under the new GDPR, as well as to the additional obligation to appoint a data protection officer (DPO), in light of the WhatsApp decision.

The EU Directive’s Representative Requirement

The Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC generally requires European Union member states to impose data protection obligations only on companies that process personal data via an establishment within member state borders. However, Article (4)(1)(c) extends the Directive’s application to data controllers not established in the EU if they make use of equipment, automated or otherwise, situated on the territory of an EU member state for purposes of processing personal data.

Under Article (4)(2) of the Directive, any data controller not established in the EU is required to designate a representative in each EU member state in which it meets the 4(1)(c) requirements—that is, in every member state where it makes use of equipment for purposes of processing personal data. The requirement to appoint a local representative is meant to provide a point of contact for purposes of data protection enforcement against a foreign corporation, including to facilitate the collection of transnational administrative fines, an otherwise difficult task even across the borders of EU member states.

- Data controllers

The Directive requires controllers of personal data to designate a local representative. As the Directive defines it, a “controller” of personal data is the party that “determines the purposes and means of the processing” of that data. In contrast, a “processor” is any entity that processes personal data on behalf of the controller. The Directive does not require mere processors to designate a local representative.

- Makes use of equipment

A non-EU data controller that collects personal data of European citizens falls under Article 4(1)(c) if it makes use of equipment situated on the territory of an EU member state for purposes of processing personal data. According to the Article 29 Working Party, even minimal use, such as storing a single cookie on a European user’s device, will be sufficient to meet this standard. In its 2010 opinion, WP179, the Article 29 Working Party wrote that it “recognized the possibility that personal data collection through the computers of users, as for example in the case of cookies or Javascript banners, trigger the application of Article 4(1)(c) and thus of EU data protection law to service providers established in third countries.”

The Directive provides an exception when a company uses equipment “only for purposes of transit” through EU territory. As the Article 29 Working Party explained in the WP179 opinion, however, this exception will be rarely applied:

As this is an exception to the equipment criterion, it should be subject to a narrow interpretation. It should be noted that the effective application of this exception is becoming infrequent: in practice, more and more telecommunication services merge pure transit and added value services, including for instance spam filtering or other manipulation of data at the occasion of their transmission. The simple “point to point” cable transmission is disappearing gradually.

The WhatsApp Lesson

WhatsApp is a cross-platform mobile messaging app with more than a billion users worldwide that was acquired by Facebook in 2014. The Dutch DPA investigated WhatsApp in 2012, issuing a report in January 2013 that found WhatsApp had not yet appointed a representative in the Netherlands under Article 4(3) of the Dutch Personal Data Protection Act, the Dutch implementation of Directive Article 4(2). Specifically, the Dutch DPA was concerned with WhatsApp’s collection and processing of user address book data. When seeking other users to message through WhatsApp, a user of the app would grant it access to his or her list of phone contacts. This allowed WhatsApp to upload its users’ contacts—including names and phone numbers of non-users—to U.S. servers where it cross-referenced this data with a stored list of existing users. The DPA considered WhatsApp a “controller” under the Directive and the PDPA because it was processing the personal data of Dutch citizens in this way.

On July 22, 2014, due to WhatsApp’s continued failure to appoint a Dutch representative, the DPA issued a compliance order and imposed a 10,000-euro penalty for each day that WhatsApp failed to comply. WhatsApp sought review of the DPA penalty in the regional Administrative Court in The Hague, disputing the imposed penalty on multiple grounds.

On November 22, 2016, the Administrative Court ruled against WhatsApp. The court’s rejection of each of WhatsApp’s arguments carries important lessons for non-European companies operating in Europe.

- WhatsApp is a controller

WhatsApp contended that it was merely a processor for its users, and therefore not covered by the requirement to appoint a local representative under the Dutch PDPA. The court rejected this argument because WhatsApp had already admitted at oral argument that it was a controller of the personal data of its users.

- Users’ devices are equipment in the territory

WhatsApp argued that it was exempt from the PDPA because it did not have servers or other equipment located in the Netherlands. It therefore claimed that it was not making use of equipment in the Netherlands for purposes of processing personal data.

The court rejected this argument, referring to the 2013 Article 29 Working Party opinion WP202, which explained that an app installed on a mobile device will usually meet the “use of equipment” provision of the Directive because “the device is instrumental in the processing of personal data from and about the user” and “the app generates traffic with personal data to data controllers.” The Working Party identified one possible exception: “if the data are only processed locally, in the device itself.” According to the court, WhatsApp’s transmission of contact data from mobile phones in the Netherlands to its servers for comparison with existing user data thus constituted processing that made use of equipment located in the Netherlands. This analysis is consistent with decisions of other courts in Europe, including the 2014 High Court of Berlin ruling that Facebook was subject to German law due to its use of cookies on German computers.

The court also dismissed WhatsApp’s alternate argument that it was exempt from the law because it merely provided transit for its users, citing the Article 29 Working Party opinion WP179 quoted above.

- The representative stands in the controller’s shoes

WhatsApp next argued that the PDPA’s provision requiring appointment of a representative was inconsistent with the Directive because it added an additional clause: “For purposes of this law, such representative is deemed to be the controller.” This obligates a data controller’s appointed representative to comply with the PDPA and holds it responsible for any violations made by the data controller.

WhatsApp argued that this inconsistency between EU and Dutch law rendered the PDPA’s representative requirement null and void. The Administrative Court disagreed, citing again the Article 29 Working Party opinion WP179, which “favors a wide scope of application” of the “use of equipment” provision “to protect people and avoid legal gaps in the application of data protection principles.”

By explicitly extending liability to data controllers’ representatives, the PDPA fills one of these legal gaps—at least in the eyes of the Administrative Court. The court also cited the European Court of Justice’s “Google Spain” decision, which further endorsed a broad interpretation of the scope of Article 4 over data controllers based outside of the EU.Finally, the court explained that although a representative may be held liable for the controller’s acts under Dutch law, the two parties may contract around this requirement, agreeing between them that the controller would indemnify the representative in case a fine or penalty was issued.

- GDPR compliance premature

WhatsApp claimed that the Dutch DPA should have allowed it to take measures in anticipation of the GDPR, which requires that non-European controllers appoint only a single representative in the EU. The court rejected this argument, pointing out that WhatsApp has not appointed a representative anywhere in the EU.

- Impossibility is no excuse

WhatsApp finally argued that it was factually impossible to appoint a representative in The Netherlands, since it was not able to find a commercial party willing to act as representative and accept the risks related to that role. The court rejected that argument because the law does not include such an exemption.

The GDPR’s Representative Requirement

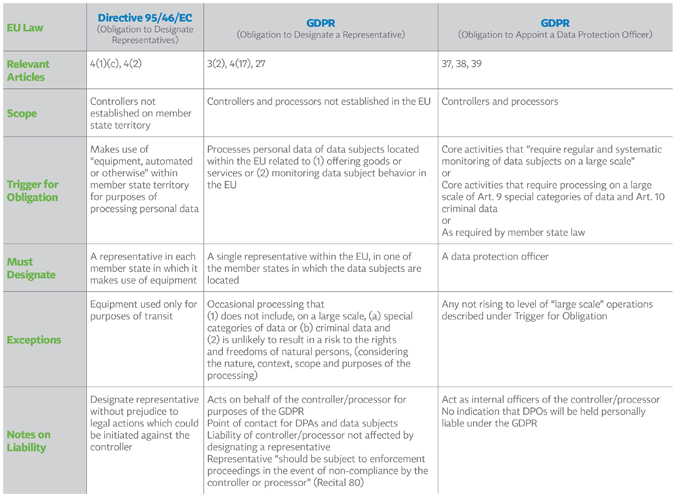

The GDPR—a massive overhaul of EU data protection standards—modifies the representative requirement in key ways: it extends the requirement to non-EU processors and requires only a single EU-based representative.

The extra-jurisdictional application of law provision under the GDPR, Article 3(2), applies EU law to “the processing of personal data of data subjects who are in the Union by a controller or processor not established in the Union, where the processing activities are related to: (a) the offering of goods or services … to such data subjects in the Union; or (b) the monitoring of their behavior as far as their behavior takes place within the Union.”

Non-EU companies that qualify under Article 3(2) must also comply with Article 27, the GDPR’s representative requirement. The GDPR, unlike the Directive, requires only a single EU-based representative which must be located in a member state where the controller’s or processor’s data subjects reside. (It is worth noting that Article 3(2) of the initial draft of the updated EU ePrivacy Regulation also includes a requirement to appoint a representative.)

- Local representatives liable for principals’ non-compliance

The person or entity acting as representative will serve as the point of contact between all 31 DPAs in the European Economic Area and the non-EU data controller or processor—and will also be subject to enforcement actions. Article 27(4) provides: “The representative shall be mandated by the controller or processor to be addressed in addition to or instead of the controller or the processor by, in particular, supervisory authorities and data subjects, on all issues related to processing, for the purposes of ensuring compliance with this Regulation.” Recital 80 further clarifies that the representative “should be subject to enforcement proceedings in the event of non-compliance by the controller or processor.”

In place of the narrow transmission exception found in the Directive, the GDPR includes an exception for companies that only occasionally engage in processing. Under Article 27(2), a controller or processor that would otherwise be required to designate a representative need not do so if its processing of personal data (1) is only occasional, (2) does not include, on a large scale, processing of the special categories of data listed in Article 9(1), (3) does not include, on a large scale, processing of personal data relating to criminal convictions under Article 10, and (4) is “unlikely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons, taking into account the nature, context, scope and purposes of the processing.”

- Representatives are not DPOs

Notably, the representative requirement is separate from the obligation under Article 37 of the GDPR to appoint a Data Protection Officer, though both roles involve data subject complaints and DPA inquiries. A company required to appoint a DPO may or may not also be required to designate an EU representative—and vice versa. For example, regardless of whether it is established in the European Union, a company with core activities that “require regular and systematic monitoring of data subjects on a large scale” must designate a DPO. The same is true of a company with core activities that require processing on a large scale of “special categories” of data.

Naturally, companies established in Europe need not appoint a European representative. However, non-European companies that fall within either of the “large scale” DPO-required categories will almost certainly exceed the “occasional processing” exception to the representative requirement and will therefore need to designate both a DPO and a local representative. In contrast, non-European companies that engage in more than occasional processing of the personal data of EU citizens related to offering goods or services or monitoring behavior, but do not meet either “large-scale” DPO requirement, will need to appoint a representative but not a DPO.

Conclusion

The Directive remains in force for the next 16 months. During this time, if DPAs in other member states agree with the Dutch DPA application of the “use of equipment” provision, any mobile app maker with users in Europe that fails to appoint representatives in each and every member state where users have downloaded the app could be subject to fines or penalties. Under the GDPR, failure to appoint a representative will be subject a maximum fine of 10 million euro or two percent of global turnover. Collecting these fines extraterritorially is a challenge under the Directive that is not yet resolved under the Regulation.

If WhatsApp’s arguments hold true, moreover, non-EU companies may struggle to find representatives willing to shoulder the risk of accepting possible liability for violations of the entities they represent.

The WhatsApp case is a wake-up call for non-EU companies and EU regulators alike. It is a reminder that even as companies push to prepare for the GDPR, the EU Directive is still in force. And it is a signal that DPAs will interpret data protection laws broadly against foreign-based entities doing business in the EU.

WhatsApp may appeal the regional Administrative Court’s decision to the Dutch State Council (the highest administrative court in the Netherlands). From there, the case could end up in the European Court of Justice. Thus, full resolution of this case may not be expected until after the GDPR goes into effect. In the meantime, the Dutch court has highlighted obligations that remain in force.

photo credit: 3D Scales of Justice via photopin (license)

![Default Article Featured Image_laptop-newspaper-global-article-090623[95].jpg](https://images.contentstack.io/v3/assets/bltd4dd5b2d705252bc/blt61f52659e86e1227/64ff207a8606a815d1c86182/laptop-newspaper-global-article-090623[95].jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=pjpg&auto=webp)