Privacy law is changing rapidly. We are seeing new laws at the state level, both general and specific. Enforcement is growing from a variety of regulators. Security breaches are in the news regularly. New technologies consistently lead to new privacy challenges. Data is being gathered in almost astonishing new ways. Countries around the world are enacting new laws. And all of this is moving toward the privacy Holy Grail in the United States — a potential, comprehensive national privacy law. This debate has been slow and fragmented — not just due to COVID-19, but also with the ongoing complexity and apparent recognition by a somewhat dysfunctional Congress that privacy law isn't an essential piece of legislation.

So what should you be watching as this debate evolves?

'Comprehensive' state laws

The national debate began to grow in intensity when California passed the California Consumer Privacy Act. The CCPA was the result of pressure from a state referendum and the product of an extremely fast legislative process (which has been followed by multiple amendments and multiple sets of regulations). All of this has meant that we have not yet seen a landslide of state laws following the California "model."

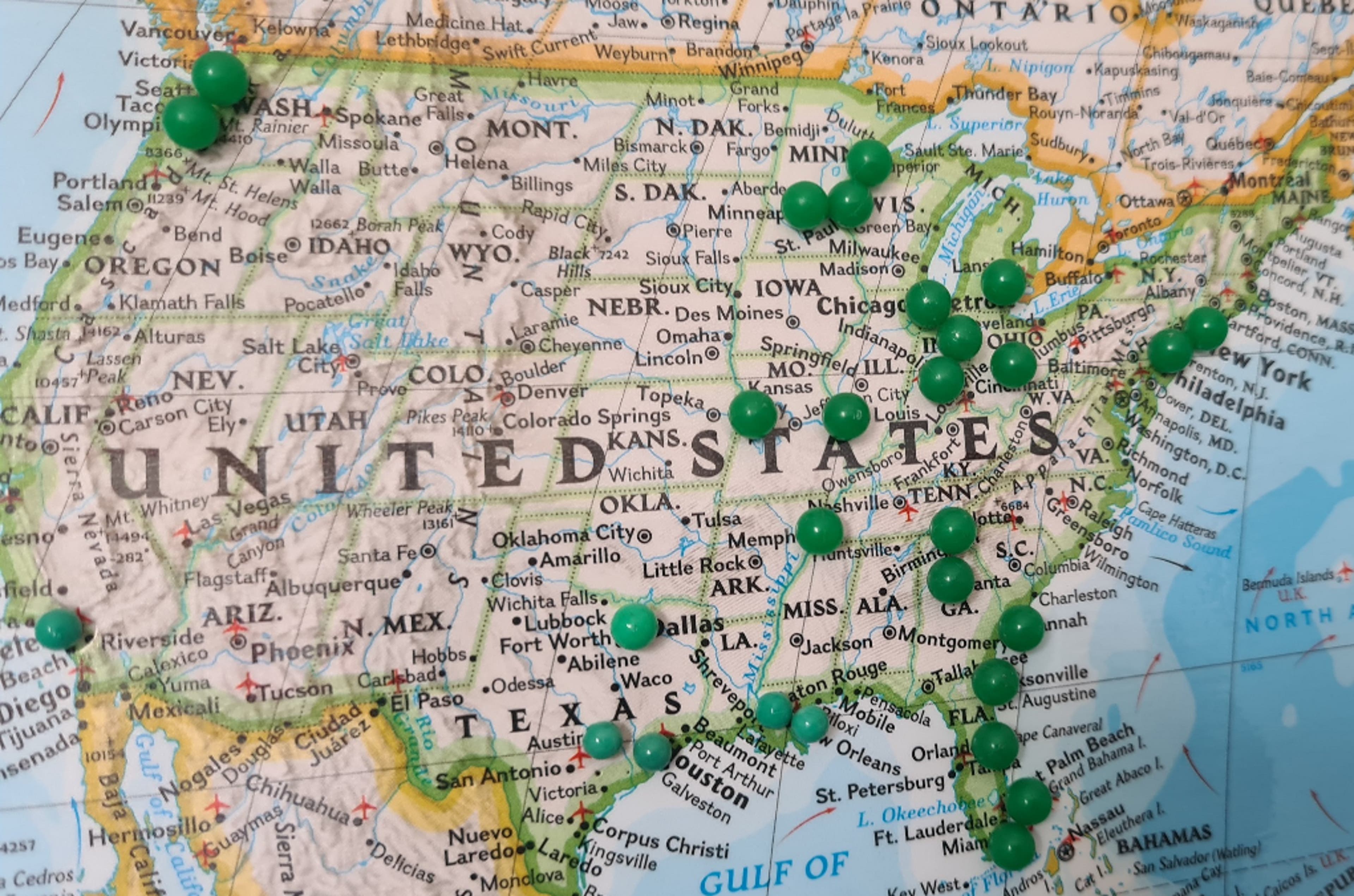

But that may be starting to change. Virginia is now the second state to pass privacy legislation with the Consumer Data Protection Act. Close to a dozen states are actively debating a state law, although debate does not mean a law will pass. Pay close attention to the states — as pressure from multiple state laws may be the most significant component of pressuring Congress to act — with this pressure at some point soon coming from industry. IAPP's J. Trevor Hughes, CIPP, coined the phrase "the Nahra Conjecture" from some of my earlier comments — that if three to five significant states pass comprehensive laws, that will put enormous pressure on the industry to come together in support of national law.

Is there a state law 'model'?

The CCPA was the result of pressure from the referendum process and the need to write and pass a law quickly without normal time for discussion, debate or meaningful review of language. Regardless of your views of the goals of the law, the result is a piece of legislation that is not well written. That is one reason why other states have not simply adopted the California law.

But states love to follow a model. When California passed the first data breach notice law, it took a few years, but then states began to pass a law that, in many states, was almost a verbatim copy of the California law. We do not see that (yet) on privacy law overall. States generally are not looking to the CCPA for copycat adoption, and these laws are hard with a number of moving parts that need to be addressed. So there isn't a current model that other states can simply adopt. Will the Virginia law, along with its non-identical twin in Washington, become such a model? Or will states continue to largely go their own way, making it somewhat more difficult to pass laws and create even more pressure on the industry when multiple states pass different laws?

What is the scope of the state laws?

The EU General Data Protection Regulation applies essentially to all data in all settings. That is a description, not a recommendation. That's not how the CCPA or Virginia's CDPA works. Those laws carve out (1) employee data; (2) most data covered by other existing laws (and in Virginia's case, even entire entities subject to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act); and (3) data held by nonprofits, along with a variety of other exemptions. As such, these laws are "comprehensive" only in the sense that they fill certain privacy gaps that exist today. Congress doesn't have to follow what these state laws are doing but watch carefully whether other state laws start to expand to cover more personal data.

The big items for a federal law

At the federal level, two topics have dominated the discussion to date: preemption and a private cause of action. The key question is whether a reasonable compromise will emerge on either of these topics, which so far have been a primary stumbling block to moving this national legislation. There certainly are possibilities. With each new state law, the baseline for a national standard grows. Will we get to a point where the baseline law is high enough that a single national standard will become a viable option? (Full disclosure: I am a big supporter of a single standard, as in general, I think it will benefit both consumers and industry, while sadly reducing somewhat the need for privacy lawyers.) Similar compromises may be available on the private cause of action. Can some package of strong enforcement options for a federal regulator coupled with the states' ability to pursue their own violations of the federal law lead to avoiding a private cause of action? Can a sufficiently narrow cause of action be developed that the industry can tolerate limited perhaps to particular categories of data or particularly egregious situations?

The breadth of the law on substance

Because these two topics have occupied most of the relevant privacy real estate in the national debate, most other issues have been given little attention. This raises the real possibility that national law may not be a good law — as the difficult challenges of privacy issues may not be given sufficient attention.

Some key issues to watch:

Will the national law address issues related to AI, algorithms and discrimination?

- Will employee data be included?

- How will the law address existing federal laws (e.g., HIPAA, GLBA, Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, etcetera)?

- Will the law apply a single standard to all personal data, or will there be different standards for different data (e.g., facial recognition, genetic information) and situations (health care versus pure retail)?

- What individual rights will be included?

- How will the "opt-in/opt-out or something else" debate be resolved?

- Will the law include national standards for data security?

- Will the law create a national standard for data breach notification?

These are really hard topics that deserve attention.

Who is managing the details?

Many of us in this industry have seen a number of previous tipping points come and go without a new law. If a series of enormous data breaches doesn't do it and the wide range of privacy "scandals" don't do it, what will? One path may be through simplicity. I can see a "simple" law, one that needs to address the topics of preemption and a private cause of action through legislation, but that leaves the rest of the tricky issues to regulation. That's one of the lessons of the HIPAA rules — where the law only defined who was coved by the rules and HHS had to draft everything else from scratch. Is that a viable option? A model that finds a compromise on the two big issues and then delegates to the Federal Trade Commission or some successor entity everything else? That likely results in some delay, that rulemaking will be the mother of all rulemakings, but we're going to need rules in any event. Maybe that's a viable path to getting this really done?

Photo by Nico Smit on Unsplash