Introducing the 'periodic table of data privacy'

Contributors:

Sophie Chase-Borthwick

NewDay

There is no business trend quite like data privacy. It is not just the speed with which it has risen to become a board-level concern, nor its near total reach as it impacts governments, businesses, customers and even wider consumers. Other business trends can say the same, including cloud computing.

What sets data privacy apart is that no other trend generates quite the same volume of popular and professional interest, inspiration, and at times, indignation.

Much of this reaction comes from the speed with which it is spreading and evolving. The data privacy movement is rapidly reaching more and more countries, industries and legislative bodies, until its hold will eventually be total. But until it is, and the same rules, rights and obligations are engrained into every manifestation of data privacy, it remains an incredibly fluid and confusing area, as we all know.

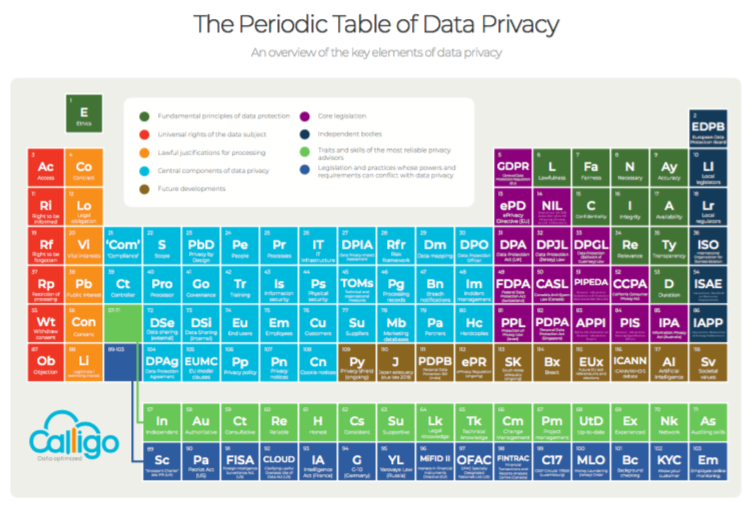

To help, we have built a Periodic Table of Data Privacy. It is designed to collate and categorize the 118 most critical “elements” of data privacy and present them in an easily digestible format.

It is an ongoing project. As the privacy world changes under our feet, we will reassess the table and update it, removing and replacing elements as appropriate.

It is also a controversial project. With space for only 118 elements, we have had to make tough decisions, simplifying some areas and even excluding some elements in favor of others. Crucially, we have tried to ignore the effects of media hype and not let the project become too GDPR-centric.

Some of our rationale for the decisions over inclusion and categorization are included below, and an even more thorough explanation is included in our blog. Take a look at the table and the reasoning behind it, and let us know what you think. We would like this to be an open project, and we are happily accepting feedback from the privacy community on how we may need to make changes. We have had some excellent input so far and have already taken some on board to create this second version. A third will not be far behind!

The categories

We have categorized the data privacy elements to mirror the traits of the categories in the original table. For example, the triangular section to the right of the scientific version is dedicated to reactive non-metals – very common elements that are the building blocks of all life, such as carbon and nitrogen and hydrogen. This was a perfect fit for the fundamental principles of data protection as without these, there could be no privacy law.

Similarly, the unknown elements in the bottom of the main section – those that are under close scientific investigation and are hopefully better understood in the future – were matched to the anticipated future developments of data privacy law. Naturally, this is the area we will update the most frequently.

Ethics

Hydrogen is the most common element in the universe. It is also the simplest and most fundamental, and on the scientific periodic table, it sits apart from all other elements. This was therefore the ideal place to put ethics.

This high status for ethics within data privacy is no exaggeration. After all, privacy legislation is the codification of what society deems to be the ethical and appropriate way in which personal data can be processed.

“Compliance”

We used some artistic licence and put compliance, element number 21, in quotes for a simple reason: It is impossible to achieve. It is a frustrating myth that continues to revolve around data privacy that compliance can be achieved. It cannot, at least not in the way that businesses commonly understand it, i.e. a one-off demonstration of adherence to certain rules.

Data privacy regulations are not designed for “single point in time” adherence. They require ongoing efforts and constant vigilance to ensure that data subjects’ rights are protected. A business’ data and processes are far too fluid for any assertion that adherence now means anything for adherence in the future, making claims of “compliance” utterly empty – and so-called certifications of compliance worthless.

EUx

The data privacy ramifications of Brexit are critical, most notably whether the UK is officially an adequate state in the eyes of the EU. But this exact scenario could be repeated in other EU countries. Italy, the Netherlands, France and others all have had robust parliamentary discussions over whether they should follow the UK and leave the EU. The inclusion of this element emphasizes the need for privacy professionals to be as up to date as possible on geopolitics and its impact on data privacy, in addition to understanding the law already in force.

Right to rectification

We have deliberately not included this. It was a hard decision, but we were constrained by the number of elements in each category. Perhaps we are being too literal, but it is regardless a very useful exercise to think in more depth about these rights and understand them better in order to work out their classifications.

Clearly this is a controversial decision, as it suggests we are prioritizing some rights over others. To be clear, we are not doing this. We are simply trying to accommodate a very complex world into only 118 items! We also felt that rectification is sufficiently addressed by accuracy and availability in the fundamental principles of data protection section for us to remove it without the underlying sentiment of the right disappearing from the table. We also needed to make room for the below.

Right to be informed

You could argue that the right to be informed is covered under transparency and other fundamental principles and so could have been excluded instead. But we wanted to include it in order to highlight an interesting observation.

This right may be universal, but the way it manifests in various legislative frameworks varies enormously. For instance, the GDPR states the right must be protected proactively through clear instructions in the privacy notices. In contrast, Canada’s PIPEDA simply states that such information should be made available, with no stipulation of it being published proactively.

We also find that our clients sometime confuse this right with that of access. For the sake of clarity, the right to be informed is concerned with understanding how data is used, while access is simply a matter of a subject being able to view what data is held.

To fully explain and articulate every choice we made in the creation of this table would take pages and pages! Most decisions were based on available space, whether there was overlap with other elements and in some particular cases, priorities. But let us know if anything in here is confusing. We are already working on updating the future developments section in light of Brazil’s imminent laws and other new announcements, and of course changes in this section will have knock-on effects on the core legislation area above it, and perhaps elsewhere.

In the meantime, give us your comments below or contact me here.