Full disclosure: Benchmarking data reveals the human error in privacy incidents

Contributors:

Mahmood Sher-Jan

CEO

RadarFirst

This article is part of an ongoing series on privacy program metrics and benchmarking for incident response management, brought to you by Radar Inc., a provider of purpose-built decision-support software designed to guide users through a consistent, defensible process for incident management and risk assessment. Find earlier installments of this serieshere.

In a previous installment of this benchmarking series, we discussed the differences in incident classification when using intent as a filter. Was the incident resulting from intentional, malicious actions? Intentional, but not malicious? Or was the incident simply unintentional and inadvertent in nature? Classifying incidents and breaches by intent serves as an important factor in assessing the severity of the incident and how an organization will determine the potential risk of harm to affected individuals.

This month, we are returning to this topic to dig deeper into incident intent classifications and how they can be further broken down into specific scenarios. To level set, looking at data from January 2017 through July 2018, we can see that the vast majority of incidents fall into one intent classification:

- Intentional, malicious intent: 0.86 percent of incidents.

- Intentional, not malicious intent: 2.78 percent of all incidents.

- Unintentional or inadvertent intent: 96.33 percent of all incidents.

The numbers show that unintentional or inadvertent incidents — those typically caused by human error rather than malicious intent such as hacking — are by far the most common.

What keeps privacy pros up at night: Incidents that are intentional and malicious in nature

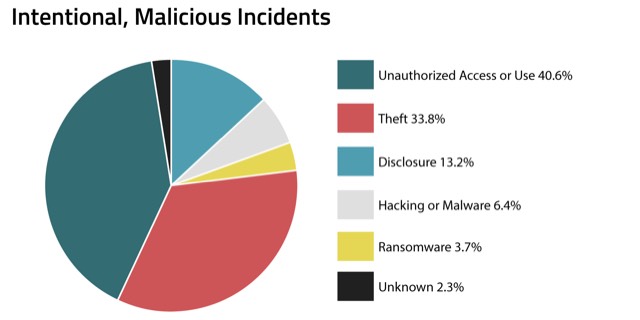

Intentional, malicious incidents are relatively rare when you look at the entire body of cases privacy professionals deal with on a daily basis. These are the incidents that result from malicious actions, such as theft, hacking or any other unauthorized access, where the intent is to cause harm to individuals.

Incidents that fall under the intentional, malicious classification are further divided into the following categories:

- Disclosure.

- Hacking or malware.

- Ransomware.

- Theft.

- Unauthorized access or use.

- Unknown.

Within RADAR incident metadata, we found that the most common type of intentional and malicious incident was unauthorized access or use of regulated data, at roughly 40 percent. An example of this type of incident would be the use of malware for capture and misuse of employee credentials by nefarious actors to gain access to sensitive customer data within an organization’s systems.

The next most common type of action, which accounts for more than one-third of intentional and malicious incidents, was theft, such as the theft of laptops or storage devices. This makes sense, as theft is commonly a malicious action, and it is assumed that the intended use of the stolen information will be for nefarious purposes.

Looking at the pie chart above, you might be surprised to see how seldom hacking, malware or ransomware figure into these incidents, given the amount of attention these types of actions get in the media. While the prospect of a hacking event or having your data ransomed certainly would make any privacy professional’s palms sweat, it’s comforting to know that in reality, these types of incidents and data breaches are exceedingly rare. Remember, while hacking, malware and ransomware might account for about 10 percent of intentional and malicious incidents, this intentional, malicious category is the least common overall, accounting for less than 1 percent of all incidents. When looking at all incidents combined, regardless of the intent or nature of the incident, these types of hacking or cyberattacks only account for 0.09 percent of the incidents reported.

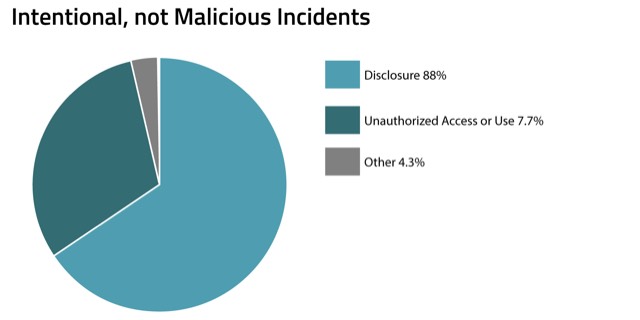

Human curiosity: Incidents that are intentional but not malicious in nature

Incidents and data breaches that are considered intentional but not malicious in nature are often the result of actions such as disclosure, unauthorized access, or employee snooping where the intent was not to use the information to cause harm. For example, a celebrity is admitted to a hospital, and hospital staff cannot contain their curiosity and look into the celebrity’s medical history.

This set of incidents accounts for less than 3 percent of all incidents overall, so it’s still a fairly uncommon occurrence. Here’s where we can further break down the types of actions that occur in this classification:

- Disclosure.

- Unauthorized access or use.

- Other (for example, improper disposal, IT incidents).

As you can see, the most common type of intentional, not malicious privacy incident is disclosure. This is a term that most privacy professionals are comfortable with, and in this classification, it typically means a passive action in which data is exposed, but the intent was not to harm the individual whose data was exposed. A very common example of this is handing off sensitive health information to a family member without a patient’s permission. The disclosure was intentional — you meant to give that family member access to that data— but it was not intended to harm the patient. Another example is forwarding an email with sensitive employee data to another employee (say, outside of the HR department) who should not have access to that information. The email was intentional, but through a misunderstanding of credentials or roles, someone got access to data that they should not have had access to.

One interesting note in this classification: When we looked at this data further broken out by industry, we noticed some differences in what is most common for the financial services industry versus health care. The health care sector assesses almost five times the number of incidents having to do with improper access or use than the financial industry. Many factors could come into play in accounting for this distinction — the nature of health information being particularly interesting (and therefore more prone to snooping), the strength of the security measures the financial sector puts into place given the strict federal oversight when it comes to financial data — and, of course, the differences between these two industries when it comes to the prevalence of paper records (which are notoriously the most at risk for improper disclosure).

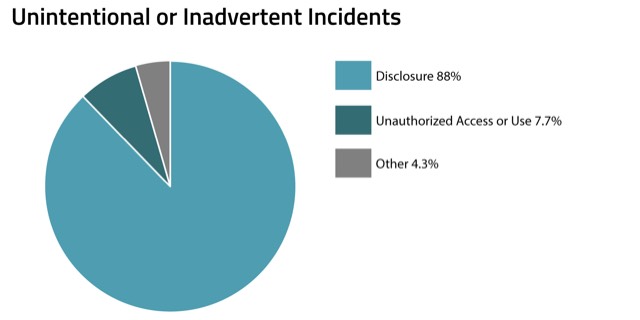

An accident waiting to happen: Incidents that are unintentional, or inadvertent in nature

As stated above, unintentional or inadvertent incidents are by far the most common in our data set, comprising more than 96 percent of all incidents that occurred. These are the incidents that result from what we think of as human error or other accidental actions such as misdirected faxes, accidental emails, unintentional posting or mailing of statements, or unintentional mailing of billing records to the wrong recipient. As you can see in the visualization below, a huge amount of incidents in this classification are disclosures.

What differentiates disclosures in this classification versus the intentional, non-malicious classification is that the intent was not to access or disclose the data in any way. This is a nuance that is important to capture when assessing if a privacy incident meets a certain threshold to be considered a data breach because it greatly impacts the severity of the incident and the potential harm to the individuals whose data has been disclosed.

Being able to tease out this level of detail can make the difference in your breach determination decision if done consistently and as part of a thorough assessment taking into account jurisdictional requirements and the risk factors involved in the incident. In this classification of incident, you might have what we would call a good faith acquisition of data, in which data was unintentionally accessed or disclosed to an unauthorized employee or agent of the covered entity and, upon discovery, the entity is able to mitigate the risk sufficiently. This type of incident classification and associated risk mitigation can be established through a compliant multifactor risk assessment, which allows the entity to demonstrate that it does not meet the threshold to be considered a data breach.

Key take-aways from the most common types of incidents when it comes to intent

While certain incident types are few and far between, it’s still critical to perform a multifactor risk assessment to determine if the incident is a data breach and requires notification to individuals and regulators. For example, improper disposal of records is a type of incident that is exceedingly rare, it only occurred in 0.02 percent of all incidents in the RADAR metadata. But incidents such as these can still be quite damaging to an organization when they occur. In fact, late last year, a New York medical practice accidentally recycled a binder that included protected health information pertaining to 2,000 patient records. This improper disposal of information was evaluated to be a data breach by the organization and resulted in having to report the breach to the Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights. This is an offense the OCR takes seriously when further investigating and has specific guidance for remaining compliant (you can read the OCR’s FAQ sheet about the disposal of protected health information here).

Another key take-away is that the things you worry about like hacking or ransomware are actually not that common. What we might call human error or fallibility is a prominent theme in the majority of privacy incidents, from pure accidents like double-stuffing financial statement envelopes with another person’s statement to plain old curiosity and misuse of credentials. Despite all the advancements in our use of technologies to protect data entrusted to our organizations, we will always have to contend with the human element. And there’s no effective cure.

But that’s why we privacy professionals continue the good fight, right? When human nature fails us, we have the processes in place to ensure incidents are detected and dealt with in an expedient, consistent and compliant manner. We promote a culture of privacy and conduct regular trainings to make sure anyone using personal data knows the proper use of that data and who to tell should it be disclosed in unintended or unauthorized ways. We set policies that protect our organizations and put guardrails on our data use. And we continue to track, measure, and improve all our processes when it comes to data breach response, from internally escalating incidents and documenting the investigation process to performing incident risk assessments to determine if individuals or regulators must be notified, including when and how.

About the metadata used in this series: Privacy is important to us, and we take every measure to protect the data of our customers and of individuals. RADAR Inc. ensures that the incident metadata we analyze is in compliance with the RADAR privacy statement,terms of use, and customer agreements. The information extracted from the platform for purposes of statistical analysis is not identifiable to any customer or data subject.

photo credit: bionicteaching via photopin