Florida privacy bill maintains PRA ahead of House floor vote

Contributors:

Joe Duball

News Editor

IAPP

The arguments around potential comprehensive state privacy legislation in the Florida Legislature boil down to a key difference between its chambers. A clear line was drawn on the private right of action during Florida's 2021 legislative session as the Florida House supported consumer redress while the Florida Senate sought to avoid it.

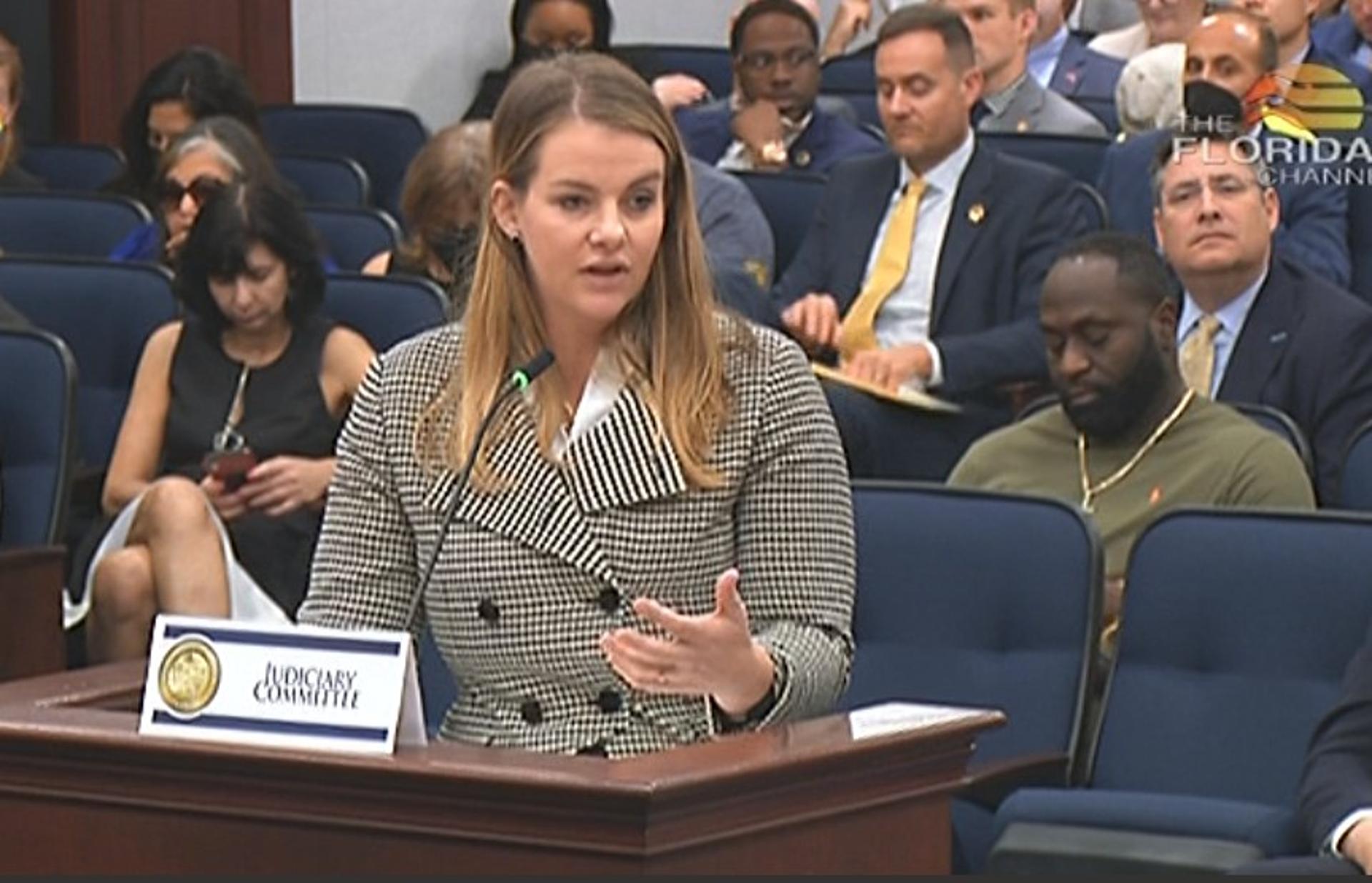

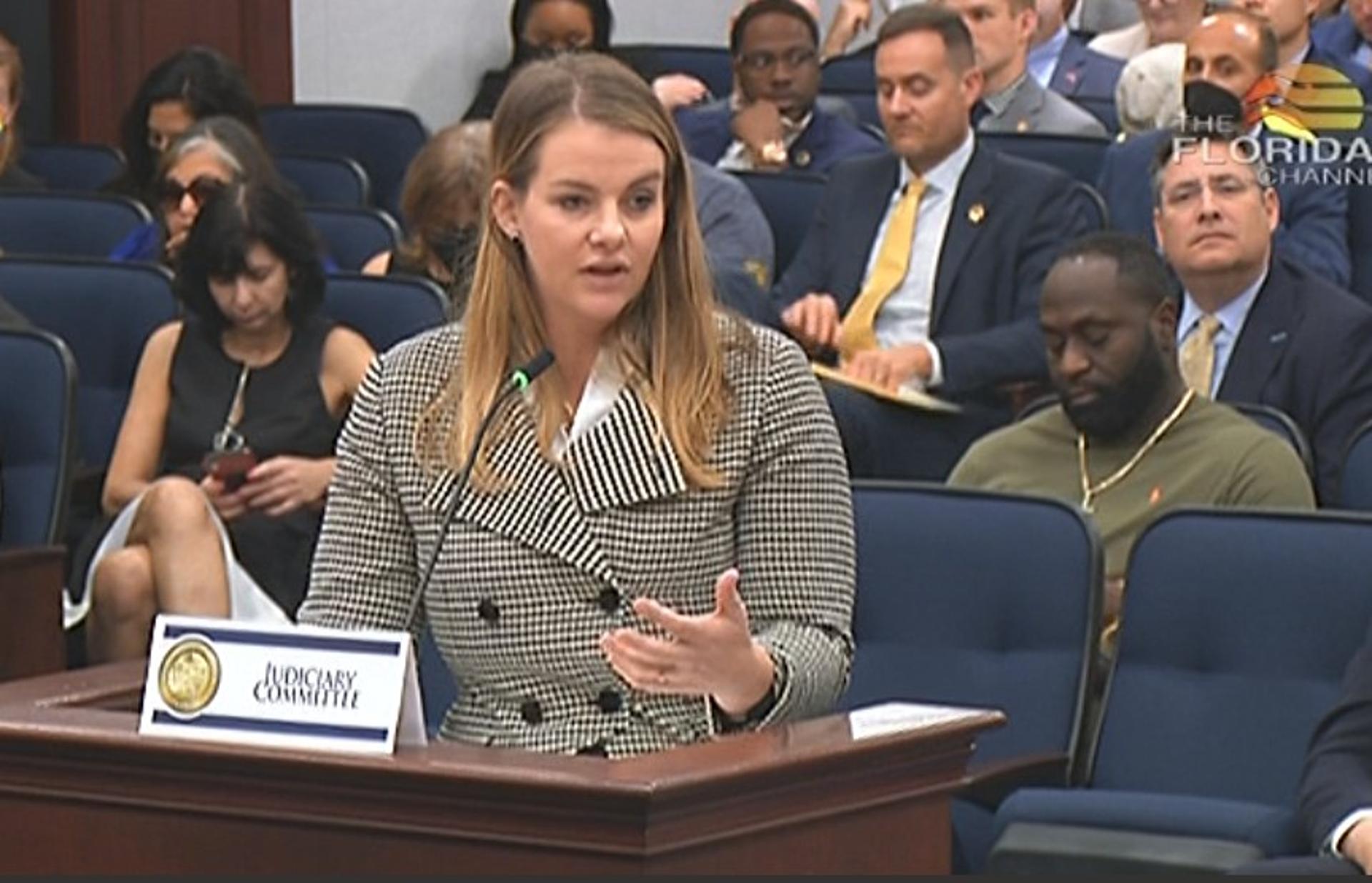

While both chambers re-introduced their versions of privacy legislation for the 2022 session, only House Bill 9 and its PRA have gained traction to this point. State Rep. Fiona McFarland, R-Fla., has carried HB 9 through two committee assignments, including the latest favorable recommendation on an amended version of the bill from the House Judiciary Committee on a 13-4 vote.

The bill has no further committee assignments and is eligible for debate and votes on the House floor. If HB 9 moves out of the House, the Senate will have a short window to act on final passage with the legislative session set to adjourn March 11.

McFarland has worked with stakeholders to tinker with the right balance dating back to last year's initial attempt to pass her bill. The latest changes approved in the strike-all adopted by the Judiciary Committee include a unique tiered approach to the PRA that hasn't been seen yet in other state privacy proposals. McFarland explained there are three levels for whether a PRA can be invoked and how it can be used:

- Level one: Businesses earning $50 million or less in annual revenue are not subject to a PRA, but attorney general enforcement is still applicable.

- Level two: A PRA can be brought for damages by businesses earning $50 million-$500 million in revenue, but no attorney fees will be awarded.

- Level three: Any business of $500 million in revenue is subject to the PRA and attorney fees can be awarded.

"Our tiered approach based on size of the company is related to the amount of harm we believe that company would be able to do," McFarland said, adding the strike-all limits baseless claims by allowing businesses to collect attorney fees if the case was dismissed with prejudice, if there was fraud on the part of the consumer or if the consumer is not a Florida resident. A statute of limitation of one year after discovery of a violation was also added.

While a PRA has long been a point of contention in privacy law discussions at the state or federal level, McFarland has tried to make its inclusion meaningful for consumers and palatable for businesses. Prior to the latest strike-all, the limited PRA McFarland had in place was limited to violations of data subject rights provided in the bill. The new wrinkle appears to work to exclude small businesses from frivolous lawsuits while dissuading bigger companies from making individuals mere pawns in a business model.

"There are two principles at war here. There's my desire to promote business, and I have a record of doing so … but that conflicts with my desire for privacy," McFarland said. "In this case, privacy has won. … This bill draws a line at the point where a company transitions from making money from me to where it starts selling me and making money off me."

The other highlight from the strike-all amendment was a change in the effective date, which was moved up to Jan. 1, 2023. McFarland considered the prior effective date of July 1, 2023, to be "somewhat of a peace offering," but noted the PRA structure, claim limits and response periods for data subject requests "reduces the liability and compliance burdens for many businesses."

Much of the opposition put forth by committee members came from Rep. Andrew Learned, D-Fla., who put forth six unsuccessful amendments that were aimed at further exemption a range of businesses from the bill. Notably, Learned's changes sought to increase threshold requirements, move responses to user opt-out requests from 48 hours to 45 days, and increase penalties to $1,000 while allowing for a 90-day cure period.

"There's a reason so many people are against this bill. For all the thousands of people that have come to the capitol this year, I haven't seen one person protesting here in favor of it," Learned said. "This bill is going to hurt Florida businesses. It's going to do so to solve a problem that existed 15 years ago. But this is the internet. We all know how it works. … Whether you are taxing them or requiring them to spend on new lawyers, you're still taxing Florida businesses."

While other states see ongoing pushes to add some form of a PRA to their bills, the battle in Florida centers on a potential right to cure in addition a right of action. It's a business-friendly tactic that all but rules out enforcement if a company is paying attention to its work flows, and Shook, Hardy & Bacon Partner Al Saikali, CIPP/E, CIPP/US, CIPT, FIP, PLS, sees a better consumer-business balance in that scenario than anything that would come from broad consumer redress.

"If you pass a right to cure for this bill, you eliminate 99% of frivolous lawsuits," Saikali said to the committee. "What will happen is you'll give the businesses that messed up, and it's going to happen because businesses make mistakes. You don't process a request in a timely way or something falls through the cracks. This says they've messed up and there's 45 days to change it or they'll be sued. I can't see a defensible position for a business if they are given 45 days and still don't cure it."

Rep. Ben Diamond, D-Fla., went even further on the discussion of balance, at one point proposing a better approach to privacy legislation should be to "get there incrementally" given "the enormity of what the bill proposes to do and the implications of it." He also suggested even if the bill passes in its current form that McFarland would "be back here next session" to offer further amendments to address emerging issues.

The arguments put forth resoundingly support shielding businesses, which McFarland doesn't seem compelled to do if it doesn't put a halt on bad privacy practices altogether.

"Suddenly, we need to have more consideration for a company to pay attention only when the courts become involved," McFarland said. "I agree that this is all policy that is better suited for the federal level or 15 years ago when data was transacted as a product and not a means to an end. But I don't want to sleep on Florida's right to privacy for another year, five years or 10 years while the federal government finds a cohesive way to address this problem."

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Submit for CPEs