The December 2007 IAPP Privacy Advisor included a job listing with Accenture for a "Privacy Compliance Analyst." This listing illustrates that nonlegal compliance roles are not new to the privacy profession. Regulations can be onerous, and organizations have relied on the help of specialists for decades. While industries like health care have dealt with heavy regulatory burdens for years, the broad applicability and enforcement of privacy laws is new. The tempo of legislation, both at the state level in the U.S. and internationally, has only added to the regulatory burden on small- and medium-sized businesses. Hence the skyrocketing demand for consultants, often cheaper and perhaps more plentiful than privacy attorneys, to provide guidance and support on regulatory compliance.

Fulfilling this demand, though, comes with risks not only to the clients but to those providing advice. Lawyers and law firms operate in a heavily regulated industry, with strict standards of professional practice to ensure client safety and confidence. Nonlawyer consultants are also, perhaps sometimes unknowingly, regulated insofar as they cannot cross the threshold into providing legal advice to clients, termed the unauthorized practice of law because they are not lawyers licensed to practice law in the client’s locale. Perhaps most at peril, with one foot on the ledge and one hanging over the edge, are lawyers operating in a nonlawyer consulting capacity who cross the threshold into providing legal advice subjecting them to sanctions for failure to apply standards of professional practice, including duties of confidentiality, escrow, conflict checking and fee sharing arrangements. This blog explores the threshold of the unauthorized practice of law and the risks of going over it.

What is the liability?

UPL raises criminal and civil liability for both licensed attorneys and nonattorney consultants. Engaging in UPL is illegal in all 50 states, though the penalties and state-specific offenses vary greatly. Most states regard UPL as a misdemeanor and a few classify it a felony. California does both by charging UPL as a felony when committed by an inactive, disbarred or former attorney. In practice, a criminal conviction of UPL is customarily punishable by up to a year in jail — the possible sentencing term could be multiple years for specific egregious or continued violations, but this is all jurisdiction-specific. Similarly, the fines imposed for UPL convictions range from hundreds to thousands of dollars. The financial risk is significantly higher, and uncapped, when one considers civil liability claims brought by clients relying on advice of the consultant. The unlicensed practitioner could be at risk for claims of breach of contract, fraud, unjust enrichment and legal malpractice. Disclaimers and insurance might not help if they are acting outside the four corners of their contract.

Licensed attorneys working on matters pertaining to the attorney’s jurisdictions may additionally be sanctioned by their bar association if they do not follow all the rules of professional conduct for client engagement. Lawyers providing consulting services outside of their jurisdiction could be additionally risking professional sanctions from their bar association for UPL. Lawyers providing nonlegal services need to clarify when they are acting in a nonlegal capacity versus as a lawyer where all the appropriate rules apply.

What line can’t (nonlawyer) consultants cross?

Definitions of what constitutes the "practice of law" vary widely. Many states do not define the term statutorily but have built up case law to craft the contours of unacceptable activities. In fact, many bar associations operate UPL committees, with some charged with determining whether certain activities constitute the practice of law and some involved in the prosecution of violators.

One definition comes from the California Code BPC § 6411(d), which states the practice of law includes "but [is] not limited to, giving any kind of advice, explanation, opinion, or recommendation to a consumer about possible legal rights, remedies, defenses, options, selection of forms, or strategies." While this definition is aimed at legal advice to consumers, more general UPL regulations in California and elsewhere cover any practice of law, even that which deals with business clients. Many hold the mistaken belief that in order to be guilty of UPL one must hold themselves out as an attorney. As with many things, the facts and circumstances are controlling, not the designation. From BPC §6126, "Any person advertising or holding himself or herself out as practicing or entitled to practice law or otherwise practicing law who is not an active licensee of the State Bar" is guilty of UPL.

The most common simplified cross-jurisdictional construct of what constitutes legal practice involves any application of the law to facts. If you’re on either side of this line, whether strictly opining about the law absent specific client facts or dealing in the client’s factual situation but not connected to law and regulations, you are probably safe. But when you mix law and facts in the same sentence, paragraph or longer narrative, you may be crossing into the practice of law. This is one reason you’ll often find attorneys speaking publicly in hypotheticals, such as "a company in such and such a situation needs to do this according to the regulation," rather than directly about a company’s activities, because the latter may create an attorney-client relationship with all the commensurate responsibilities for the attorney and rights for the client.

One justification for UPL statutes is that nonlawyers do not have these professional responsibilities or the ability to be held to account in the manner that lawyers do, and clients are not vested with the same rights they would have under the attorney-client relationship. All this, of course, on top of the possibility that the nonlawyer provides inadequate or inaccurate legal advice upon which the client relies.

What can nonlawyers do?

The foregoing does not completely prohibit nonlawyers from providing compliance-related services. There are at least four areas in which consultants can operate: teaching, tools, "form filling" and implementation. There is no prohibition on teaching or commenting on the law. We say this with a strong caveat though. Everyone remembers the fiasco of 2018 in which thousands of companies sent out emails requesting "consent" for future communications. This is just the most prominent example of bad legal advice in the privacy profession. Privacy literature, forums and training from even popular sources contain both obvious and nuanced inaccuracies. Many sources repeated the line that the EU General Data Protection Regulation required consent, leading to a cascade of ill-advised reactions in 2018. This is where the onus flips to the buyer (caveat emptor) to learn and rely on reputable, knowledgeable sources. Even lawyers get some of these things wrong when they extend into narrow specialties, of which privacy has many, many hidden niches.

Nonlawyers can provide compliance solutions, provided they do not make claims that use of such products will bring a company into compliance. Whether it's a governance, risk and compliance module, cookie banners, or consent management platforms, companies need tools that help them meet their regulatory burden. The onus is on the buyer, in consultation with counsel, to ensure the tools they employ actually satisfy their circumstances.

Two areas where consultants are valuable are in the areas of "form filing" and implementation. States have long recognized that helping someone fill out a legal form is not UPL, "so long as no advice is given" (pg 2591) (Florida Bar Rule 10-2.2). This is the exception that proves the rule and where organizations like LegalZoom fit in. For the privacy profession, this would be akin to gathering information about data flows to complete records of processing activities, data protection agreements and the like. This is not opining if the legal basis or purpose of processing were legitimate but simply rote completion of the fields based on the facts in the corporate environment.

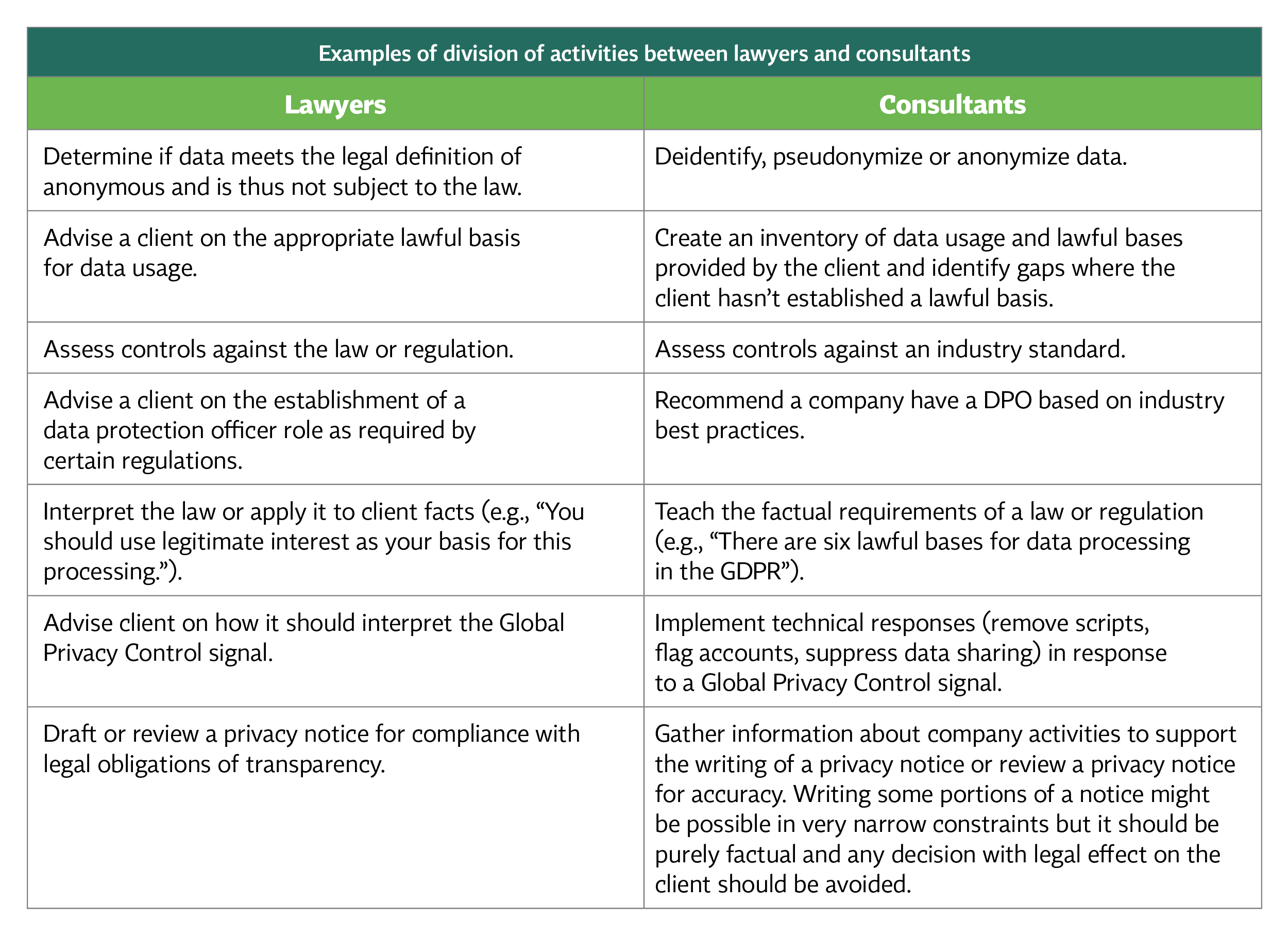

Finally, you need not be a lawyer to implement programmatic components that support compliance. A privacy engineer can help anonymize data sets, but a lawyer should be consulted as to whether excluding that data from the scope of the law meets the legal threshold. Conversely, a lawyer can set the threshold and provide it to the engineer to implement. But, in no case should the engineer be claiming it is compliant with the law or that what they’ve done brings the company into compliance.

What can consultants do to protect themselves?

While attorneys must be licensed in every state where they conduct business and follow a moral code of ethics, "consultants do not have to satisfy education or other licensing requirements; nor are they governed by enforceable codes of ethics ..." This seeming lack of guidance or accountability can leave consultants at risk for UPL claims due to their nonadherence to the rules that sums up the practice of law in their respective jurisdictions.

However, there are protections consultants can put in place to reduce exposure to UPL claims:

- When speaking with clients, state that you are not acting as an attorney.

- Draft clear contracts that outline the scope and purpose of the engagement.

- Do not provide legal opinions or apply the law to client facts.

- Be familiar with your state’s and your clients’ states’ UPL statutes and how the practice of law is defined.

- When possible, work under the direction of counsel, in house or external.

- Refer cases to counsel when a legal opinion is warranted.

- Have a clear delineation of duties between counsel and consultant.

- Include disclaimers to all documentation and invest in professional liability insurance, though, as discussed above, these safeguards are not guaranteed protections.

Consultants also bear a greater responsibility for assisting those clients who are not sophisticated users of law-related services to understand where the consultant’s representation starts and ends to avoid UPL allegations. This is in contrast with a more "sophisticated user of law-related services, such as a publicly held corporation, who may require a lesser explanation than someone unaccustomed to making distinctions between legal services and law-related services."

For those sophisticated customers with in-house or outside counsel, consultants must be aware of the challenges that could arise. While it is widely acknowledged that both "compliance and legal services are jointly responsible for an organization’s overall adherence to the law and regulatory landscape …i t is the law itself that dictates whether an organization has complied with the regulations incumbent upon it and whether its compliance program is effective." The consultant in their role as the industry expert can provide support to counsel in formulating legal advice but must defer to counsel in situations that call for advising the client and articulating a legal opinion.

Compliance consultation plays a role in any complex regulatory environment, including privacy and security. However, it’s imperative for consultants to understand the unique risks, for both clients and consultants, posed by consultation involving matters which have legal implications for clients. "Caveat venditor."

NOTE: This blog has a U.S.-centric viewpoint and may not be applicable in other parts of the world with different regulations governing the activities of lawyers and non-lawyers. As with anything you read on the Internet, this does not constitute legal advice and consider engaging competent legal counsel to advise you in this area.