We all know the EU General Data Protection Regulation has significantly affected both controllers and processors. However, a majority of articles and discussions among privacy professionals seem to be directed toward controllers, while the processor continues to be the proverbial bridesmaid. While the controller has seen the introduction of new obligations and the heightening of existing ones under GDPR, a significant shift has occurred for processors. None more so than the crystallization of what was in the pre-GDPR era a loose set of contractual obligations, into Article 28, providing a hallowed set of statutory requirements for controller to processor contracts.

In the paragraphs that follow, we touch upon some thought-provoking challenges that processors are faced with when finalizing a GDPR-compliant contract with the controller. Such challenges at times arise from some of Article 28’s contentious provisions that effectively allow both controllers and processors to argue their respective cases.

The mysterious case of unlawful instructions

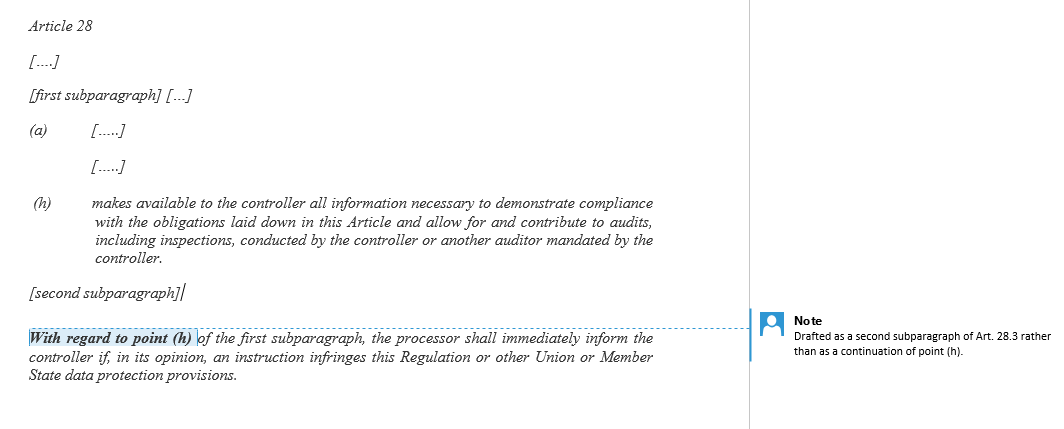

Let’s move our focus to Article 28(3). On the face of it, Article 28(3) looks like it is a straightforward list of obligations to be included in the contract between the controller and processor. However, this changes if you dive deeper. Consider the processor’s obligation to inform the controller about unlawful instructions, located as the second subparagraph of Article28(3). The location is the tricky bit.

The controller will use the location of the second subparagraph to argue that the processor’s obligation to notify the controller about unlawful instructions applies to all instructions given by the controller. However, the processor will use the explicit reference to point (h) in the second subparagraph to argue that the obligation to notify applies solely to the accountability and audit obligation in point (h). While this issue may appear academic, it effectively alters the scope of the processor’s obligation to notify and can be the difference between a breach and a non-event, which further complicates contractual negotiations.

In whose opinion?

What is also not entirely certain is whether the processor has a duty to perform legal vetting of instructions received by the controller. Given that instructions are often received by the processor in its day-to-day business operations, legal vetting of each and every instruction is simply not feasible in practice. Ultimately, it all boils down to interpreting the term "in its [processor’s] opinion." It is interesting to note that this is arguably the only provision within GDPR that gives the processor such a high discretionary power. What, then, is the intent behind this provision – that a processor cannot use "unlawfulness" of a controller’s instruction as a defense against claims? Article 82(2) would support this argument, but as for now, this remains an exasperating issue for processors.

Subprocessor trouble

Quite often, the average processor is caught between a rock and a hard place. On one hand is the problem of putting in place a proper GDPR-compliant contract with the controller – applying general principles of the GDPR and adhering to the prescribed list from Article 28(3). On the other is the challenge arising from Article 28(4) to incorporate the "same obligations" agreed with the controller in the agreement with the subprocessor, the one usually hesitant to accept the same obligations given differences in financials and risk profile.

The problem is accentuated when dealing with large, enterprise-level subprocessors who service multiple customers and offer "click-wrap" standard data protection terms to all customers, via cloud service providers. There is no easy fix, and generally, the processor often either requests the subprocessor to consider changes to their standard data protection terms or attempts to "flow-up" the subprocessor’s data protection terms to its customers. Another alternative, which is arguably the worst for processors, is to absorb the contractual gaps, risking both contractual and statutory breach. This invariably leads to long-drawn, protracted negotiations with both the controller and the subprocessor, resulting in business delays and interruptions.

Conflict of laws

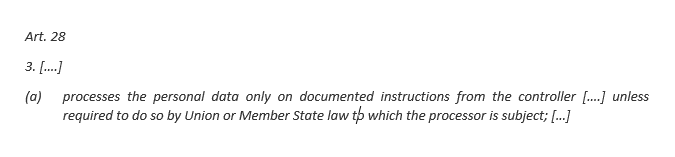

The processor is obliged to process the controller’s data only on documented instructions, unless processing is required by a European Union or member state law. While it is understandable that the GDPR only takes into consideration laws applicable within the EU, this is a potentially significant legal risk for non-EU processors who may have non-EU statutory obligations with regards to personal data. To factor in this scenario, a processor may argue for a broader interpretation of subparagraph 3(a) of Article 28.

The processor may contend that the exemption applies to any law to which the processor is subject to. The controller will predictably object, arguing that this may constitute a breach of the GDPR. This issue would ultimately be decided by “conflict of law” rules, which essentially leads to the processor not having a definitive answer.

Unlimited liability trap

Another issue is liability. Being one of the most contentious aspects in a commercial negotiation, it is hardly a surprise to anyone that liability is an issue. GDPR-related liabilities and fines have added another layer to that. Controllers continue to push for unlimited liability for breach of data protection obligations. However, processors are now wary of accepting this.

Furthermore, the market practice of accepting unlimited liability when it comes to breach of confidentiality obligations makes the issue even murkier. The pertinent question is: Isn’t all personal data confidential? In fact, in most transactions, personal data enjoys the highest degree of confidentiality, and definitions of "confidential information" invariably include "personal data." One could, therefore, argue that by accepting unlimited liability for breach of confidentiality, the processor is, by implication, accepting unlimited liability for a breach relating to personal data. This is an issue that must be considered carefully when negotiating a contract. A potential solution could be to explicitly carve out data protection liability from confidentiality in order to avoid accepting unlimited liability through the back door.

Most organizations want to have robust and effective contracts that comply with the GDPR in letter and spirit, but it is only natural for processors to think about balancing compliance with their commercial and business interests. In practice, negotiations of commercial contracts are already tipped in favor of controllers, who would mostly be in the position of a "customer" and can, therefore, be in the driver's seat and sway negotiations their way.

The GDPR allows for just enough wiggle room for processors to be able to put forth solid arguments to advance their case. The statutory reliefs under Article 82(2) and (3) could prove to be the processor’s resident superheroes. While awaiting the answers that the future holds, processors should use currently available know-how to create data protection terms which comply with the GDPR and at the same time, enable a business to run smoothly.

While there are no ready-made solutions to hand, hopefully, clarity will come with time. For issues like subprocessor flow-down terms and the lack of clarity on unlawful instructions, we need further guidance from the likes of the European Data Protection Board and the data protection authorities. Processors will need to closely monitor judgments and judicial opinions on litigious issues, such as conflict of laws and GDPR applicability. It is important to remember, however, that public bodies may not always provide industry-specific advice, and therefore, it is controllers and processors themselves that will have their say on shaping a new realm.

Watch this space.