State views on proposed ADPPA preemption come into focus

Contributors:

Joe Duball

News Editor

IAPP

Lines have been drawn for some time now regarding where U.S. lawmakers are willing to go with preemption provisions in the proposed American Data Privacy and Protection Act. Those lines were defined back in 2019, and lawmakers' willingness to cross them for a compromise is still a tall task neither Democrats or Republicans have fully come around on.

The current case in point is the U.S. House's California delegation, whose reluctance to allow the proposed ADPPA to preempt the California Consumer Privacy Act and California Privacy Rights Act is stymieing the federal bill's passage out of the House. In her statement opposing the current ADPPA preemption framework, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., said California "leads the nation not only in innovation, but also in consumer protection" and deemed it crucial that the state "continues offering and enforcing the nation’s strongest privacy rights."

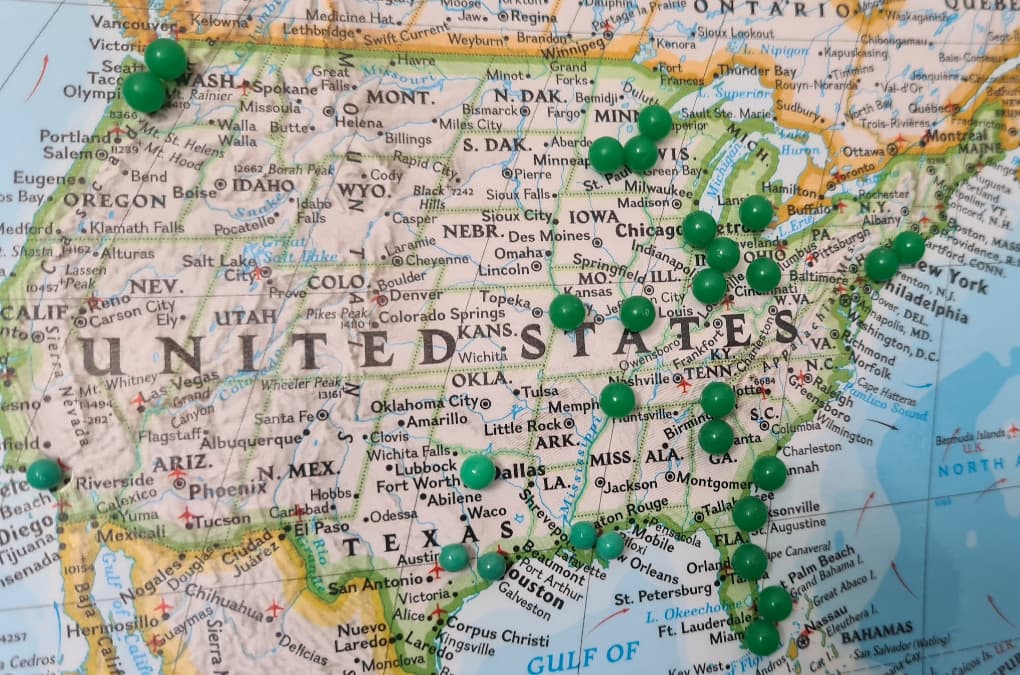

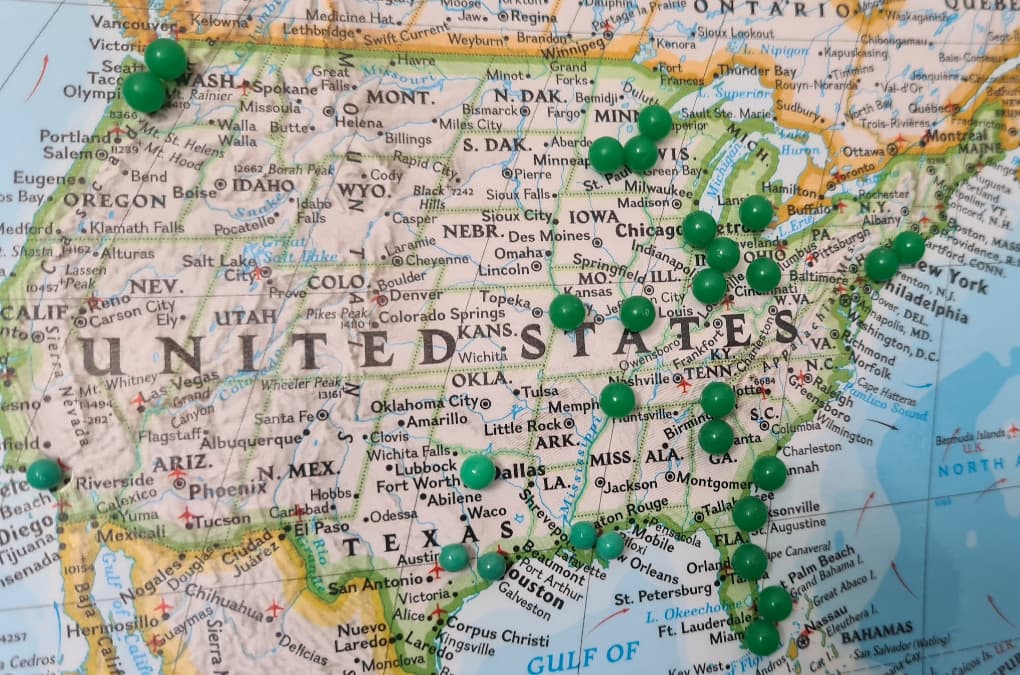

While California's concerns are warranted, the other side of the argument begs the question about what is best for the other 49 states. Colorado, Connecticut, Utah and Virginia have comprehensive state privacy laws of their own coming online in the next year, all of which would likely be affected in some shape by ADPPA preemption. Then there are the states that would address privacy with passage of the ADPPA and implement a standard they otherwise wouldn't have.

And though some state views may align with California on preemption and the ADPPA's perceived gaps, opinions are not homogenous.

Congressional action welcomed, but worries remain

The state lawmakers who introduced comprehensive privacy legislation in recent years did so due in large part to federal inaction. They said as much when advocating for their bills in committee hearings.

"I agree that this is all policy that is better suited for the federal level or 15 years ago when data was transacted as a product and not a means to an end. But I don't want to sleep on Florida's right to privacy for another year, five years or 10 years while the federal government finds a cohesive way to address this problem," State Rep. Fiona McFarland, R-Fla., said during a Florida House committee hearing on her comprehensive privacy bill in February. McFarland's House Bill 9 was one of the many proposals that did not make it to the finish line in 2022, while Connecticut and Utah did finalize legislation.

Whether states clamoring with their own bills pushed U.S. Congress at all with the ADPPA is unknown, but the release of the federal proposal's discussion draft in June and the legislative process since shows that Congress is trying.

That's a positive step regardless of influence or incentive, according to state Sen. James Maroney, D-Conn., who was the lead sponsor of Connecticut's privacy law.

"From a lot of perspectives, a federal bill would be the best course of action," Maroney told The Privacy Advisor, noting he has focused his attention on the ADPPA's provisions for children's privacy and algorithmic assessments in hopes of applying those provisions to Connecticut's law in some fashion. "If it's as strong or stronger (than the Connecticut bill) then I'll really just feel like our work helped contribute to that and pushed them along … That's better for the overall privacy movement to have the one federal bill."

Maroney stopped short of saying whether the current federal bill and its preemption are worth moving forward, calling back instead to California lawmakers' proposal for a federal floor from which states can build. He said setting a floor is the approach most states have gone with already, knowing they need to establish legislation that will likely require amendments based off emerging technologies and trends.

State Sen. Reuven Carlyle, D-Wash., was unsuccessful in passing the Washington Privacy Act the last four years, but the bones of his original framework are the basis for the privacy laws passed in Colorado, Connecticut, Utah and Virginia. Each of those laws may need to evolve with technology and circumstances, meaning a federal law must adapt via its own provisions or continue to allow states to act.

"We need to ensure the floor of the protections the federal government might establish are genuine, meaningful and compelling, while the rights and obligations are serious to meet the moment of this historic era of data," Carlyle told The Privacy Advisor. "I do have a sensitivity to a patchwork between states. But Congress can't have it both ways where it sets a low floor and then prohibits states from innovating. Different global platforms approach these issues in different ways. We have to evolve."

Addressing the stalemate

The existing ADPPA preemption proposal was termed as "carefully crafted" by U.S. House Committee on Energy and Commerce Chair Frank Pallone, D-N.J. The description mostly stems from the inclusion of unique preservation clauses for state legislation related to facial recognition — specifically, the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act and Genetic Information Privacy Act — and the private right of action for data breaches under the CCPA, in addition to more broad carveouts.

"There's a little bit of an institutional arrogance that dominates the issue of preemption. Where you stand depends upon where you sit," Carlyle said, explaining a rare hesitation each level of government has to invoke preemption — whether it be federal law supplanting state law or state law overtaking local law.

Carlyle's initial pause with preemption had more to do with the expectation that Congress could not strike the right tune for data subject rights and business requirements. But the ADPPA brought a surprise resolution for Carlyle. He said the bill's rights and requirements are "admittedly a bit stronger than I expected they would be able to come up with" and lawmakers "can't discount and walk away from it."

The hang-up for Carlyle now is the legislative floor-versus-ceiling debate and the lack of trust in the federal government to update legislation after passage before it becomes obsolete in a matter of a few years.

The ADPPA is "not going to be tinkered with in a meaningful way for a decade or generation. We are living with it because of the general dynamic for how Congress works," Carlyle said.

Sunsetting preemption after a certain number of years could appease federal and state lawmakers. While it wouldn't be immediate, a sunset creates the highly sought-after floor and state-level intervention abilities.

"That may be a form of a compromise. I don't know what the timeframe is because of the ability for technology to change much faster than the ability to regulate it," Connecticut's Maroney said. "Ten years would be too long to not allow action on new things that come up. In some ways I feel like five years is too long. I do see how it'd be good for companies to all be able to come into compliance and have that certainty for a few years."

But even the soft landing of a sunset brings opposition.

State Rep. Collin Walke, D-Okla., CIPP/US, CIPM, told The Privacy Advisor the goal should be to pick a direction: Choose between the network of state laws with states handling matters at their pace or full federal preemption.

"I have to ask, what would be the point (with a preemption sunset)?" said Walke, whose proposed Oklahoma Computer Data Privacy Act passed the Oklahoma House two years in a row before dying in the Senate. "Create consistency and homogeneity — both good things — only to create balkanization down the road? I believe that the better route would be to set a federal floor, not a ceiling."

The California dilemma

Public pushback on preemption at the state level has come primarily from California. The one exception was a letter to Congress from 11 state attorneys general, led by California Attorney General Rob Bonta, explaining how those states "demonstrated that we are up to the task when it comes to privacy protection."

California has coordinated opposition to preemption. California members of the U.S. House made their opposition clear in committee while Gov. Gavin Newsom, D-Calif., California Privacy Protection Agency Executive Director Ashkan Soltani and California state lawmakers all offered their concerns for Pelosi's consideration.

Other states have not been as public with their support or opposition to preemption. But even if there were more states chiming in, California's argument would likely remain siloed from other states. A prevailing view within the privacy community is the Washington Privacy Act model adopted in some fashion by each of the four non-California states brings a form of consistency and unification. Those four laws run parallel with the CCPA in some spots, but California's law has its own unique touches that make it an outlier.

"There were a lot of efforts to maintain some form of interoperability and having a federal bill would ensure that. It doesn't negate the work we've done," Maroney said. "There are more residents already subject to California's privacy laws. We're also talking about one of the largest economies in the world with that state, so they do have the ability to drive more. Ultimately there is going to have to be compromise."

For states like Oklahoma and others without legislation on the books, Walke said it isn't ideal for California to be holding up federal legislation to preserve its state law at the cost of privacy rights and protections to all U.S. residents.

"For the roughly four million Oklahomans who have no data privacy rights, the ADPPA at least provides a baseline of rights that don’t currently exist," Walke said. "Watch almost any debate in the Oklahoma House of Representatives and you’ll see legislators say, 'This bill isn’t perfect. No bill we ever pass is.' That’s my attitude toward the CCPA-versus-ADPPA debate. Don’t deprive me of my rights simply because you don’t get 100% of what you want."

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Submit for CPEs