Examining the President’s Proposed National Data Breach Notification Standard Against Existing Legislation

Contributors:

Patricia Bailin

Head of Data Policy

Airbyte

The proposed bill would require companies to notify consumers within 30 days of discovering a security breach [Sec. 101(c)], and in some cases, also notify a federal entity designated by the Secretary of Homeland Security [Sec. 106(a)]. The bill defines a “security breach” as unauthorized acquisition of or access to sensitive personally identifiable information, and it defines “sensitive personally identifiable information” as an individual’s name and two additional data elements together or any one of several unique data elements on their own, such as biometric data or a government issued ID number [Definitions]. It requires direct notification of affected individuals and media notice if the number of affected individuals in any one state exceeds 5,000 [Sec. 103]. It further specifies the information that should be communicated in the notifications to all affected individuals [Sec. 104]. The bill gives rulemaking authority to the FTC and enforcement authority to the FTC and state attorneys general [Sec. 106(b), 107, 108] and contains a preemption provision to ensure the bill will “supersede any provision of the law of any State, or political subdivision thereof, relating to notification by a business entity engaged in interstate commerce of a security breach of computerized data” [Sec. 109].

Though the proposed bill has earned support from industry and consumer protection groups alike for its effort to simplify the existing system of notification rules, some privacy advocates remain concerned about the bill’s preemption provision. They contend that uniformity should not be achieved at the expense of strong consumer privacy protections, fearing that preemption would effectively weakenconsumer protections in places that currently have stricter breach notification requirements than the proposed federal standard. Some advocates have even suggested that preemption could prevent local governments from developing non-breach-related data security rules.

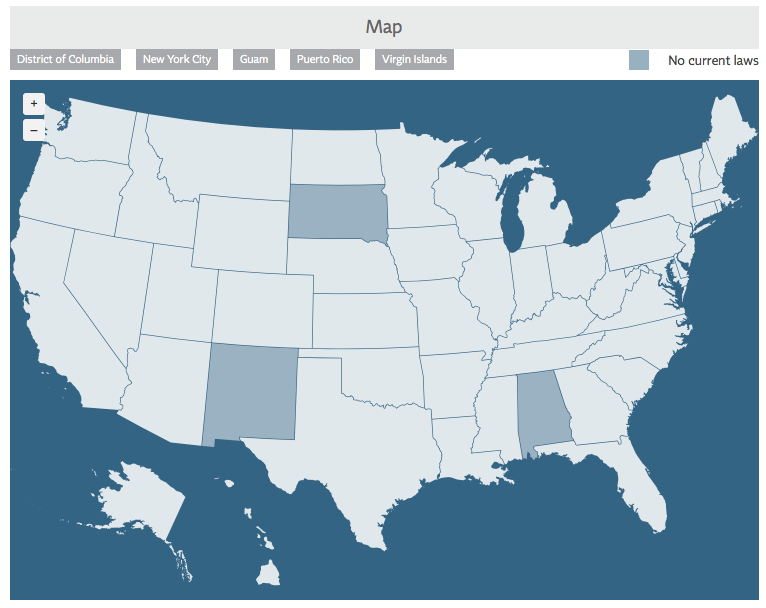

According to Westin Research Center analysis, these fears are overstated for two reasons: First, while the preemption provision achieves uniformity across states and territories with respect to breach notification, it is also limited in scope – narrowly tailored to address only breach notification requirements without prohibiting governments from innovating in other security areas and continuing to regulate their state and local agencies. Second, while the bill establishes a ceiling, a necessary byproduct of a harmonized standard, it does not effectively weaken the existing system, since in most critical areas, few states or territories actually apply stricter requirements. In fact, by creating uniformity in accordance with the majority of the most stringent existing standards, the President’s proposed bill ensures that as a general matter, residents of all states and territories (including the three states that currently have no breach notification requirements and the many whose provisions are significantly weaker) are provided the same protections available to residents with the strictest provisions.

At the same time, the bill’s elimination of a private right of action may restrict a steadily growing avenue for individual redress and private enforcement through litigation and class actions.

Defining “Security Breach” and “Personal Information”

The proposed bill defines a security breach as a compromise or loss of computerized data resulting in “the unauthorized acquisition of sensitive personally identifiable information [SPII]” or “access to [SPII] that is for an unauthorized purpose, or in excess of authorization.” This definition is narrower in scope than a few state laws with regard to the format of the data, but covers a greater range of security events than the existing system. Specifically, the language of the proposed bill covers only computerized data, not information in other formats as at least three states cover, but it applies to unauthorized access to and acquisition of data, while most laws define a breach as only the latter.

In defining the types of compromised data that trigger notification requirements, the proposed bill covers a greater range than its current counterparts. Existing laws generally define personal information as an individual’s name plus an additional sensitive data element like a social security number, credit card number or password. The proposed bill goes further to define SPII in two ways: the first as electronic or digital information that includes an individual’s name and two of the following: home address or telephone number, mother’s maiden name or full date of birth; the second as one of several data elements that constitute SPII on their own:

- a government-issued ID number (such as a SSN, Driver’s License number or passport number)

- any unique biometric data

- a unique account identifier (such as a credit card number, bank account number, routing code or user name)

- a username or email address in addition to a password or answer to a security question that would permit access to an online account.

Under the President’s bill, none of these data elements have to be connected to a consumer’s name in order to trigger breach notification requirements. This constitutes a significant expansion of coverage under existing laws. Though a few do not require names to be connected to special categories of sensitive data like SSN (Indiana) or credit card numbers (Kansas) in order to qualify as personal information, the vast majority of existing laws limit personal information to data connected with a first and last name and none identifies as many categories of SPII as the President’s proposed bill. Moreover, the bill notes that under the rule promulgated under section 553 of title 5 of the U.S. Code, the FTC may amend the definition of SPII “to the extent that such amendment will not unreasonably impede interstate commerce, and will accomplish the [bill’s intended] purposes.” With the FTC empowered to modify the elements that constitute SPII, the bill has a strong chance of remaining up-to-date with data trends over time.

Despite the wider range of data sets it covers, however, the proposed bill expressly omits health and medical information. At least nine states and Puerto Rico include this type of data in their definitions of personal information covered by their breach notification statutes. Though it is possible the administration was attempting to preserve the autonomy of federal statutes already governing health data, the omission of health and medical data from the definition of SPII complicates the interplay with certain existing laws, as discussed in the following section.

Defining “Covered Entities”

The proposed bill applies to business entities (for profit and non-profit) that “use, access, transmit, store, dispose of or collect SPII about more than 10,000 individuals during any 12-month period.” It is highly limiting language, arguably setting a lower standard than that under any of the existing laws, which do not distinguish a covered entity by its number of customer records. By setting a floor of 10,000 individuals, the bill effectively exempts from breach notification requirements smaller entities collecting consumer information that might otherwise have been covered under the existing system, such as small businesses and individuals who collect fewer than 10,000 records annually.

The bill addresses the question of allocation of notification responsibility between a breached entity and an owner/licensee of the breached information, in case they are different – an issue inconsistently resolved among existing laws. In the event of a breach, the proposed bill obligates the breached entity to notify affected individuals regardless of whether it owns or licenses the data. If the breached entity does not own or license the data, it is required to notify the data owner or licensee, although such notification does not release it from its obligation to notify affected individuals. The proposed bill clarifies, however, that if the owner or licensee of the data provides the notification itself, then the breached entity is released from its obligation to notify. In addition, notification obligations can be contractually transferred to another party, and the proposed bill does not prevent or nullify such an agreement.

The proposed bill carves out an exemption for entities and vendors covered by the HITECH Act, which contains its own breach notification mandate. Some current laws also contain an exemption for HIPAA (and an exemption for entities covered by the GLBA). Still, the majority do not provide such an exemption and in some cases impose stricter requirements for HITECH covered entities than HITECH itself. Because HITECH exempts from its preemption provision laws with more stringent requirements, these stricter standards remain effective. In contrast, the proposed bill contains no such exemption for stricter state provisions. Commentators have suggested, therefore, that in the case of health data handled by entities covered by HITECH, the lack of an exemption from the bill’s preemption provision means that while a state’s existing breach notification law with regard to covered health entities is not overridden by HITECH (which exempts stricter state laws from preemption), it would be overridden by the President’s proposed bill. In other words, critics argue that the bill’s broad preemption provision may dilute consumer protection in states whose breach notification laws cover health data and contain stricter protections than those under HITECH.

Upon closer reading of the statutory language, however, it becomes clear that this criticism is unfounded. Section 111 of the bill specifically states that, “Nothing in this Act shall apply to business entities to the extent that they act as covered entities…subject to the [HITECH] Act.” This means that for HITECH covered entities, the bill’s preemption provision [Sec. 109] does not apply. Consequently, stricter state laws, which survive HITECH, remain in effect with regard to such entities. Moreover, even states or territories that do not currently impose stricter standards on such covered entities could craft new legislation without conflicting with the President’s proposed uniform standard.

It is worth noting that while the interplay between the President’s bill, HITECH and existing laws does not create a statutory loophole, the combination of the HITECH exclusion with the omission of health data from the definition of SPII does. Over the past few years, an entire industry, which is not covered by HITECH, has emerged around the collection and handling of consumers’ health and fitness data through a plethora of websites, apps and wearable devices. The wearable technology industry already provides numerous devices for collecting, recording and assessing personal health information from millions of individuals. While a breach of this data could certainly be harmful to consumers, companies would arguably fall outside the remit of both the President’s bill (due to the definition of SPII) and the HITECH Act – a gap that does not appear in the existing state system. Here, the proposed bill’s preemption would apply, meaning that stricter state laws would be set aside. Remedying this gap would require either the addition of health and medical data to the definition of SPII or an adjustment to the preemption provision of the proposed bill such that state laws relating to data sets outside the scope of the proposed legislation remain unaffected.

Defining “Timeliness of Notification”

As in existing laws, the proposed bill addresses two types of notifications: one to law enforcement and the other to affected individuals. The proposed bill requires covered businesses to notify a federal entity designated by the Secretary of Homeland Security so that it can alert relevant law enforcement agencies in the event of a security breach. This notification must take place “as promptly as possible,” which the bill defines as within 72 hours before notifying individuals or within 10 days of the discovery of the incident, whichever comes first. By mandating a timeframe for notification to law enforcement, the proposed bill strengthens the existing system; Puerto Rico has the same 10-day requirement, but no other state or territory sets a timeframe for notifying law enforcement. Three states impose a stricter timeframe for notifying the state Attorney General’s office in situations where a state agency is breached and/or medical information is lost, but these situations are irrelevant given the scope of the proposed bill.

The bill states that notifications to individuals “shall be made without unreasonable delay following the discovery by the business entity of a security breach”; it defines unreasonable delay as exceeding 30 days unless necessary for law enforcement or where the business entity can demonstrate to the FTC that additional time is needed. On the one hand, the 30-day maximum is more specific than under existing laws. Maine (seven business days after law enforcement has authorized notification), Florida (30 days) and Wisconsin, Ohio and Vermont (45 days) are the five states that cap the reasonable timeframe. Most state laws employ the language “within the most expedient time possible and without unreasonable delay, consistent with any measures necessary to determine the scope of the breach and restore the … the data system.”

On the other hand, by specifying a 30-day maximum rule as opposed to relying on a standard, the proposed bill may unintentionally offer businesses a cushion to delay notifications in the event that in fact they are able to notify consumers sooner but choose to wait for the expiration of the 30-day window. This lowers the bar compared to state laws that demand reasonable expediency. At the same time, however, it is arguable that by capping the amount of “reasonable” time, the bill limits the flexibility companies have to respond to the breach. Some businesses and industry groups, in fact, have already suggested that 30 days is too short a timeframe to work through the procedures necessary to respond properly to a breach. They would likely interpret state rules mandating the most expedient time possible and without unreasonable delay as longer than 30 days. In this context, the 30-day maximum offered by the proposed bill might actually tighten the timing requirement compared to state laws, since it leaves less room for interpretation. Of course, if businesses need more than 30 days to notify individuals, they can request an extension from the FTC, which has the authority to grant extensions in up to 30-day increments.

There are three exemptions to the bill’s notification obligations:

- If the U.S. Secret Service or Federal Bureau of Investigation determines that notification would reveal sensitive national security information or impede the ability of law enforcement to conduct an investigation, then notification may be delayed or prohibited. This provision exists in state laws as well.

- Entities that conduct a risk assessment in accordance with information security standards and conclude that no reasonable risk of harm to the affected individuals will occur as a result of the breach are exempt from notification. The results of the risk assessment must be submitted in writing to the FTC no later than 30 days after the breach unless the FTC grants the entity an extension.

The majority of existing laws include a similar “risk of harm” qualifier. However, the difference between the phrasing of this exemption in the proposed bill and many of the current laws suggests a difference in the default trigger. Current laws tend to provide: if there is risk of harm, then notification is required; the proposed bill provides: notification is required, unless there is no risk of harm. The difference in the underlying assumptions – the current laws assume no notification unless risk of harm; the bill assumes notification unless no risk of harm – reflects a stricter standard under the proposed bill. The bill implies that a breached entity should immediately prepare notifications for individuals upon discovery of the incident, even if a risk assessment is being conducted in tandem with those preparations. Many current laws seem to suggest that businesses may conduct their risk assessment prior to preparations for notifying individuals, which could ostensibly extend the timeline of a breach notification and increase the risk of harm to consumers. Moreover, in a few states, breached entities do not need official approval for their risk assessment from any authority, a serious lack of oversight that the proposed bill remedies through its requirement that the FTC review and approve a breached entity’s risk assessment report before it applies an exemption.

- The third notification exemption applies only in the event of unauthorized access to credit card numbers or their security codes and only to business entities participating in or utilizing a security program that prevents financial fraud. A program that prevents financial fraud is defined as one that effectively blocks the use of SPII for unauthorized transactions before they are charged to the affected individual’s account and provides for notice to affected individuals in the event that the program is unable to prevent fraudulent or unauthorized transactions from occurring after a breach. Some states have a similar exemption provision, though with less stringent program specifications.

Defining the notification

The proposed bill requires a breached entity to provide notification to all individuals affected by or at risk of being affected by the breach. Entities may notify individuals by mail, telephone or email if the individual consented to receive electronic communications. If the number of affected individuals in any given state exceeds 5,000, the entity must notify individuals through “media reasonably calculated to reach [them].” All existing laws require direct notification of individuals, although the acceptable method of notification varies. Some states and the territories also allow for notification through the media, and – like the proposed bill – this is usually acceptable only in certain circumstances, such as when the entity does not have contact information for the individuals, the number of affected individuals is large or the cost of notifying affected individuals directly would exceed a specified dollar amount.

Like many current laws, the proposed bill mandates basic content requirements for the notification. At a minimum, the notification must include a description of the categories of SPII compromised in the breach; a toll-free number to reach the entity or its representative and to learn what types of SPII the entity maintained about the affected individual, and contact information for the major credit reporting agencies and the FTC. The bill also specifies that the notification must identify “the business entity that has a direct business relationship with the individual,” regardless of whether that business entity or a designated third party provides the notification. A few laws currently require other or additional information to be conveyed in the notification, but the message remains the same under both the existing system and the proposed federal standard.

Notably, the proposed bill permits a state to require additional notification about victim protection assistance provided in that state. This is the sole exception to the bill’s strict preemption clause. It means that states currently offering victim protection assistance (and states that might desire to offer it in the future) may continue to provide such services to their residents.

As in many existing laws, the proposed bill requires business entities to notify all consumer reporting agencies if more than 5,000 individuals were affected by the breach. At least 23 states and D.C. possess a similar requirement, though the majority of laws have a lower threshold of 1,000 individuals. Only New York (5,000 individuals), Georgia and Texas (10,000 individuals) have a threshold greater than 1,000. Given that these laws cover only residents of single locations while the federal legislation applies nationally, this disparity is understandable.

Defining the enforcement authority

The proposed bill designates enforcement authority to the FTC and state attorneys general. The FTC would enforce the bill under its Section 5 authority. State attorneys general would be permitted to bring a civil action on behalf of their state’s residents affected by the breach (after providing notice to the FTC and the U.S. Attorney General) and to request, among other things, civil penalties of up to $1,000 per day per individual affected, with a maximum penalty of $1 million per violation, unless the breach is deemed willful or intentional.

Although states could collect civil penalties on behalf of their residents, it is unclear whether affected residents would receive reimbursement. Importantly, unlike the laws of 13 states, D.C., Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, the proposed bill does not provide for a private right of action for individuals impacted by failure of a breached company to provide timely notification. Critics suggest that this restriction is a serious flaw, since by preempting current laws without providing individuals with an alternative remedy, the bill would weaken the existing framework.

To be sure, some of the laws that currently allow individuals to make private claims also impose various limitations. Affected individuals in Massachusetts, for example, must wait for the state Attorney General to find the breached company in violation of the law before they may file a suit of their own. Moreover, while a provision for a private right of action appears in some federal privacy statutes, such as the CAN-SPAM Act or the FCRA, other important federal privacy laws, including COPPA, FERPA, GLBA and HIPAA, do not provide for a private right of action.

But it is arguable that private causes of action for data breaches remain an important mechanism for individuals to recover for loss of their personal information, including by aggregating individual claims, which are sometimes limited in monetary value, into impactful class actions. They serve an important function not only of ex post remediation but also as an ex ante device to incentivize companies to improve their security practices.

That said, it is worth noting that were an individual to suffer actual damages as a result of a breach in which notification was delayed, those damages would conceivably constitute the “harm” necessary to provide standing in a case claiming the company was negligent or failed to reasonably secure confidential and personal consumer information. This would ostensibly constitute an actionable cause even if not under the breach notification statute.

Conclusion

The proposed bill generally meets, and in some cases exceeds, the standards set by existing breach notification laws. There are three notable exceptions: the absence of a private cause of action for individuals harmed by a failure to notify; the proposed bill’s definition of a covered entity, which effectively exempts smaller businesses and individuals that might have been subject to notification requirements under the majority of current laws, and the omission of different data formats and data sets from the definition of SPII. As this analysis suggests, other differences between the existing system and the proposed national standard appear to diminish neither the efficacy nor the strength of the proposed standard relative to the existing laws. While it is true that the language of the bill may change as it passes through Congress, analysis of the bill in its current form demonstrates that the proposed national standard comprehensively extends the fundamental requirements of existing laws on a national scale.