What's wrong with the ICO's draft guidance on controller-processor contracts?

Contributors:

W. Kuan Hon

Of Counsel

Dentons

Those struggling with controller-processor contracts in the run up to May 25, 2018, will be familiar with Articles 28 and 82 of the EU General Protection Regulation — what some might call another kind of PETs, the "palindromic evil twins" of GDPR.

The GDPR fundamentally changes the balance of obligations and liabilities between controllers and processors. As data protection practitioners know, Article 28 sets out mandatory minimum terms that must be included in contracts between controllers and their processors, and requirements regarding processors' use of subprocessors (termed "another processor"). Article 82 entitles "any person" to compensation from the controller or processor for damage suffered by the person as a result of a GDPR infringement, with exculpatory provisions on, effectively, proving non-responsibility. And of course, for the first time, processors will have direct statutory obligations for certain data protection matters.

All this means that contracts are of huge practical importance, particularly as the GDPR won't "grandfather in" pre-existing contracts: Strictly, all controller-processor contracts, even pre-existing ones, must be brought into compliance by May 25, 2018. Yet, inexplicably, controller-processor contracts and liabilities don't seem destined for any guidance from the Article 29 Working Party, at least according to the WP29's published work programs/roadmaps to date. However, some national regulators have picked up the baton. On September 13, the U.K. Information Commissioner's Office issued draft guidance, Contracts and liabilities between controllers and processors, for a brief consultation closing Oct. 10.

The ICO has produced some excellent guidance in the past. But here, the ICO's draft guidance seems redolent of a twentieth-century controller world, giving not even one online example. The ICO's guidance addresses controllers almost entirely throughout, with only a short section for processors. The draft guidance also contains some errors and omissions. Most disappointingly, it copies the GDPR's text on the difficult uncertainties that practitioners face in real life, without providing real guidance — particularly in relation to commoditized IaaS and PaaS cloud computing services (see my previous IAPP article on GDPR and cloud). This approach will not be of assistance to SME readers either — presumably the target audience for the guidance.

Here are some of the main issues.

In general

The draft ICO guidance does not cover:

- Whether the requirement to enter into an Article 28-compliant contract applies to processors too; i.e., could a processor be fined 2 percent or €10m under Article 83(4) if it doesn't have compliant contracts with all its controllers in place by May 25, 2018?

- The GDPR qualification that, for two mandatory contractual terms obliging processors to give controllers certain assistance, the nature of the processing must be taken into account (Articles 28(3)(e)-(f)); that processors must take measures to help controllers meet data subjects' requests regarding their rights only "insofar as this is possible" (Article 28(3)(e)); and that the "nature of the processing and information available to the processor" must be taken into account in the context of processors helping controllers to comply with controllers' obligations regarding security, personal data breach notification, DPIAs and prior consultation with supervisory authorities (Article 28(3)(f)).

- These qualifications are particularly relevant to commoditized cloud services, which are self-service (i.e., customers can access and edit data directly themselves over the internet, without needing the cloud provider to do anything specifically) and "hyperscale," with thousands or even millions of customers.

- That nothing in the GDPR prohibits processors from charging reasonable fees for their extra work in providing any required assistance or information (or for undergoing customer audits). If processors are not allowed to charge for the extra assistance, etc., they are likely to raise their prices, perhaps even generally for all customers, so being permitted to levy fees for any extra "assistance" work seems the fairest approach.

Processors and subprocessors – role and use

Under the heading, "Who is liable if a subprocessor is used?" (p.24), the draft ICO guidance states: "The subprocessor has the same direct responsibilities and liabilities under the GDPR as the original processor has." That cannot mean that a subprocessor is directly responsible as a processor under the GDPR. If so, that would require a controller to enter into a direct Article 28-compliant contract with every one of it's processor's subprocessors, and each subprocessor would be directly exposed to fines for infringement, etc., which can't be right (and would render superfluous Article 28(4)'s required "flowdown" to subprocessors of the mandatory controller-processor contractual terms). This sentence needs clarification.

The draft guidance does not:

- Clarify that when processors inform controllers of intended changes in subprocessors under Article 28(1), "thereby giving the controller the opportunity to object to such changes," giving the controller a contractual right to terminate if it objects to a change should be sufficient, particularly with cloud services;

- State whether a subcontractor should be considered a subprocessor of personal data, i.e. "another processor," under Article 28. I've argued it should not be, unless it actually has access to intelligible personal data and intends to access personal data, and more than just incidental access for maintenance purposes (see my recent book and web update regarding the Bavarian DPA's approach);

- Clarify when obligations must be flowed down to subprocessors. Article 28(4) requires flowdown when a processor "engages another processor for carrying out specific processing activities on behalf of the controller." What are "specific processing activities" in this context — bespoke processing tailored for the controller along the lines of traditional outsourcing, so that the flowdown obligation doesn't apply to commoditized cloud?

- Clarify what obligations must be flowed down — must all subprocessors assume direct obligations to the controller as third-party beneficiary, or is it enough that they assume contractual obligations to their immediate higher-level processor?

- Clarify how far down the chain the flow must go (assuming the following qualify as "another processor"): third-party data center operator, network/communications provider, payment services subprovider;

- Clarify if all the Article 28 contractual obligations have to be imposed on subprocessors who are individuals, e.g., for support services.

Liability and compensation

The draft guidance does not clarify:

- Article 82(1) and Recital 146's statement that "any person" who has suffered material or non-material damage can sue for compensation. Does this entitle a processor to sue the controller or subprocessor if it has suffered damage (e.g. compensation claim, reputational damage) due to an infringement by the controller or another processor, or vice versa?

- Whether data subjects can choose to sue anyone in the supply chain that they wish, including "another processor," i.e., even a subprocessor far down the chain (Article 82, particularly Article 82(4), and Article 28's reference to "another processor," suggests this, and many take the view this is the case)

- That only controllers and processors (not their employees, etc.) are exposed to administrative fines under Article 83(4), despite Article 29, which says broadly that the "processor and any person acting under the authority of the controller or of the processor, who has access to personal data, shall not process those data except on instructions from the controller, unless required to do so by Union or Member State law." And why is Article 29 is almost identical to Article 32(4) on security?

Miscellaneous

The ICO draft guidance:

- Says nothing about joint controllers (covered under Article 26), or about "controllers in common," which is a concept under current U.K. law — will this concept continue, how should controllers in common comply with Article 26; e.g., as joint controllers, can one controller in common be sued for compensation under Article 82 for another controller in common's actions?

- Address the ambiguous "Processing by a processor shall be governed by a contract or other legal act under Union or Member State law …" to clarify that (as the travaux preparatoires show) "Union or Member State law" applies only to the "legal act" — the contract itself may be under any applicable law.

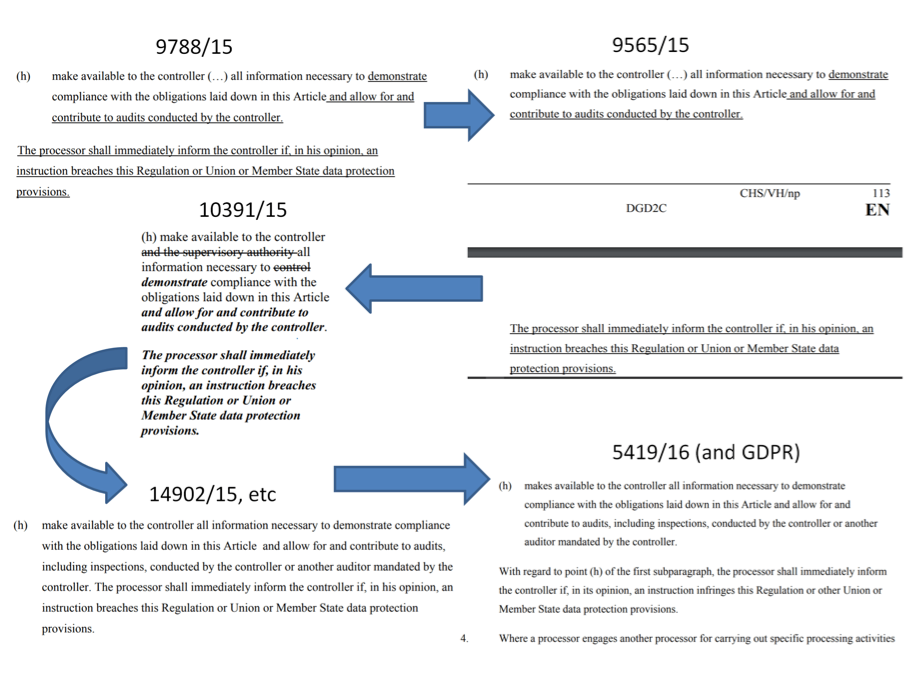

The good news — at least the ICO's draft guidance (p.16) seems to have come down on the side of processors' "inform the controller" obligation having to be a contractual term as part of point (h), rather than a separate direct statutory obligation. It is difficult to interpret the second subparagraph of Article 28(3) — "With regard to point (h) of the first subparagraph, the processor shall immediately inform the controller if, in its opinion, an instruction infringes this Regulation or other Union or Member State data protection provisions" — probably due to a formatting confusion during the GDPR's legislative passage (see diagram below). Attention to indentation matters!

But this subparagraph still makes little sense in the context of (h), which is about the processor providing information, not the controller's instructions to the processor (unless the instruction is to provide information?). Also, surely it should not require processors to incur the costs of taking legal advice on data protection laws in the EU and all member states where the controller and/or processor operates whenever the controller gives the processor any "instructions," i.e., effectively require processors to provide legal advice to their controllers!

In summary, the draft does not provide much guidance on most of the practical difficulties with Articles 28 and 82, and I hope the final guidance will at least deal with some of the issue raised above.

photo credit: Project 365 Day 130: Flag via photopin(license)