A procrastinator’s guide to data controller registration in Turkish data protection law

Contributors:

Onur Sumer

CIPP/E, CIPM

Group Legal Counsel Privacy

Ericsson

Editor's Note: After publication of this article, the Turkish DPA postponed the deadline for registration on the Register of Data Controllers from Sept. 30 until Dec. 31.

The first two milestones of the Turkish Data Protection Law were marked when the law first came into force April 7, 2016, and when the grace period ended April 7, 2018. The third milestone is only months away, taking place September 30, 2019, the deadline for data controllers to register their data mapping with the Turkish Data Protection Authority.

The TDPL is Turkey’s first comprehensive data protection legislation which was drafted mostly in line with the EU’s Directive 95/46/EC. The TDPL requires data controllers to notify the Turkish DPA of their processing activities, similar to the requirement under Article 18 of Directive 95/46/EC, which was later abolished by the EU General Data Protection Regulation.

However, Turkey’s approach to the obligation to notify the supervisory authority of the processing of personal data is more comprehensive and complicated than it was in the EU. For data controllers that have not made a preliminary analysis, it is difficult, if not impossible, to compile the data mapping the Turkish DPA requires to be notified.

In terms of data mapping and notification, the Turkish DPA sets forth two main requirements for data controllers: (i) registering with the Turkish DPA and (ii) preparing a personal data processing inventory. In comparison with the EU data protection practice, the first is an extended approach to the notification requirement that existed in Directive 95/46/EC and the latter is similar to the GDPR’s record keeping requirement under Article 30.

Register of data controllers — Notification

The TDPL requires that data controllers notify the Turkish DPA of:

- The name and address of the controller and its representative, if any.

- The purpose or purposes of the processing.

- Information regarding the categories of the data subject and of the data.

- The recipients or categories of recipients to whom the data might be transferred.

- Personal data to be transferred to other countries.

- Measures taken in relation to the security of the personal data.

- The maximum period required for the purpose of processing of the personal data.

The contents of the notification bear noticeable similarities with Article 19 of Directive 95/46/EC. On the other hand, items regarding processing periods and security measures indicate influence from the GDPR’s Article 30, as these two items were not initially covered in the EU Directive’s notification requirement. Further influence from the GDPR’s record keeping requirement is apparent in the Turkish DPA’s secondary regulations.

However, the major difference is that while the GDPR does not require these items to be registered with supervisory authorities and simply requires the data controllers to maintain records of their processing activities, the TDPL requires that such records be notified to and registered with the Turkish DPA.

VERBIS

The Turkish DPA’s Register of Data Controllers Information System is called VERBIS and operates with quite a complex workflow. Data controllers that are subject to the registration requirement first need to fill out an application form and then send a copy of the signed form to the Turkish DPA. After reviewing the application, the Turkish DPA will provide login information to the data controllers. The data controllers will then log onto VERBIS and assign a Turkish citizen natural person as their contact person. The contact person can then log onto VERBIS through Turkey’s e-government portal and start filling the data controller registration form.

At this time, VERBIS does not support APIs or spreadsheets. Instead, the contact person is prompted to complete registration through multiple choice forms with predetermined categories of personal data, processing purposes, data subjects, data recipients, and security measures. It is important to note that VERBIS is not a data-mapping model built on processing activities; instead, it builds up starting from personal data categories, i.e., the contact person selects the predetermined category of personal data first and then selects the predetermined purposes of processing that apply to that category of personal data and so on.

Providing the necessary information to the Turkish DPA would require the data controller to map and analyze its data processing activities in light of the TDPL. This also applies to data controllers, which are already subject to the GDPR. Although the information required in VERBIS is similar to the records to be maintained under Article 30 of the GDPR, such records may not be directly applicable because VERBIS is based on categories of personal data rather than the purposes of processing and predetermined items need to be selected throughout the process, while free-text input is very limited.

Personal data processing inventory — Record keeping

The Turkish DPA’s “Regulation on Register of Data Controllers” requires all data controllers, that are not exempt from the registration requirement, to prepare a personal data processing inventory. The scope of what needs to be included in a personal data processing inventory is, in principle, similar to the contents of the VERBIS registration.

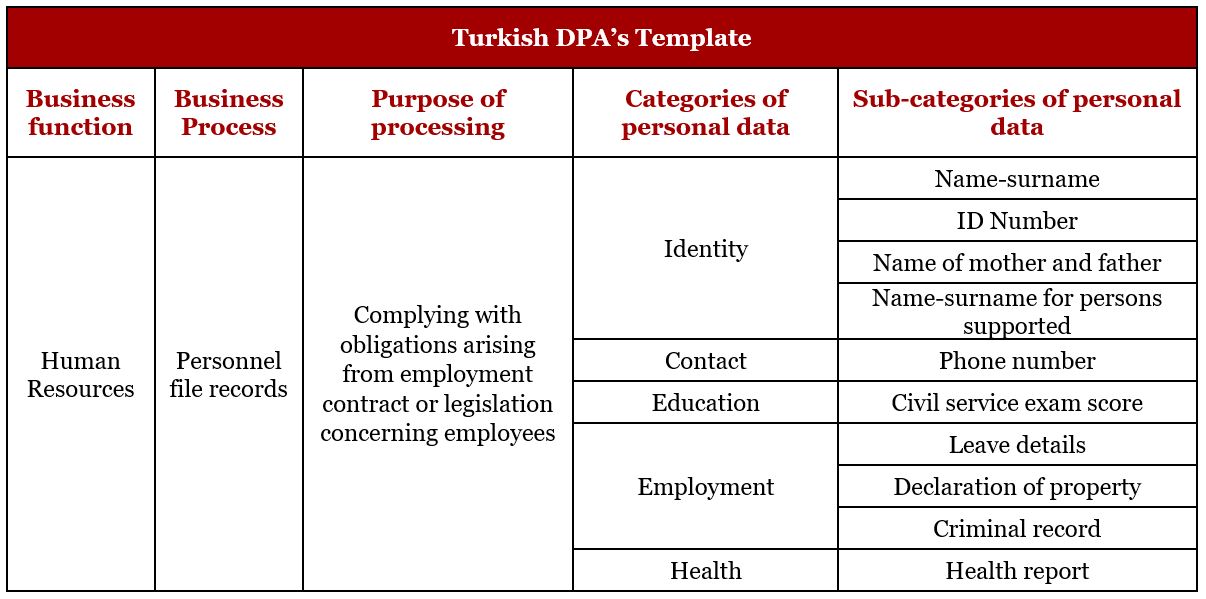

The Turkish DPA recently published its guidelines regarding personal data processing inventory. According to the guidelines, records of processing activities that are notified to the Turkish DPA should reflect a general view, as they only include categories of personal data. On the other hand, the personal data processing inventory should take a more detailed approach to the processing activities. The level of detail even exceeds the expectations of EU DPAs under the GDPR’s Article 30.

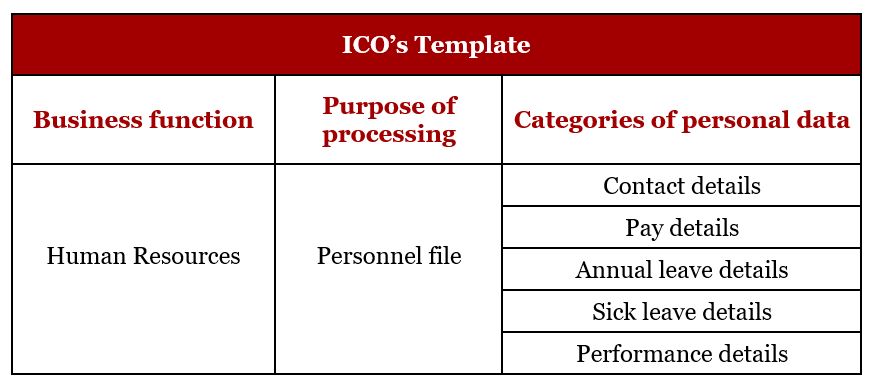

In fact, the template spreadsheet attached to Turkish DPA’s guidelines demonstrates not only categories of personal data, but also their sub-categories. Below is a comparison of the Turkish DPA’s personal data processing inventory template against the GDPR Article 30 documentation template, published by the U.K.’s Information Commissioner’s Office:

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

The Good: Exemptions

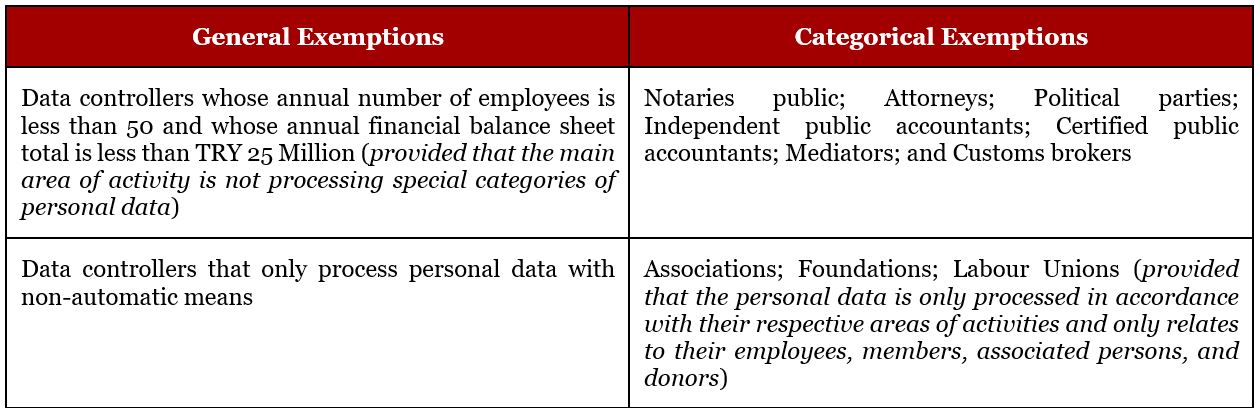

The Turkish DPA has so far granted exemptions from the registration requirement for certain types of processing activities, as well as for data controllers concerned in certain fields of work or who have a relatively small business:

The Bad: Deadlines and Fines

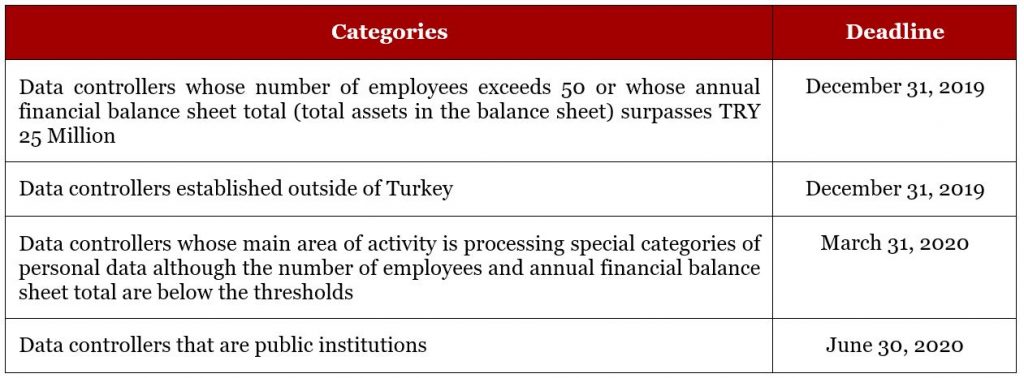

The Turkish DPA announced four deadline categories for registration to VERBIS in its decision No. 2018/88 and dated July 19, 2018:

Data controllers that are obliged to register to VERBIS yet fail to do so by the deadlines above may be subject to administrative fines. Under Article 18 of the TDPL, breaching the notification and registration requirement may result in an administrative fine from TRY 29,411 to 1,470,583 (up to USD 242,000).

The Ugly: Territorial Scope of the TDPL

When navigating foreign data protection legislation, the first thing any foreign data controller should consider is the territorial scope and the extra-territorial applicability. However, this is not an area where the TDPL provides clear guidance. In contrast to the GDPR and most comprehensive data protection laws, the TDPL does not have a provision on territorial scope, i.e., the TDPL does not state when a foreign data controller would fall within the scope of the TDPL.

Nevertheless, the Turkish DPA wiped out any practical arguments when it set forth in its secondary regulation the requirement to designate a representative in Turkey and the procedure for registering to VERBIS for data controllers established abroad. Although it is not clear when a particular processing activity would fall within the scope of the TDPL, certain administrative actions taken by the Turkish DPA construct a perspective on the extraterritorial application resembling that of the GDPR.

The Turkish DPA published the number of breach notifications filed by foreign data controllers on its website and even issued a TRY 1.65 million fine to Facebook over an unnotified breach. Neither the published breach notifications nor the Turkish DPA’s decision regarding Facebook include justifications or arguments on the Turkish DPA’s jurisdiction. However, almost all of these cases included an emphasis on “persons affected in Turkey.”

It could be argued that reading between the lines, these announcements signal that the Turkish DPA may be approaching such cases with a perspective similar to the territorial scope of the GDPR. Although there is still much confusion in terms of the territorial scope, it should be noted that the Turkish DPA’s recent fine imposed on Facebook demonstrates that the Turkish DPA is willing to take action against foreign data controllers, at least when persons in Turkey are affected.

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Submit for CPEs