The Modern Sword of Damocles: Risks and Rewards of AR glasses

Contributors:

Brandon LaLonde

CIPM

Research & Insights Analyst

IAPP

The ancient Greek parable of the sword of Damocles features Dionysius II, the despotic king whose wealth and power are overshadowed by his fear of capital retribution from his citizenry. One day, a courtier named Damocles began to heap praise upon the ruler: "How happy you must be! You have here everything that any man could wish." In response, Dionysius offered him the throne for a day, and Damocles could barely contain his excitement. After indulging in kingly luxuries for a time, Damocles looked up to see a razor-sharp sword dangling perfectly above his head, held up only by a single horsehair. He quickly returned the throne, realizing that the enviable life of a king was shadowed by a constant, looming threat.

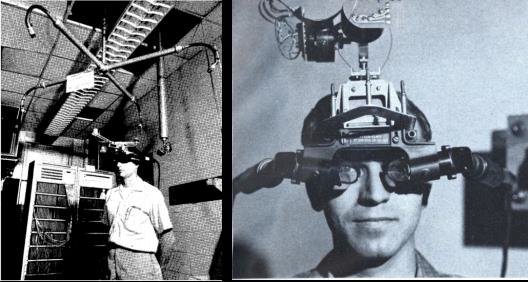

This story must have been in the heads of Professor Ivan Sutherland and his team at the University of Utah when, in 1968, they created what is widely considered the first augmented reality system. The head-mounted display was so large and unruly that it had to be hung from the ceiling, earning the nickname "the sword of Damocles." The device presented basic wireframe graphics through semitransparent lenses, allowing users to see their physical surroundings while simultaneously viewing digital overlays. Crucially, it included components that enabled head tracking technology. Today, head tracking and physical transparency are pillars of AR technology and differentiated from other similar technologies like virtual reality — though there is oftentimes some overlap.

Evidently, Sutherland's original device shares very little in common with what today's consumers expect from AR smartglasses. Current technology, like the XREAL One Pro or Meta's Orion prototypes, provide sleek wearable products that act as extensions of our human cognition. Beyond head tracking and transparent lenses, many modern glasses now include features like voice recognition, eye tracking, built-in speakers, microphones and high-definition cameras.

Naturally, the increase in portability and technological features, as well as their overall increased ease of access, have created novel use cases for such wearables. They also present contemporary privacy and artificial intelligence concerns for users of the technology and, perhaps more pressing, bystanders who are exposed to the technology by proxy.

What's with all these letters?

In general, there are four types of "realities" used to categorize these technologies:

Virtual reality provides an immersive digital environment by using a headset with built-in screens and head tracking. Virtual reality headsets, like the Meta Quest and HTC Vive, also commonly include some form of controller that allows you to interact with the digital world. While VR headsets map out your surroundings for spatial awareness — you don't want to accidentally trip over your couch while using the headset — they do not provide a way for you to see and/or interact with your actual physical environment.

Augmented reality is similar to VR, except it allows a view of the real world with digital elements incorporated into your environment. For example, some AR glasses can translate written words on the fly, overlaying the translated text onto whatever you're looking at.

Mixed reality is also similar to AR, except instead of simply overlaying digital information onto the physical world, both physical and digital elements are able to interact. One hypothetical instance of MR is a virtual companion who can process information about your physical surroundings and react accordingly to them.

Extended reality is a catch-all term for the above three types of technology.

When specifically discussing glasses, the term smartglasses is commonly used as a catch-all term. Not all modern smartglasses have AR capabilities; the popular Ray-Ban Meta Gen 2 smartglasses are a good example of this.

What's the buzz about?

In daily life, AR glasses present compelling use cases. Features like open-ear audio allow users to listen to music and make phone calls without having to put in headphones or even touch their phone. Similarly, built-in cameras let users take photos and videos at a moment's notice, demonstrated recently at Super Bowl LX when a fan stormed the field and recorded the entire experience with his Ray-Ban Meta glasses. The built-in voice commands, a common feature of many AR glasses, further reduce the friction involved in performing routine tasks that many people carry out daily. In addition to translating written text, some AR glasses provide live translation of a conversation, offering both an audio translation in the ear and a written transcription displayed on the glasses in real-time.

AI technology has also become central to these product offerings. Developers tout this integration as a way to further enhance their product, transforming AR glasses into personal assistants capable of everyday tasks. While not AR glasses by definition, my experience testing the Meta Gen 2s included use of its Meta AI experience.

Saying "Hey Meta…" would activate the glasses, and I was able to ask it questions such as, "What am I looking at?" or "Where did I park?" I specifically chose these questions as they're both advertised as example questions on Meta's product website, and, for the most part, Meta AI responded accurately. While these experiences highlight the utility that is driving year-over-year sales, they also bring privacy and AI concerns to the forefront.

As a health and accessibility aid

Besides casual use, emerging research and development explore how AR glasses can aid users with health conditions or accessibility requirements. One study provided patients with chronic heart or lung diseases access to AR glasses that guided them through customized exercises via a virtual physiotherapist agent as part of a telerehabilitation program. The patients ultimately found "value in [the] program."

Another study looked at the potential benefits of Apple's AR headset for people who experience visual deficits, noting that the technology could enhance daily life for people diagnosed with nyctalopia, or night blindness, macular holes and strabismus by changing how users view their environment and providing personalized health recommendations and at-home treatments based on their condition.

Innovation is also targeting cognitive health through scientists and hobbyists. The VisionXcelerate glasses were developed to assist people with dementia by "[providing] real-time assistance, [helping users] overcome some of the challenges posed by memory loss and [helping] wearers identify objects and faces." The glasses also provided a way for caregivers to remotely monitor and assist their care dependents through built-in health sensors and cameras. A similar product projects a blue target that users could direct at objects, identifying what they are looking at and how to use it.

AR glasses and related technology are not only nifty gadgets for casual users, but they also present real innovation for those experiencing any number of health issues. A third use case has also emerged: AR glasses as a professional tool.

As a professional tool

The professional utility of AR glasses has seen a massive surge, particularly in high-stakes environments like health care and manufacturing. For health care professionals in training, AR glasses can overlay human anatomy onto mannequins, offering more effective methods for learning procedures such as ultrasounds and emergency medical interventions. In surgical theaters, AR overlays allow doctors to not only visualize a patient's internal anatomy but also access important medical information about their patient, like heart rate and blood pressure.

Similarly, in industrial settings, AR technologies streamline training for complex assembly tasks and work in hazardous environments. One recent study indicated that, in general, workers using AR for visual inspection demonstrate higher "attentive work duration" and more consistent adherence to safety standards compared to those using mobile devices or paper manuals.

Specifically, Microsoft's HoloLens is an AR device line primarily marketed as a business tool. Large manufacturers like Honeywell have adopted the technology as part of their onboarding, where trainees are shown "various workplace situations, such as a cable or power supply failures." Honeywell claims use of the HoloLens has "demonstrated up to a 100% improvement in outcomes versus traditional training methods, and reduces the time it takes to train a new employee by up to 66%."

AR glasses have also been shown to support and improve outcomes for professionals in education, architecture and warehouse operations.

Privacy concerns

The always-on nature of these devices, paired with some of their invasive features, like cameras and microphones, has sparked debate over privacy and bystander consent. In fact, in the immediate aftermath of the release of Google Glass in 2012 — the product that kickstarted the modern wave of AR glasses — privacy concerns were top of mind for many people. It raised many of the same big questions we're still asking today.

As a bystander, how do you maintain a sense of privacy when you could seemingly be inconspicuously recorded at any time? Holding up a smartphone is a lot more obvious than recording with a pair of glasses. Indeed, manufacturers have attempted to mitigate this concern by making it obvious when glasses are in recording mode, but crafty hackers have quickly found ways to thwart these attempts. Taken a step further, this raises the possibility of potentially malicious actors connecting their glasses to a facial recognition system to identify anyone in sight, something that has already been demonstrated as a proof of concept. Meta has even recently floated the idea of adding native facial recognition capability to their smartglasses product line. The cameras could also inadvertently or intentionally capture sensitive information, such as passwords or private documents, in certain settings.

There are also privacy concerns for the user. Scientific reviews have raised concerns about "granular data collection," where sensors capture involuntary body signals like heart rate, eye movements and emotional responses. As I've written in the past, small amounts of anonymized personal biometric data can be used to accurately predict a myriad of health and related conditions. Researchers have cautioned that users are often unaware of how invasive the sensors on AR and related technologies can be compared to traditional mobile devices.

Furthermore, workplace surveillance is a growing concern. Amazon faced backlash for tracking their warehouse workers during their shift, monitoring their "time off-task" using radio-frequency handheld scanners. With the proliferation of AR glasses in warehouse management, it's not hard to imagine a scenario where workers are required to wear them as part of their normal duties, all aforementioned privacy concerns in tow.

AI concerns

The integration of AI adds a layer of complexity, particularly regarding data transmission. Most AR and smartglasses rely on cloud-based AI to process tasks like object recognition and audio interpretation, meaning a constant stream of audio-visual data is commonly sent to external servers, making this data particularly sensitive and valuable. Besides this, risks inherent in every AI model are also now at the forefront of AR technology.

Consider model bias: Depending on use case, AI could misidentify people or filter reality in a way that reinforces stereotypes. There is also a risk of an altered reality where your physical world is shaped by your AR glasses based on past behavior using AI to analyze your audio, visual and location-based information. While the idea of ad-targeted products during a shopping trip may sound dramatic, the "dawn of immersive personalization" has already been examined.

What to do?

Looking ahead, trust in AR glasses by both consumers and digital professionals will rely heavily on the public's perception of privacy-preserving and non-invasive tactics, as emphasized by the loud objection to Google Glass years ago. We are currently in a period where technology is seen as outpacing regulation, particularly regarding biometric data and informed consent. While the benefits in health care, industrial safety and personal productivity are well supported, the risk of covert surveillance and privacy infringement remains a significant barrier to mainstream trust.

This is not to say that these devices are shielded from regulatory efforts. For professionals who may be encouraged or forced to wear them as part of their jobs, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has warned that, under the Americans with Disabilities Act, "medical examinations and disability-related inquiries are permitted only if related to the specific job of the employee, and the exam/inquiry is consistent with a business necessity."

Any health care workers in the U.S. using this technology will almost certainly be subject to the Health Insurance and Portability Accountability Act, specifically its security rule. Additionally, the use of this technology in the workplace may trigger, at the very least, a risk assessment obligation under the California Consumer Privacy Act; Connecticut, Delaware and New York all require employers to notify their employees of any on-the-job monitoring.

Outside of a professional context, a European Commission spokesperson recently reiterated, "Any recording of individuals must be clearly communicated and must have a legal basis to record individuals," referencing both the EU AI Act and the EU General Data Protection Regulation. Additionally, in December 2025, the Court of Justice of the European Union concluded that data gathered through direct observation via technologies like smartglasses is considered collected from the data subject and is therefore subject to the transparency requirements set out in Article 13 of the GDPR. Users in the U.S. may also have to contend with the grey area of wiretapping, as some states require two-party consent for recording "calls."

Regulation hasn't necessarily caught up with the rapid advances of AR technology. Is recording a conversation with AR glasses legally recognized as a call under federal and state wiretapping laws? This is ambiguous. However, both users and deployers should be mindful that regardless of it being a rapidly budding technology, it is by no means an unregulated technology.

For these devices to become as trustworthy and successful as, say, the smartphone, manufacturers and regulators must prioritize privacy by design. One common approach developers use to address this is on-device processing, where sensitive processing — such as conversation detection or facial recognition — happens locally on the device's silicon. This method, supported by techniques like differential privacy, aims to reduce the risk landscape by locally processing data on the device and subsequently deleting it — never sending information to an external server for processing or model training. This method is an increasingly popular feature when discussing user privacy and safety. Apple, for example, uses it with their AR headset Vision Pro when analyzing AI requests. Manufacturers who don't currently utilize similar techniques attempt to give users control over their data; for example, Meta's glasses emphasize this by reminding users that they can delete their voice recordings and opt-in to Meta AI only if they choose.

This technology will also ultimately require a shift in cultural norms. Users should be fully transparent with their audience if they're using said AR technology and disable the "smart" features of glasses when they are not needed. Bystanders should remain vigilant for physical cues, like recording LEDs, and exercise their right to privacy by asking users to power off or remove the technology when in private or sensitive settings.

As digital governance professionals, the challenges are widespread. Regulators, while acknowledging that many laws and regulations cover AR technology, have to contend with the fact that there are major gaps for this technology and precedent may need to be set in the near future for clarification's sake. Digital governance professionals keen to deploy this technology in their organization need to be aware of the legal and ethical concerns that come with its use.

Governance professionals of all stripes need to be aware that this technology has a wide risk landscape, something that will increasingly need to be accounted for in their digital risk management approach. The sword of AR glasses, and smartglasses in general, is already proverbially dangling above our heads. Whether it's characterized as a tool of empowerment or a threat to privacy and AI governance depends on how users and governance professionals choose to respond.

Brandon LaLonde, CIPM, is the research and insights analyst for the IAPP.

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Submit for CPEsContributors:

Brandon LaLonde

CIPM

Research & Insights Analyst

IAPP