In September, the U.K.’s Department for Digital, Media, Culture and Sport released a consultation document about the future of data protection law in the U.K.

The consultation proposes a raft of changes to the U.K.’s data protection law. Some are small changes and clarifications intended to resolve uncertainties in the EU General Data Protection Regulation’s drafting, while others are fundamental reforms to the operation of the U.K.’s data protection laws and the obligations and protections they bring. All organizations operating in the U.K. should be interested in potential changes to:

- Data subject rights (to make them less burdensome).

- Accountability (potentially burdensome).

- Data transfers (significantly more flexibility).

- E-privacy (possibly helpful, although proposals not clearly articulated).

There are also proposals of significant interest to those involved in research and AI, and reforms on the powers and governance of the Information Commissioner’s Office, the supervisory authority.

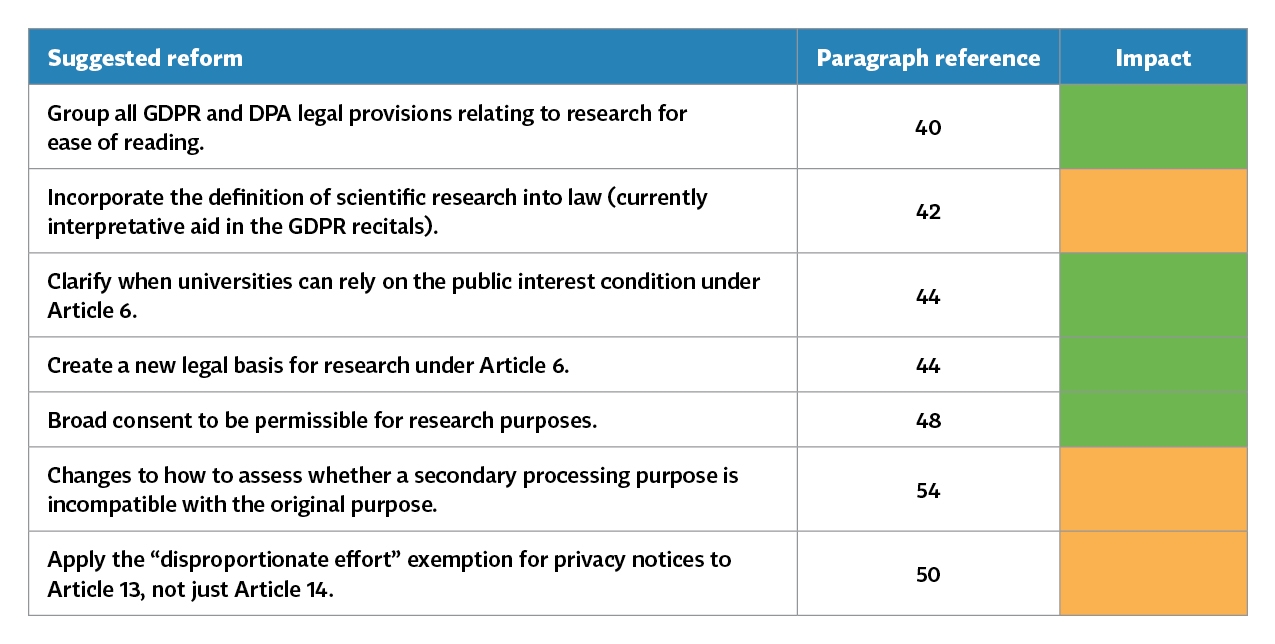

The consultation is open to all respondents until Nov 19. The DCMS document sets out structured questions on each of the proposed changes and encourages respondents to provide their own views and experiences on the challenges and possible solutions the U.K.’s current regime presents. Below, we summarize the main changes proposed in the consultation document, with a color coding showing the degree of change to the U.K.’s existing data protection compliance framework. Green means a proposal makes no significant change to existing legal framework, amber a medium change and red a significant change.

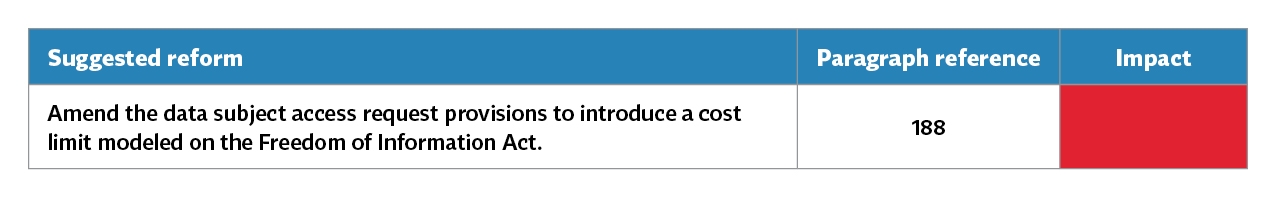

Data subject rights

This proposal will be welcomed by controllers in the U.K. Many organizations have felt the burden of “weaponized DSARs” and the introduction of a cost limit would reduce this burden. The suggestion made by DCMS is that this should be based on the existing and well-established regime under the Freedom of Information Act, which allows public authorities to refuse freedom of information requests that cost more than 450 - 600 pounds (depending on the type of organization). Interested parties wishing to respond to the consultation should consider submitting information about what the cost limit should be, or criteria used to establish it. A sliding scale depending on turnover and sector may be a good model.

Accountability

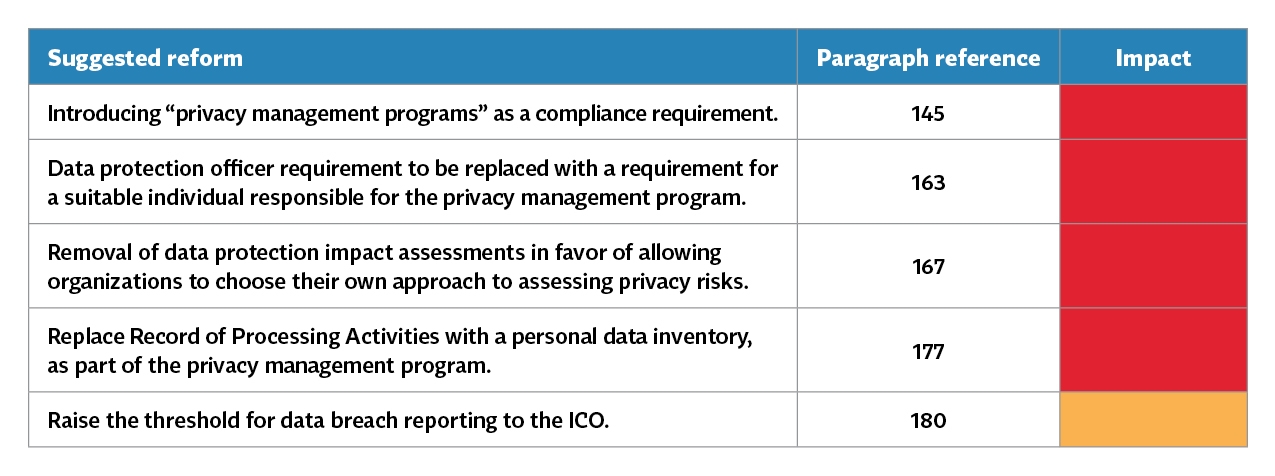

The departure from the existing GDPR framework for accountability is puzzling. DCMS’s stated reason for the proposed reform is that current accountability obligations place a “disproportionate administrative burden” on organizations, yet its proposals involve replacing existing accountability requirements with other very similar (and no less burdensome) obligations. With the exception of the higher threshold for breach reporting, all other accountability requirements have been replaced with a different compliance requirement, often with the choice of the format left to organizations. This would likely create more work for organizations, which would need to assess whether their existing GDPR documentation matched the new U.K. requirements. For example, there is a suggestion that GDPR data protection officers could not serve as the person responsible for the privacy management program (as the independence they require for GDPR purposes would — implicitly — disqualify them from this new role), so that an organization that chose to retain its DPO would need to appoint an additional data protection professional (164). The proposals seem to diverge from the GDPR without providing any discernible benefit to organizations in the U.K.

Data transfers

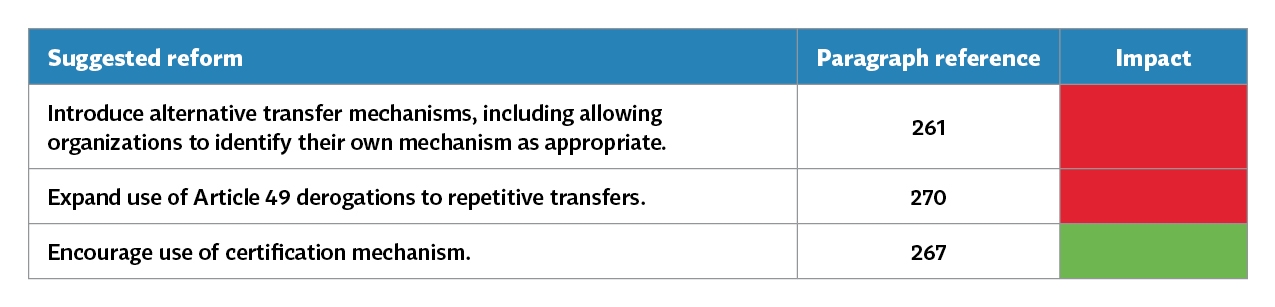

In the wake of “Schrems II” and the associated EDPB guidance, transferring data out of the EU and U.K. has been complicated. The consultation proposes a number of reforms to improve the U.K. aspect of this, from encouraging adoption of existing mechanisms (use of codes of conduct) to widening existing mechanisms (such as the derogations under Article 49 GDPR). It also includes a more controversial proposal to allow exporters to make their own decisions about how to protect personal data being transferred out of the U.K., including by using contracts developed by the contracting parties without the ICO’s review or approval. This proposal is based on the approach taken in New Zealand and was possible in the U.K. under the Data Protection Act 1998.

There are also proposals to change the process for the U.K.’s adequacy assessment of third countries (see paragraphs 247-254), which are not assessed in this article as they do not directly affect compliance requirements.

Changes to ePrivacy

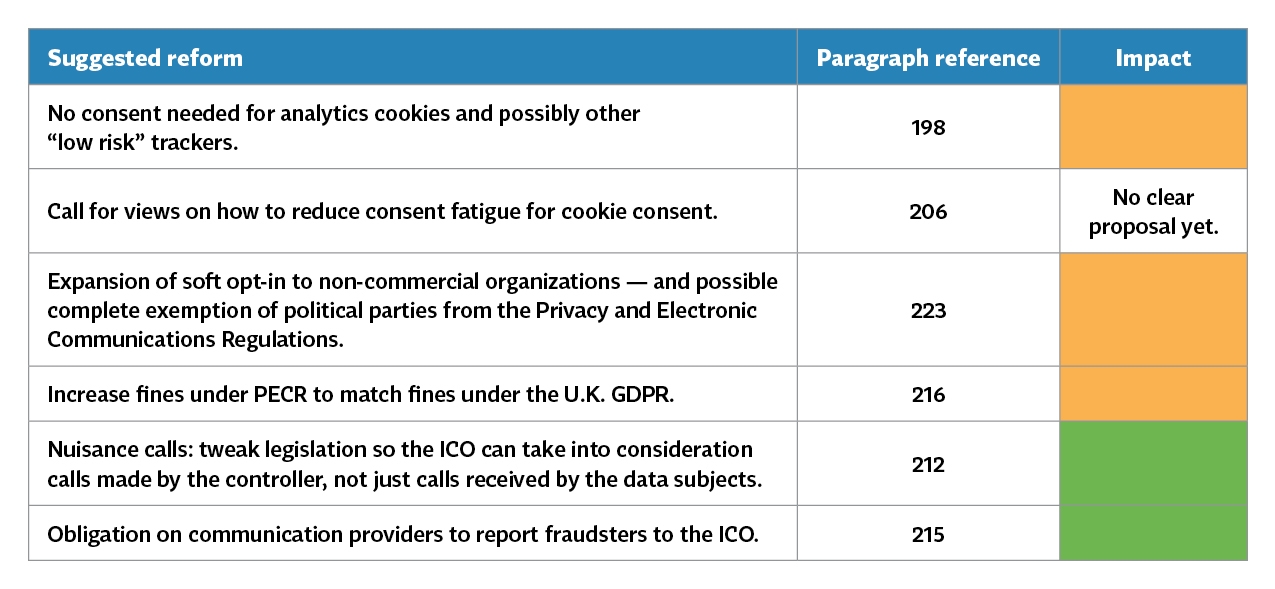

The consultation has widely been announced as a reform of the U.K. GDPR, yet a section on the U.K.’s Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations has also been included. Most changes in this area are relatively minor and are likely to be welcomed both by controllers and data subjects. There is an attempt to obtain cross-party support for at least some of the proposals by proposing to exempt political parties from these rules in their entirety, although the consultation document does acknowledge that the prospect of receiving automated calls from political parties may not be welcomed by everyone.

The proposal also includes a call for views on how organizations could comply with the GDPR’s principles of lawfulness, fairness and transparency “without use of the cookie pop-up notices.” This section references browser settings as a possible option but offers no other suggestions, so it is hard to assess the possible impact of this.

Research and reuse of data

In line with the U.K. government’s National Data Strategy, the consultation document pushes for reforms to encourage research in the U.K. The document stresses that data protection laws are complex and difficult to navigate, which discourages researchers from using personal data.

The proposal to consolidate all research-specific data protection provisions may achieve the aim of bringing greater clarity to the area, though it is unlikely to have a strong impact. The proposal also suggests moving a number of research-related recitals into the Articles of the U.K. GDPR to increase legal certainty. As part of this, the U.K. GDPR would define scientific research in law, and the consultation seeks views as to what this should be defined as.

There is also a proposal to include a new legal basis for scientific research under Article 6 U.K. GDPR, to match the condition for processing sensitive personal data for research purposes under Article 9. Currently, researchers would be likely to rely on either research being necessary for a task in the public interest or necessary for a legitimate interest, so it is unclear what benefit this would bring; further, to the extent clarity could help, it could be achieved by guidance instead of primary legislation.

Much of the discussion on research focuses on challenges faced by universities. The private sector is also a critical part of the U.K. research base and it would be advisable for private sector organizations engaging in research to make clear to DCMS that their interests must also be considered.

The consultation includes a number of proposals on how to change the law relating to reuse of data for research purposes. The proposals in this area are not wholly clear and are in some cases contradictory. They include clarifying that a broad consent is permitted when obtaining consent for research and that reuse for research is always compatible with the original purpose, both of which would be welcome but could be achieved by regulatory guidance rather than new legislation. There are also (unclear) proposals to allow further processing for incompatible purposes when this safeguards an important public interest (54). The Data Protection Act 2018 already allows this for the public interest purposes specified in Schedule 2. Allowing a general public interest override to purpose limitation will significantly weaken protections for individuals, so it would be useful to understand the size of the problem that DCMS thinks it is addressing with this proposal.

It is also striking that the consultation does not make any reference to the laws relating to patient confidentiality beyond data protection law. In the authors’ experience, it is the law in this area which is the biggest constraint on research — both as a matter of principle and because of uncertainty in interpretation. No amount of tidying up data protection law will achieve significant benefit unless this is addressed.

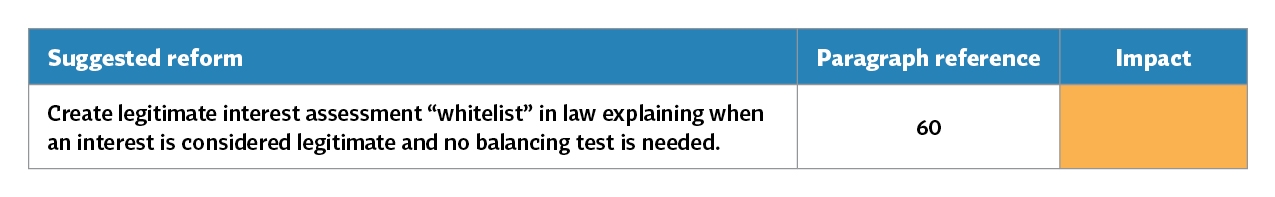

Legitimate interests

DCMS proposes creating a list of legitimate interests for which no legitimate interest assessment would need to be conducted, as the legislation would recognize the processing purposes as always outweighing the interests of the individuals. The proposed list is relatively limited and uncontroversial and would reduce the burden of documentation obligations.

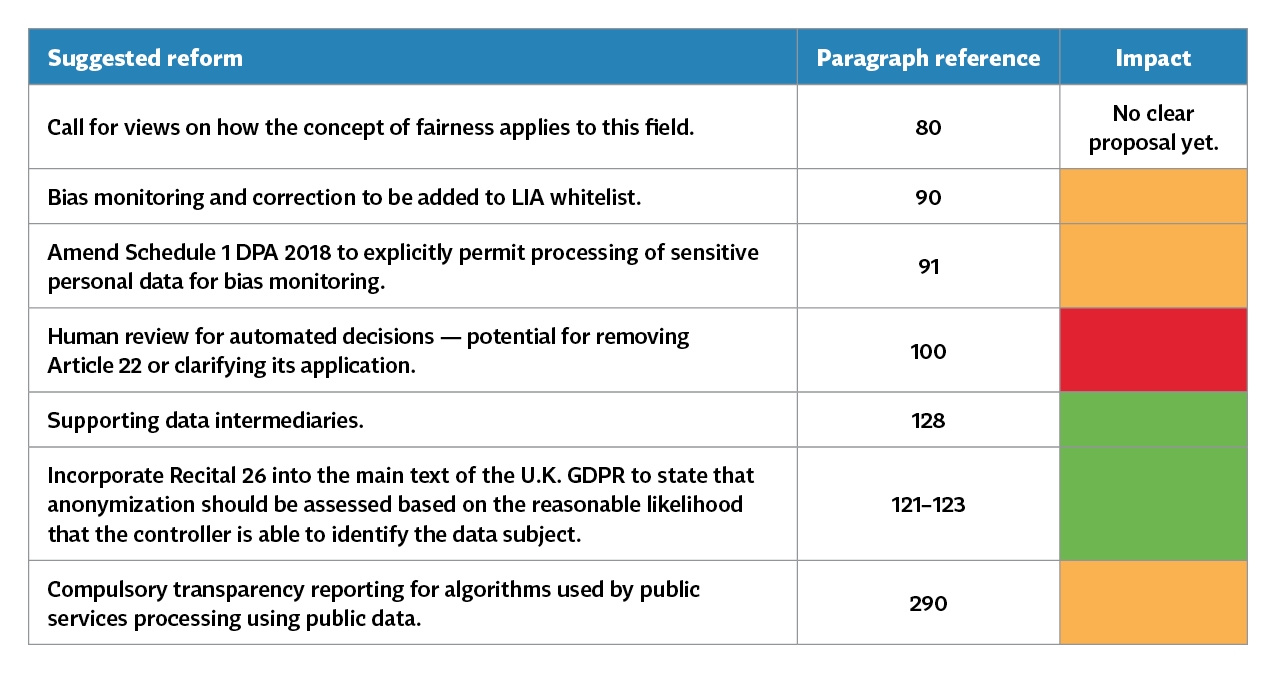

AI & machine learning

The consultation document notes that “currently, an AI practitioner needs to consider each use case individually and work out each time whether the data protection regime permits the activities.” Our view is that this statement not only holds true of any processing activity in any industry but is true of other legal considerations outside of data protection. The application of the law is always based on the relevant facts and consequentially, new projects will require new assessments of the law.

The proposal to reform the law to make the use of sensitive personal data for bias detection and correction easier is likely unnecessary. The existing framework under the U.K. GDPR and Data Protection Act permits this, and the ICO has already provided sector-specific guidance in this area.

The proposal to support the development and use of data intermediaries could be very beneficial to organizations sharing data for research and development purposes. Though the consultation document is very light on detail in this area, the proposal is welcome and could allow for innovative frameworks for data sharing within the existing data protection framework.

The proposal has an interesting discussion of algorithmic “fairness” — it postulates that determination of what is fair should be best left to sector-specific regulators rather than the ICO (79).

It also suggests clarifying when data will be regarded as “anonymous.” The suggestions to write Recital 26 into the text of U.K. GDPR seem to add little to current guidance from the ICO on this topic. More interestingly, DCMS suggests it may stipulate that anonymization should be assessed based on whether it is likely that the controller can identify the data subject. This would be a more permissive test than that set out in the GDPR, which requires one to consider the likelihood of identification by the controller or by another person (i.e., by anyone). In effect, this would be a return to the provisions of the Data Protection Act 1998. The proposal would help to clarify that if party A releases deidentified data to party B but retains the underlying identifiable data, the fact that party A could still identify individuals in the data would not automatically result in the data being personal in party B’s hands. Currently, if data is made accessible to the public at large (rather than a limited group of recipients), it is typical to require a higher standard of deidentification to achieve anonymization, as it is harder to assess the motives and means an unknown actor may have to identify the data. It is not clear how the proposal would protect individuals in this situation.

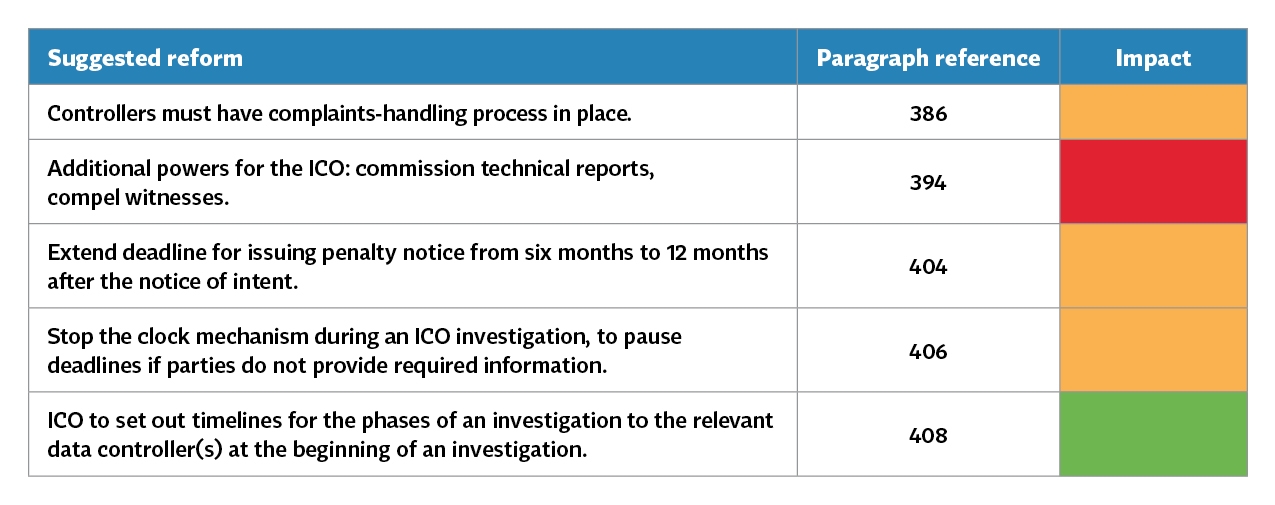

Reform of ICO

The amendments provide the ICO with stronger enforcement powers and will also change the timelines for enforcement action. The extension of the limitation period for investigations in particular will give the ICO more time to assess whether or not to issue a notice, potentially increasing the number of notices issued. The proposals are not disproportionate and are likely to have a beneficial impact on the regulatory environment in the U.K.

The reform also includes substantial amendments to the ICO’s internal governance and relationship with its sponsoring department, DCMS. These changes, if implemented, would have a big impact on the role and running of the ICO but we have not addressed them in detail in this document as they would not directly impact compliance obligations for data controllers and processors. Highlights of the proposed reforms are:

- The move away from a corporation sole (the Information Commissioner) to a more corporate model, where the commissioner would be the chair of the ICO with a separate CEO.

- ICO to take over the role of the Biometrics Commissioner and the Surveillance Camera Commissioner.

- A statutory framework that sets out the ICO’s strategic objectives (suggested as upholding data rights and encouraging trustworthy and responsible data use) and priorities.

- An express obligation to consider the desirability of promoting economic growth (already relevant under the Deregulation Act 2015), to consider the impact of its activities on competition and on public safety, and a statutory obligation to share data with some other regulators, including the CMA.

- ICO would have to adopt and report against key performance indicators (for those frustrated by delays to binding corporate rules approvals, perhaps this could be suggested?).

- Lessening the obligation on the ICO to deal with low-level complaints and for this to be replaced by an obligation on controllers to have published complaints policies and to to publish information on the number and type of complaints received.

The proposed changes would significantly change the U.K.’s data protection landscape. As we have discussed above, some of this would be welcome while other proposals are problematic or unclear. We encourage organizations to consider which areas of the proposal may be of relevance to them and engage with DCMS on those issues.

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash