Why benchmark? To arm yourself with valuable data

Contributors:

Mahmood Sher-Jan

CEO

RadarFirst

This article is part of an ongoing series on privacy program metrics and benchmarking for incident response management, brought to you by Radar, Inc., a provider of purpose-built decision support software designed to help privacy professionals perform consistent incident risk assessments and ensure timely notification, with real-time access to incident management reports and metrics. Find earlier installments of this serieshere.

“Why benchmark?” is a question we have revisited many times over the past year as we’ve been working on this article series. In a recent conversation with a data-driven privacy executive, I was reminded of the following quote from engineer, statistician and management consultant W. Edward Deming: “If you cannot measure it, you cannot improve it.”

Deming revolutionized quality process management, asserting, “If you can’t describe what you are doing as a process, you don’t know what you’re doing.” The idea is to measure and track your processes and use this data to improve.

Sounds simple enough, right? So why is this such a difficult undertaking in privacy? Part of the issue is the lack of established and reported privacy benchmark metrics to compare with. Without this data, privacy executives have long struggled to effectively articulate and justify their business impact and budgetary needs. Benchmark data can help privacy professionals and leaders overcome this challenge by providing an objective measure by which you can compare your privacy program’s performance against the industry’s practices and demonstrate where you are excelling and what areas need improvement. A data-driven approach to privacy is needed if privacy is to gain in importance and value within the corporate structure.

It is our intention with this ongoing article series to provide what privacy incident response metrics we can and comment as to trends, best practices, and notable takeaways we find in the benchmark data we report.

With that in mind, in advance of our upcoming panel presentation on this topic at IAPP Privacy. Security. Risk. 2018, I thought we could review some of our previously reported stats and take a look at what the latest incident metadata is telling us. We’ve pulled information gathered from a rolling 12-month date range that includes data as recent as July of 2018 in order to give us the most timely look at what is happening in the world of privacy incident response.

What percent of privacy incidents rise to the level of a notifiable data breach?

When looking at privacy program performance, this question seems to come up first: How many privacy incidents do we have, and how many of those incidents are data breaches requiring notification to affected individuals or regulators? This is a helpful metric over time as it directly contributes to risk mitigation and process-improvement opportunities. Getting a lot of incidents? Maybe it’s time to look for trends in recurring incident types and root causes and mitigate them if you can. Are you able to efficiently investigate, risk assess, and make timely notification decisions? Perhaps it’s time to explore process automation to streamline incident response to better handle the volume. Seeing a dip in the number of incidents internally reported? This might be a good opportunity to conduct trainings within your organization to reinforce what privacy incidents are and how they should be reported, to make sure you’re seeing everything that happens.

In anonymized Radar incident metadata from June 2017 to July 2018, we saw that over 13 percent of incidents rose to the level of a data breach. Unpacking that figure a bit, organizations with best practices in incident response are able to keep more than 86 percent of their incidents from becoming reportable by sufficiently mitigating risk and performing consistent and compliant multi-factor risk assessments to establish their burden of proof requirements and support their notification decisions. With appropriate risk mitigation and a documented, consistent, and automated risk assessment, these privacy professionals were able to avoid over-reporting incidents.

What category of incident is most prevalent?

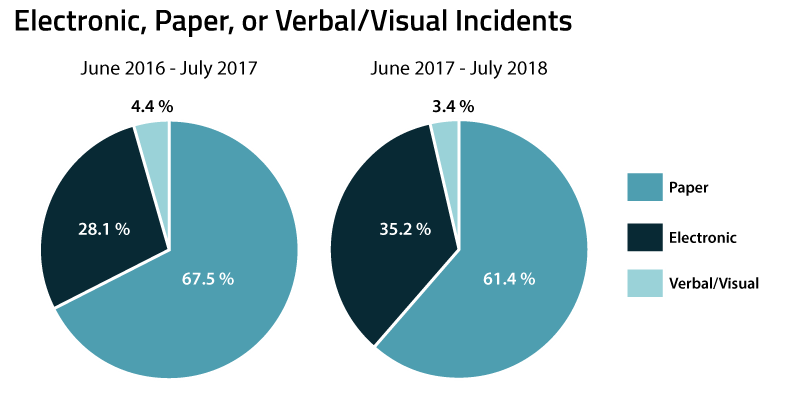

Earlier this year, we reported on the breakdown of incidents that involve electronic, paper or verbal/visual disclosures of records. Despite the coverage of massive hacking events in the news, the data showed that for incidents overall, paper incidents are far and away the most prevalent. In the newest data set, we see this trend continue.

Again, paper has remained the prevalent source of privacy incidents from July 2017 to July 2018. Interestingly, in a comparison against the previous time period (July 2016 to July 2017), we see that electronic incidents have seen a bit of an increase in terms of overall incident volume. We will continue to monitor this figure to see if this is an emerging trend.

So what does this continued prevalence of paper tell us that can help inform our privacy programs? That people are apt to make mistakes with paper and that electronic incidents may be easier to programmatically control through system processes and alerts. We all spend a good deal of time on electronic records and cybersecurity (rightly so), but we shouldn’t neglect paper. The reality is, our world today is still highly paper driven, and this is pervasive across industries.

Average detection, assessment, notification time frames

Measuring the average time frames for specific phases of the incident response lifecycle can provide valuable insights into your program and processes. Beyond meeting notification deadlines (as little as 72 hours under GDPR), this information can illustrate the efficacy of your training, indicate gaps in handoffs, and inform your budget and resources for the privacy program.

For this article, we revisited two time frames:

- The time it takes from the date an incident occurred to when it was discovered.

- The time from discovery date to providing notification to affected individuals.

In this more recent data set, we found that, on average, it takes 39 days to discover an incident and 25 additional days to then provide notification. Whenever you’re looking at data averages like this, it’s important to note the data points that are on either end of the average and could be skewing the data. The histogram below gives you a sense of how specific outliers impact this data set.

As you can see above, while it may take 25 days on average to provide notification on an incident once it is discovered, there is a larger trend of incidents that are risk assessed and notified within two weeks of discovery.

This data is interesting for a couple reasons. First, it demonstrates the way data can mislead if you aren’t willing to dig further. Look at the averages, by all means, but also know your program metrics well enough to get a sense of the data’s distribution and how to further dig into figures so that you can get to the root of what is happening. Secondly, and pertaining more to this specific time-frame data, these are important figures to track because it shows you where operational systems and procedures are working or lagging.

If you see long time frames between occurrence and discovery, that’s a good indication that your workforce needs more effective channel(s) and/or more real-time training to better identify and escalate privacy incidents. If you see a lag in how long an incident takes to assess and notify (from discovery date to notification), that time frame reflects what should be more within your control: your team managing incidents, documenting findings, assessing incidents and arriving at a breach decision. A lag could indicate the need for more resources, better risk assessment and automation, or both.

So ... why benchmark?

No one likes to make decisions in the dark. Arming yourself with data has great value. It provides confirmation of things working or a way to identify what areas may need your attention. Data helps you gauge the results of your incident-response program and to more effectively communicate those results to your executive team, board, and internal stakeholders. Data also helps us ensure we have the appropriate controls in place, that we’re looking at incidents the same way and that we’re all experiencing similar outcomes when applying similar processes.

In a way, benchmark data is also comforting in that there are guard rails. We’re all in this together and within the rails.

About the data used in this series: Information extracted from RADAR for purposes of statistical analysis is aggregated metadata that is not identifiable to any customer or data subject. RADAR ensures that the incident metadata we analyze is in compliance with the RADAR privacy statement,terms of useand customer agreements.