Florida Legislature's privacy law efforts fall short

Contributors:

Joe Duball

News Editor

IAPP

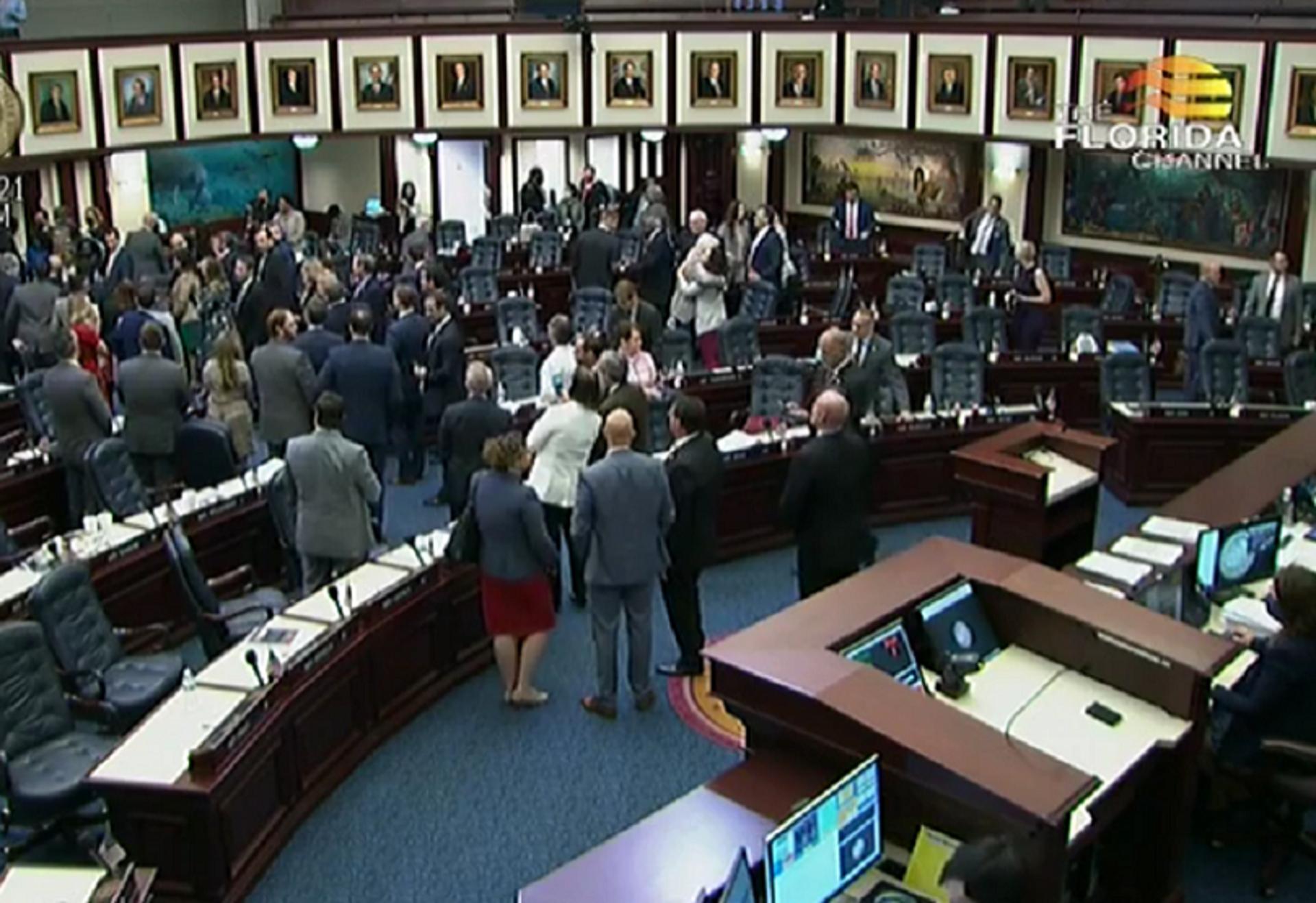

While many states have jumped aboard the trend of addressing privacy legislation during 2021 legislative sessions, all besides Virginia have fallen short to this point. That list of failures is now highlighted by a bizarre 24-hour stretch in the Florida Legislature, which was on the verge of making Florida the third U.S state to pass privacy legislation before the bill was nixed during the last day of the session.

Following votes to pass separate bills from the Florida House of Representatives and Senate in the week leading to the end of the session, the two chambers were unable to reconcile differences between bills, specifically issues over the inclusion of the private right of action.

"We started an important conversation about data privacy for Floridians and took strong first steps toward common-sense changes," said State Rep. Fiona McFarland, R-Fla., the House bill's sponsor. "Each session, there are dozens of important issues that we debate and consider in a short 60-day window. This is the nature of the legislative process, and I look forward to continuing the good work on this complicated issue in the next session."

The freshman lawmaker's comments somewhat downplay just how close the proposed Florida Privacy Protection Act was to becoming a law. After the House voted 118–1 to pass its version of the bill April 21, the State Senate passed an amended version of the House bill with a 29–11 vote the day before the conclusion of the legislative session. This meant the bill's fate would be decided by the House on the very last day it could, leaving somewhat of an "all-or-nothing" scenario.

The State Senate's most costly amendment to the House bill proved to be the removal of the private right of action, which State Sen. Jennifer Bradley, R-Fla., removed from her bill earlier in the session, while McFarland managed to pass her bill with the right of action intact. Shook, Hardy & Bacon Partner Al Saikali, CIPP/E, CIPP/US, CIPT, FIP, PLS, who provided testimony at various legislative committee hearings on the companion bills, indicated the House had intentions of putting the right of action back into the bill on deadline day, which would have required a vote in the House and Senate to pass the bill.

Instead, the House wrapped its final floor session without considering the amended bill from the Senate, presumably knowing its desire for the right of action would not be welcomed by the Senate upon the bill being sent back for a final vote before passage.

"I think roller coaster is a good phrasing," Saikali said. "I thought the better approach would've been to take what we can get now with the attorney general enforcing a law that has at least some of, if not more than, the consumer privacy rights of the California Consumer Privacy Act or (Virginia's Consumer Data Protection Act), then let's show people over a year or two that the attorney general enforcement tool is not enough by itself."

Seesawing with the private right of action

The arguments for and against a private right of action vary, with Saikali among those saying a right of action, as outlined by the House bill, would have been "all-encompassing" and brought a line of "frivolous lawsuits" from individuals seeking damages. Saikali was surprised the Senate's amended bill wasn't enough to get it passed given the provisions still favored hitting Big Tech companies hard, which is what Gov. Ron DeSantis, R-Fla., explained he wanted to do when publicly endorsing the Legislature's efforts.

"There are probably some of these lawsuits that have some merit, but when you file 1,100 class-action lawsuits in Illinois under (the Biometric Information Privacy Act) … you really create a risk that a law won't pass in another state because of the potential harm, particularly in a red state like Florida," Saikali said.

Former Florida Assistant Attorney General and Squire Patton Boggs Senior Associate Kyle Dull, CIPP/US, walked back the idea that the general concept of a private right of action is a complete drawback or weakens a law.

"Sometimes an attorney general's office has a limited amount of money," Dull said. "In my experience, someone would look at every complaint, but it might not be looked at for a while due to the resources. With the private right of action there, if the consumer thinks there is an issue, then they can always file their own lawsuit. And sometimes those cases end up resolving major issues. It's a mixed bag there."

Electronic Privacy Information Center Deputy Director Caitriona Fitzgerald is also of the mind that a private right of action would not be as damaging as it is being played up to be. What she sees as problematic is a law without a right of action that allows companies to simply "do a risk calculation" and understand attorney general enforcement against potential violations wouldn't hurt them.

"Industry just does a good job of selling the narrative that the private right of action would just be a win for plaintiff's attorneys," Fitzgerald said. "They just gloss over the fact that it would benefit consumers and that it has been proven in other states that it's the only way privacy rights get enforced because if states just pass a bill and give the attorney general enforcement authority with no additional appropriation, they may as well not pass anything."

Pros and cons of what would have been

Beyond the private right of action, other provisions of the proposed FPPA had similar types of hit-or-miss receptions from stakeholders and onlookers.

Former U.S. Federal Trade Commission Chief Technologist and White House Senior Adviser Ashkan Soltani said he was partial to the House bill because the Senate's final version appeared ineffective given what he deemed to be a set of vague definitions. Soltani's perspective is that some definitions might look fine to a lawmaker, but privacy professionals understand the potential loopholes set up by certain language.

"There was very clearly some language pushed in that tried to differentiate a transfer for advertising from a sale, essentially trying to weaken the definition of sale," said Soltani, who has previously done consulting work on the CCPA and the California Privacy Rights Act. "Combine that with the language around the definition of personal information, which requires that it be identifiable, essentially renders the law useless against the bulk of online tracking concerns that people have. Very little tracking is done by name."

Saikali thought the Senate's final bill was "still one of the most aggressive privacy laws in the U.S." He lauded a perceived balance the bill struck between consumer rights and foregoing coverage of a majority of small- and medium-sized enterprises.

"At the end of the day, this could be that middle-ground route that privacy advocates may start using in other red states," Saikali said. "I think there are some things that are a little different, like the general scope and the right to cure that's discretionary with the attorney general, but for the most part, it's taken from (the CCPA and CDPA)."

With his experience in the attorney general's office that would have been enforcing the law, Dull wasn't sure the rulemaking process for Florida's attorney general would have been very smooth given the law's effective date would have been July 1, 2022. He also wondered where the funding for enforcement would come from, noting while the office does have a dedicated data privacy unit, the law does not provide for additional financial support to stand up enforcement.

Dull did find a notable positive with how the bill addressed opting out of targeted advertising and profiling, noting the proposal was "broad and not limited in any way like it was in Virginia or open-ended like in California."

Debunking a compliance myth

The cost of complying with the proposed FPPA was brought up on several occasions by industry players and lawmakers throughout the legislative process. Arguments were focused on the astronomical financial toll compliance would have taken on a given business, pointing to figures out of California to plead their case, while there were also claims the proposed law would extend to SMEs that couldn't pay the compliance price.

Both claims are greatly exaggerated, according to Soltani, who indicated the California numbers are skewed and key factors on cost mitigation from current compliance efforts for other state and global privacy legislation have gone unmentioned.

"The reality is these thresholds don't affect the small 'mom and pop' stores that aren't selling personal information. Also, there are turnkey solutions … that let them comply with laws in the same way you would buy tax software to comply with the tax code," Soltani said. "These analyses also fail to recognize the revenue generated from privacy laws. We're already seeing in the innovation and privacy space that several companies are able to perform perhaps better advertising using less information. That kind of revenue is not calculated into these cost calculations. People only see the downsides."

How to approach 2022

With McFarland and Bradley indicating the privacy debate will pick back up in Florida's 2022 legislative session, it is fair to wonder where the conversation will start. A private right of action will undoubtedly be a sticking point, but Fitzgerald sees other considerations that could soften the discussion on that right.

"If it was a strong bill and maybe some appropriations were given to the attorney general or enforcement body, then that is a step in the right direction," Fitzgerald said. "A bill that puts real obligations on companies that are collecting and using data instead of putting the onus on consumers to opt out. Something with data minimization and requirements to delete after a period of time. That's a better step towards privacy."

Saikali opines the provisions of a 2022 bill might depend most on the leaders of Florida's two chambers, but he does expect a starting point to be the Senate's bill with the potential addition of a private right of action that could "get dialed back as it gets closer to the finish line."

Dull is of the mind that Florida's inaction certainly doesn't help push U.S. Congress to dig their heels in on addressing potential federal privacy legislation, which means 2022 could be another opportunity to change the narrative if it is done correctly.

"I think they could clarify some things about what kinds of businesses this applies to, which would make everyone happy," Dull said. "They can fix the threshold definition, the definition of what consent and personal information mean, and they could put some limiting factors on when someone can pursue a private right of action."

This content is eligible for Continuing Professional Education credits. Please self-submit according to CPE policy guidelines.

Submit for CPEs